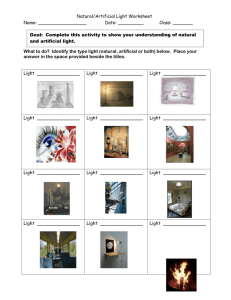

I

advertisement