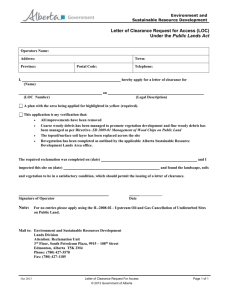

GAO PERSONNEL SECURITY CLEARANCES

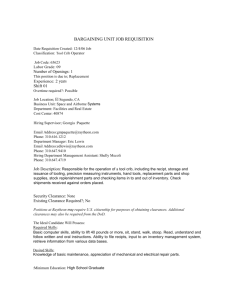

advertisement