Document 10859607

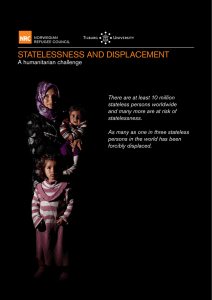

advertisement