Saving the York Avenue Estate: Meghan J. Boyce

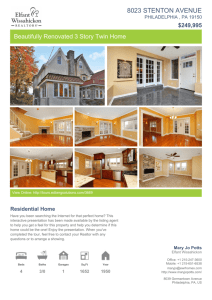

advertisement