Cancer Vaccines: A Look at the Hepatitis B and HPV...

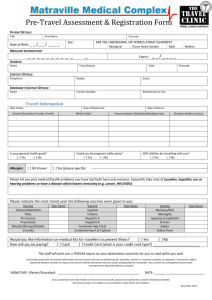

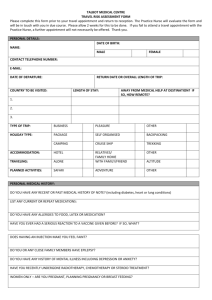

advertisement

Cancer Vaccines: A Look at the Hepatitis B and HPV Vaccines Allison N. Winnike, J.D. anwinnik@central.uh.edu For centuries mankind has searched for a cure for cancer and many therapies have been developed to treat this tissue nemesis. While survival rates have increased with these therapies, millions of people worldwide die each year from cancer, with one in eight deaths blamed on the disease. 1 As cancer research has progressed over the last few decades scientists have discovered that viruses cause a substantial percentage of cancers. A huge milestone in the search for a cure for cancer was reached in 1981 when the FDA approved the first cancer vaccine, a hepatitis B (HBV) vaccine which prevents primary liver cancer. Another milestone was reached 25 years later in 2006 when the FDA approved the second cancer vaccine, a human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to prevent cervical, vulvar and vaginal cancer and subsequently, in 2011, approved to prevent anal and throat cancer. One would imagine that these two cancer vaccines would receive universal praise and lead to great demand. On the contrary, the HPV vaccine in particular has been very controversial with many parents stating that they will not allow their children to receive the vaccine, which prevents at least five different types of cancer. Here we look at the history of both the hepatitis B and the HPV vaccines, comparing the regulatory approval timelines and vaccine recommendation guidelines. The hepatitis B virus, which is transmitted through infected blood and bodily fluids, is endemic in Asia and Africa. 2 Currently, approximately 2 billion people have already been infected and over half of the world’s population will have become infected with the virus in their lifetime. 34 The virus may stay dormant in the body for decades before any problems with the liver manifest. Hepatitis B causes primary cancer of the liver, also known as primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is one of the most common types of cancer worldwide. 5 Primary liver cancer is the third leading cause of death for men globally and is the seventh leading cause of death among women. 6 This cancer is particularly difficult to treat, with a five-year survival rate of only 10 percent. 7 1 nd Global Cancer Facts & Figures 2 Edition, AM. CANCER SOC’Y 1 (2011), http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-027766.pdf. 2 BARUCH S. BLUMBERG, HEPATITIS B: THE HUNT FOR A KILLER VIRUS 160 (2002). 3 Hepatitis B Fact sheet N°204, WHO, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/ (last modified Aug. 2008). 4 BARUCH S. BLUMBERG, HEPATITIS B: THE HUNT FOR A KILLER VIRUS 160 (2002). 5 Id. at 149. 6 Id. at 150. 7 Hepatitis B and Primary Liver Cancer, HEPATITIS B FOUNDATION, http://www.hepb.org/professionals/hepb_and_liver_cancer.htm (last visited Jan. 16, 2012). 2 Six years after the hepatitis B vaccine was developed in 1969, scientists discovered the link between hepatitis B and primary liver cancer in 1975 and suggested primary liver cancer could be prevented with a hepatitis B immunization. 8 Another six years later the FDA approved the Heptavax-B vaccine in 1981. 9 At the time Heptavax-B was approved primary liver cancer due to hepatitis B was not as common in the United States as it was in Asia and Africa, where hepatitis B is endemic and up to 50 percent of the population are carriers of the virus. 10 In 1981, liver cancer accounted for 20 to 40 percent of all cancers in these regions, whereas in the United States liver cancers accounted for only 2 percent of all cancers. 11,12 The FDA initially approved Heptavax-B only for a group of about 10 million Americans, including some health care workers, institutionalized mentally disabled, male homosexuals with multiple partners, and those with contacts with known carriers of the virus. 13 When the hepatitis B vaccine was approved in 1981, the FDA noted that the vaccine was only approved for use in high-risk individuals and not for the population at large and that those in high-risk groups had a 90 to 95 percent chance of avoiding the disease. 14 In 1982, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) published immunization guidelines which recommended the high-risk groups cited by the FDA receive the hepatitis B vaccine. Over the next decade only 2.5 million Americans received the hepatitis B vaccine, far short of the estimated 10 million in the high-risk group. ACIP noted that 80 percent of the immunized high-risk individuals were health care workers, but other high-risk groups, such as men who have sex with men, injection-drug users and heterosexuals with multiple partners were not being immunized. 15 By 1991, ACIP updated its recommendations to include universal childhood vaccination for hepatitis B in an effort to eliminate its transmission in the United States. 16,17 Because of this successful universal immunization program the number of new hepatitis B infections per year in the United States dropped from a 1987 high of 287,000 to 38,000 in 2009. 18 The second major milestone in cancer vaccine implementation occurred in 2006, when the FDA approved a HPV vaccine. This was an important new step in cancer prevention that could positively 8 BARUCH S. BLUMBERG, HEPATITIS B: THE HUNT FOR A KILLER VIRUS 154 (2002). Harold M. Schmeck Jr., Vaccine for Hepatitis B, Judged Highly Effective, Is Approved by F.D.A., N.Y. TIMES, Nov. 17, 1981, at C1. 10 Id. 11 Id. 12 Christopher Connell, New Vaccine Intended for 10 Million High-Risk Americans, ASSOCIATED PRESS, Nov. 16, 1981, available at http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uh.edu/hottopics/lnacademic. 13 Id. 14 Michael J. Conlin, FDA clears first hepatitis vaccine, UNITED PRESS INT’L, Nov. 16, 1981, available at 9 http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.lib.uh.edu/hottopics/lnacademic. 15 CDC, Achievements in Public Health: Hepatitis B Vaccination - United States, 1982-2002, 51(25) MMWR 549, 549550 (2002), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm5125.pdf. 16 CDC, Hepatitis B virus: a comprehensive strategy for eliminating transmission in the United States through universal childhood vaccination, 40(RR-13) MMWR (1991), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00033405.htm. 17 CDC, Achievements in Public Health: Hepatitis B Vaccination - United States, 1982-2002, 51(25) MMWR 549, 550 (2002), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm5125.pdf. 18 Disease Burden from Viral Hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States, CDC, http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/StatisticsHBV.htm (last visited Jan. 16, 2012). 3 affect the majority of the population. At the time the hepatitis B vaccine was approved, relatively few Americans were infected with hepatitis B. Conversely, HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) and 80 to 90 percent of the sexually active population will be infected with it at some point in their lifetime. 19 HPV has many strains and causes several deadly cancers, including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, penile, anal, and oropharyngeal cancer (OPC), a type of throat cancer. 20 It is spread through sexual contact and like hepatitis B, can lie dormant for decades before any cancer develops. 21 In the United States, HPV causes approximately 22,000 new cases of cancer each year (about 15,000 in females and 7,000 in males). 22 Globally, cervical cancer is the second leading cause of cancer in women. 23 The first HPV vaccine approved in 2006, Gardasil, is a quadrivalent vaccine which prevents HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. 24,25 Gardasil was originally approved for use in females ages 9 to 26 to prevent cervical cancer and genital warts. 26 In 2009, FDA approved another HPV vaccine, Cervarix, a bivalent vaccine which prevents HPV types 16 and 18, for use in females ages 10 to 25 to prevent cervical cancer. 27,28 The year after FDA approval of Gardasil ACIP issued recommendations for a cohort which mirrored the female group for which FDA approved the vaccine. In these 2007 ACIP recommendations females ages 11 to 12 years were the primary vaccination target, but the guidelines allowed for vaccine administration as young as age 9 and as old as age 26 for catch-up vaccination. 29 While some parents were eager to have their children vaccinated, there was a public backlash against the recommendations with many parents refusing to allow their children to be immunized because they believe the vaccine encourages sexual promiscuity. 30 In 2007, Texas Governor Rick Perry issued an Executive Order 19 Karin B. Michael & Harald zur Hausen, HPV vaccine for all, 374 LANCET 268, 269 (2009). Genital HPV Infection - Fact Sheet, CDC, http://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm (last visited Jan. 16, 2012). 21 Id. 22 Gardiner Harris, Panel Endorses HPV Vaccine for Boys of 11, N.Y. TIMES, Oct. 25, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/26/health/policy/26vaccine.html. 23 Human papillomavirus (HPV), WHO, http://www.who.int/nuvi/hpv/en/ (last modified Oct. 2011). 24 June 8, 2006 Approval Letter - Human Papillomavirus Quadrivalent (Types 6, 11, 16, 18) Vaccine, Recombinant, FDA to Merck, available at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm111283.htm. 25 FDA Licenses New Vaccine for Prevention of Cervical Cancer and Other Diseases in Females Caused by Human Papillomavirus, FDA, June 8, 2006, available at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2006/ucm108666.htm. 26 June 8, 2006 Approval Letter - Human Papillomavirus Quadrivalent (Types 6, 11, 16, 18) Vaccine, Recombinant, FDA to Merck, available at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm111283.htm. 27 October 16, 2009 Approval Letter – Cervarix, FDA to GSK, available at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm186959.htm. 28 FDA Approves New Vaccine for Prevention of Cervical Cancer, FDA, Oct. 16, 2009, available at http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm187048.htm. 29 CDC, Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 56(RR02) MMWR (2007), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5602a1.htm. 30 Dan Eggen, Rick Perry backs away from HPV vaccine decision during presidential run, WASH. POST, Aug. 16, 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/rick-perry-reverses-himself-calls-hpv-vaccine-mandate-amistake/2011/08/16/gIQAM2azJJ_story.html (last updated Sept. 13, 2011). 20 4 requiring HPV immunization for females entering the sixth grade, but angry Texas legislators overrode the order and passed a law stating that immunization against HPV will not be required for any elementary or secondary school student. 31,32 During the 2012 Presidential campaign Rick Perry was often criticized by his Republican primary rivals for supporting HPV vaccination in the past. 33 The resistance to HPV vaccines reaches beyond the political arena with only 32 percent of recommended females receiving the three dose series of the vaccine. 34 Despite a cool public reception to the HPV vaccines, medical research on the virus continues. Research has shown that these vaccines prevent more than just cervical cancer and the FDA has expanded approval for vaccine use to prevent other cancers. In 2008, FDA approved Gardasil for prevention of vulvar and vaginal cancer. 35,36 The next year Gardasil received FDA approval for use in males ages 9 to 26 for prevention of genital warts. 37,38 In 2010, the FDA approved Gardasil for prevention of anal cancer in both sexes. 39,40 Recently ACIP has updated its immunization recommendations to reflect these new uses. In 2011, ACIP published recommendations that males age 11 to 12 be immunized against HPV-16 and HPV-18 to prevent anal, penile and throat cancers. 41 The recommendations allow for catch-up vaccination administration in males ages 9 to 21 years. 42 Once ACIP recommended universal childhood immunization, infant hepatitis B vaccination rates increased from 16 percent in 1993 to 90 percent by 2000. 43,44 HPV vaccination remains low among 31 Tex. Exec. Order RP65 (Feb. 2, 2007), available at http://governor.state.tx.us/news/executive-order/3455/. th H.B. 1098, Leg., 80 Reg. Sess. (Tex. 2007), available at http://www.legis.state.tx.us/tlodocs/80R/billtext/pdf/HB01098F.pdf. 33 Dan Eggen, Rick Perry backs away from HPV vaccine decision during presidential run, WASH. POST, Aug. 16, 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/rick-perry-reverses-himself-calls-hpv-vaccine-mandate-amistake/2011/08/16/gIQAM2azJJ_story.html (last updated Sept. 13, 2011). 34 CDC, Recommendations on the Use of Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in Males — Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011, 60(50) MMWR 1705, 1705 (2011), http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6050.pdf. 35 September 12, 2008 Approval Letter – Gardasil, FDA to Merck, available at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm111270.htm. 36 FDA Approves Expanded Uses for Gardasil to Include Preventing Certain Vulvar and Vaginal Cancers, FDA, Sept. 12, 2008, available at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2008/ucm116945.htm. 37 October 16, 2009 Approval Letter – Gardasil, FDA to Merck, available at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm186991.htm. 38 FDA Approves New Indication for Gardasil to Prevent Genital Warts in Men and Boys, FDA, Oct. 16, 2009, available at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm187003.htm. 39 December 22, 2010 Approval Letter – Gardasil, FDA to Merck, available at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm238074.htm. 40 FDA: Gardasil approved to prevent anal cancer, FDA, Dec. 22, 2010, available at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2010/ucm237941.htm. 41 CDC, Recommendations on the Use of Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in Males — Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011, 60(50) MMWR 1705, 1705 (2011), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6050.pdf. 42 Id. 43 CDC, Achievements in Public Health: Hepatitis B Vaccination - United States, 1982-2002, 51(25) MMWR 549, 550 (2002), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm5125.pdf. 32 5 females and extremely low among males. 45 It remains to be seen whether new recommendations that all 11 to 12 year olds receive immunization against HPV will translate to similar high compliance rates analogous to the hepatitis B timeline. Health Law Perspectives (March 2012) Health Law & Policy Institute University of Houston Law Center http://www.law.uh.edu/healthlaw/perspectives/homepage.asp The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the various Health Law Perspectives authors on this web site do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs, viewpoints, or official policies of the Health Law & Policy Institute and do not constitute legal advice. The Health Law & Policy Institute is part of the University of Houston Law Center. It is guided by an advisory board consisting of leading academicians, health law practitioners, representatives of area institutions, and public officials. A primary mission of the Institute is to provide policy analysis for members of the Texas Legislature and health and human service agencies in state government. 44 CDC, A Comprehensive Immunization Strategy to Eliminate Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States - Part 1: Immunization of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 54(RR-16) MMWR 1, 2 (2005), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5416.pdf. 45 CDC, Recommendations on the Use of Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in Males — Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011, 60(50) MMWR 1705, 1705 (2011), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6050.pdf.