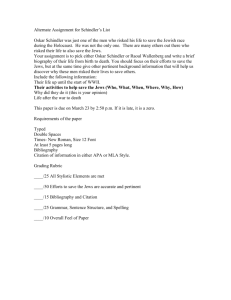

RUDOLPH M. SCHINDLER AND 1976 1981

advertisement