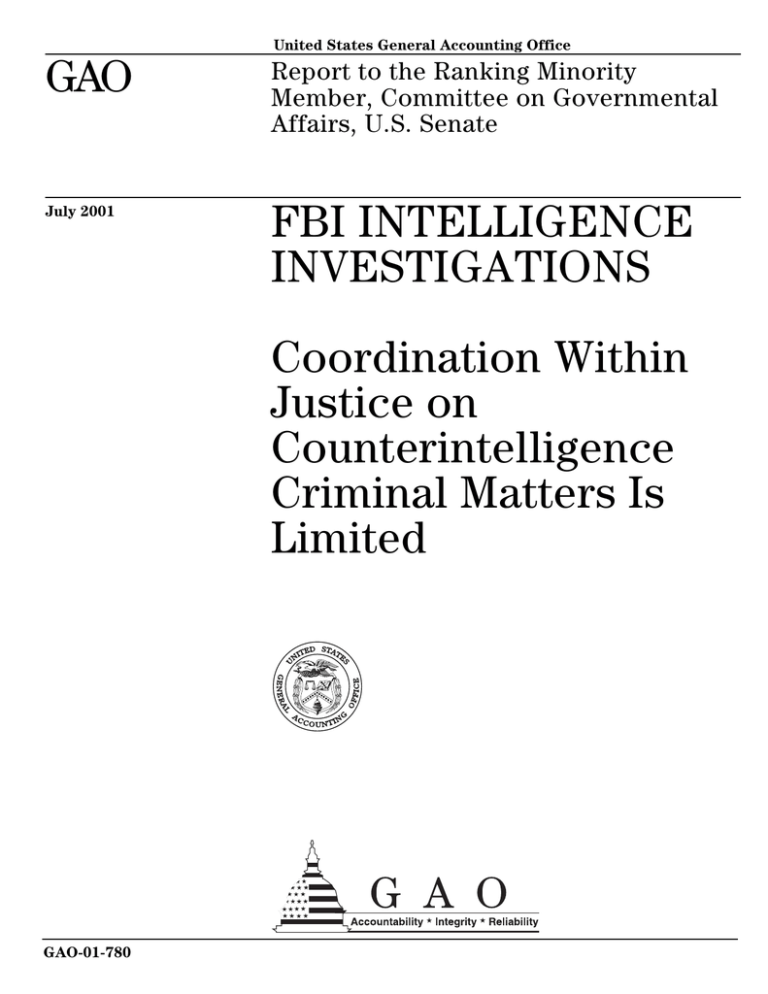

GAO FBI INTELLIGENCE INVESTIGATIONS Coordination Within

advertisement