Document 10868943

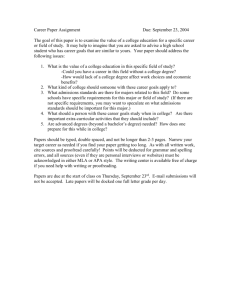

advertisement