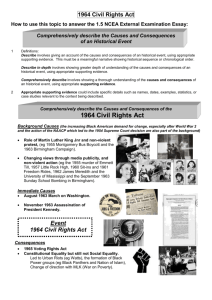

. ...................

advertisement