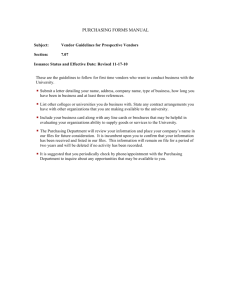

of A Matter Understanding Sagree Sharma

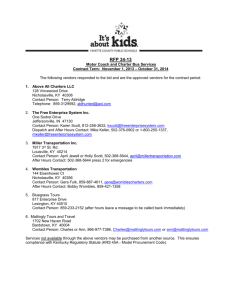

advertisement