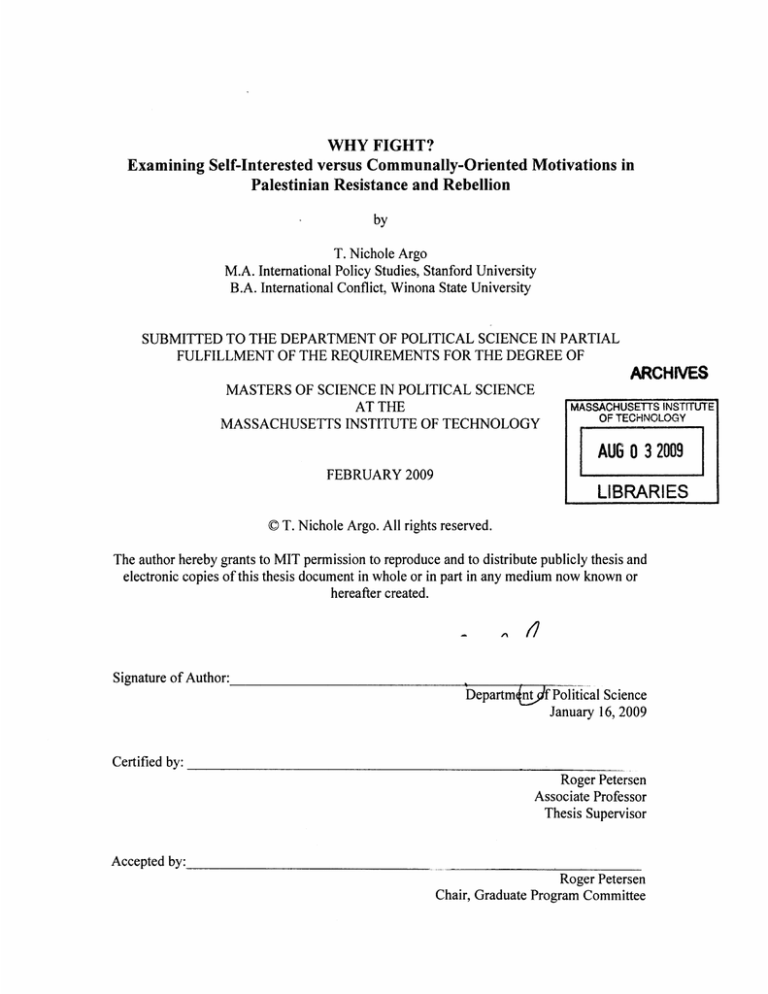

Examining Self-Interested versus Communally-Oriented Motivations ... WHY FIGHT? Palestinian Resistance and Rebellion

advertisement