Document 10868353

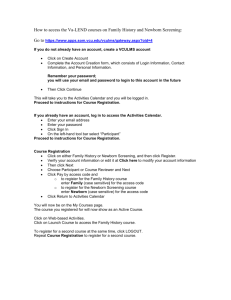

advertisement