Document 10868407

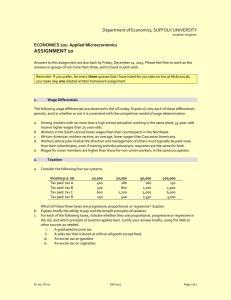

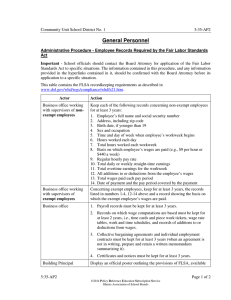

advertisement