The Press of a People: The Evolution ... Changing Political Community

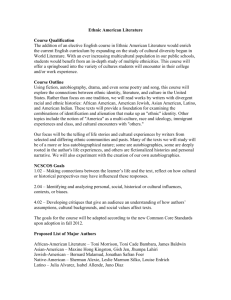

advertisement