Document 10868427

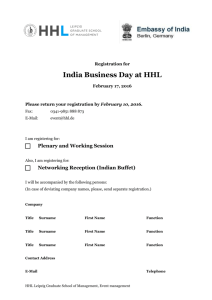

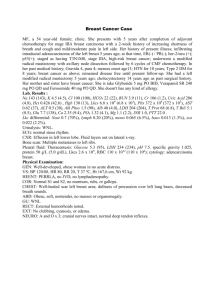

advertisement