Mobile Technology – A Strategy for RtI It’s about Equity

advertisement

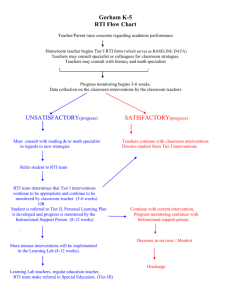

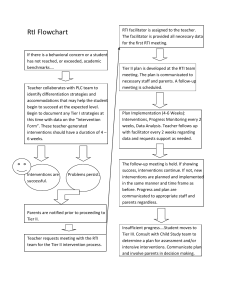

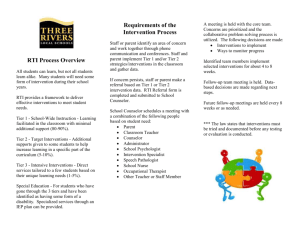

Mobile Technology – A Strategy for RtI It’s about Equity by: Tracey L. McCully It is widely accepted that children learn at different rates. Some students understand a concept at first presentation; other learners need to practice the skill or concept many times over. “... every child is an individual and individuals exhibit differences in growth due to many factors...,” say Fisher and Frey, 2010. today’s average student has played 10,000 hours of video games and sent 250,000 emails. They have talked for 10,000 hours on the phone. Most have watched 20,000 hours of TV and viewed 500,000 commercials. School occupied less than 9,000 hours of their time, and they read for fewer than 4,000 hours. Educators believe all students should have access to rigorous and relevant curriculum. “Too often, lower achieving students are relegated to a steady, curricular diet of low-level skill drills and rote learning of facts.” (Tomlinson and McTighe, p. 85) Often students needing more time to learn, practice rote skills and are not encouraged to access the interesting, motivating rigorous work of their classmates. Since their youngest years, children’s brains were bombarded by digital input. They learned that screens are to be manipulated and interacted with rather than passively consumed (Jukes, p 3). They access, consume, process and use information and communicate with the world far differently than most of us. Metaphorically, low-achieving students practice the drills in isolation many times over with no opportunity to combine drills, rules, and relationships to play the real game. Tomlinson and McTighe (p. 68), remind, “Both drills and authentic application are necessary in the classroom. Students need to master the basics, and skill drills support that need. But learners also need a chance to use their knowledge and skills--in other words, to “do” the subject.” They further state, “Virtually all students should consistently experience curricula rooted in the important ideas of a discipline that require them to make meaning of information at higher levels” and “...meaning-driven, thought-based, application-focused curriculum cannot be reserved for only a small proportion of learners.” (Tomlinson and McTighe; p. 84) Twenty-first century learners are bombarded with so much technological stimuli; their brains are different than brains of other generations. Ian Jukes (p. 21) reports that by the age of 21, Humans are born with about 50% of their brains’ wiring in place allowing us to accomplish critical survival functions like respiration and circulation. The other 50% of our brains’ connections develop after birth. (Jukes, McCain, Crockett; p. 12) It was thought a child’s brain was established by three years old, and the brain wouldn’t change much thereafter. New scanning technologies, however, show the human brain is highly adaptive and malleable throughout life. Brain cells constantly die off and are replenished. Depending on the input or experiences we have and the intensity and duration of those experiences, our brains reorganize and adapt. Underutilized neural pathways die off while heavily activated pathways are coated with myelin, a fatty substance that speeds the transmission of signals in the brain. The connections most used develop into complex, highspeed neural networks. (Jukes, McCain, Crockett; p. 13) Constant exposure to technology contributes to the fact that today’s children are more difficult to engage at school. Educators know that engagement and motivation are critical for learning. Without motivation, there is no learning; a teacher must instill the desire to learn in his or her students. their own connections. “Digital Natives” want learning that is relevant, active, instantly useful and fun while teachers are compelled to cover the curriculum. (Jukes, 2008, p. 2) With the immense gap between students’ digital and learning preferences and styles and education’s non-digital teaching practices, huge numbers of students are dropping out of school. (Jukes, 2008, pp. 6, 7) Our schools were not designed for the children of the 21st century, and these children are not the students today’s teachers were trained to Self-Correcting teach. (21st Century Our students have access to the newest technologies at home; so also do they need access to the newest technologies at school. iPods, iPads, and other mobile devices can be loaded with a multitude of applications that allow students to practice basic skills in an engaged, fun manner. Students can develop basic skills while solving rigorVarious Levels of Play ous, real-world problems that make learning meaningful and motivating. Students who need to practice basic skills no longer need to participate in a dumbed-down Engaging curriculum while developing basic skill fluencies. Fluency Project, 2010) Due to digital bombardment, most learners are visual or kinesthetic learners rather than the auditory learners Various Ways to Play more familiar to teachers. Their eyes move across a page of print much like their eyes scan a video game, virtually ignoring the right side and bottom of a page. The colors stimulating their brains are different, too. While adults are accustomed to black print on a white page, 21st century learners prefer blue or black backgrounds and bold red, pink, neon green or burnt orange text. (Jukes, p. 21) Because brains are neurologically different, our classrooms must be different. Their brains process information in a parallel or simultaneous manner. They prefer to work in groups rather than independently and crave the instant gratification of pushing a button and seeing a response. Today’s student likes to learn what he or she needs at the moment (“just-in-time learning”) while we teach “just-in-case” that knowledge is needed for an exam or for a career in the future. Linear, sequential learning is boring to students who prefer random access to information from which they make Response to Intervention, or RtI, is a perfect venue for using mobile technology to provide practice to students needing more time to develop grade-level skills. RtI is a framework for providing a student with what he or she needs instructionally, when he or she needs it, and for only as long as he or she needs it. The student continues to engage with the instructional core. A maxim in special education states equity is giving each student what he or she needs to learn to his/her potential. Fisher and Frey (p. 1) explain, “This Response to Intervention (RtI) system is designed to change learner performance as a function of targeted instruction. The use of an RtI model is desperately needed to ensure that equal access to learning is available for every child.” Response to Intervention (RtI) is a systematic, data-driven approach to instruction that benefits every student. RtI is meant to provide a full con- tinuum of instruction, from the general core to supplemental or intensive levels--instruction to meet the academic and behavioral needs of students. RtI integrates resources from general education, categorical programs, and special education through a comprehensive system of core instruction and intervention. The goal is to meet the learning needs of each student to reach high expectations, ensuring equity of access to a quality public education for all students. (O’Connell, 2008) The core components of RtI include: • high-quality classroom instruction • research-based instruction • universal screening • continuous classroom progress monitoring • research-based interventions • progress monitoring during instruction and interventions • fidelity of program implementation • staff development and collaboration • parent involvement (O’Connell, 2008) Response to Intervention is a comprehensive, school-wide process of early intervention and prevention of academic and behavioral difficulties. It is a process that utilizes all resources within a school in a collaborative manner to create a single, well-integrated system of instruction and interventions informed by student outcome data. Positive outcomes for all students are a shared responsibility of all staff members. RtI is a multistep process of providing high-quality, research-based instruction and interventions at varying levels of intensity for students who struggle with academics or behavior. The interventions are matched to student need, and progress is closely monitored at each level of intervention to make decisions about further instruction or intervention or both. RtI is not a program but rather a framework or process collaboratively identified by each school or district to meet the needs of ALL students. RtI is typically a three-tiered intervention model that starts with and emphasizes instruction and intervention in the general education classroom. Schools identify at-risk students, regularly monitor student learning, provide research-based, and utilize a systematic approach to ensuring academic success for all students. (Academic and Behavior Triangle; Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education) Tier One focuses on preventing learning difficulties and providing the best first instruction of all students. It is the primary academic program available for all students with a focus on best first instruction, common assessments, and data analysis within grade levels or departments. Tier One instruction meets the needs of 80% of the students. Mobile technology with supplemental, educational applications is used as practice and motivation for students. Tier Two interventions are designed to meet the needs of students who are one or two years below grade level, near 15% of a grade level’s students. Tier Two is an additional opportunity for students to learn missing prerequisite skills required to master grade level standards. Most Tier Two interventions last three to eight weeks with multiple data monitoring points throughout the intervention. Student’s response to these interventions is monitored closely to determine if additional interventions are needed. Students continue learning the core curriculum in Tier Two. Mobile technology with apps chosen to specifically meet a student’s current need is an appropriate Tier Two intervention. Tier Three intervention is designed to meet the needs of students requiring intensive intervention: students are usually more than two years below grade level. Students at this level are seriously at-risk as indicated by extreme and chronic poor performance. Intensive interventions are instituted when a student is not responding to Tier One and Tier Two interventions and will be best served by providing more intensive interventions or placement in alternative instructional materials rather than the core curriculum. ments for students needing more time and practice after best-first instruction. Fischer and Frey (2010, p. 15) state, “A core assumption of RtI is that all students can reach high levels of achievement if the system is willing (and able) to vary the amount of time students have to learn and the type of instruction they receive.” Mobile applications are a good solution for providing the skills practice students’ need in an engaging manner. Collins, Allan & Halverson, Richard; Rethinking Education in the Age of Technology — The Digital Revolution in the Age of Technology; Teachers College Press; 2009. “It is difficult to overstate the value of practice. For a new skill to become automatic or for new knowledge to become long-lasting, sustained practice, beyond the point of mastery, is necessary.” (McEwan-Adkin, p. 29) And, some students need more practice than others. Practice in a fun environment is what today’s learners crave. To help all students learn at high levels, we must first believe they can learn at high levels. Then we must explicitly teach students at high levels giving each the time and practice needed while simultaneously engaging all students in rigorous, relevant problem solving. “With appropriate instruction and intervention, virtually every student is capable of learning challenging content.” (Fisher and Frey, p.2) Technology, particularly mobile technology, is a cost-effective, engaging way to build the academic skills students need. Students will practice and develop fluency in basic skills while simultaneously involved with high-level problem solving with their peers. All students will have the time and materials to learn what they “need”. e Skills Learning creates software for iPods and iPads, technologies today’s students are so familiar with. Minimods are designed for practice in building automatic or fluent skills in reading, language arts and mathematics. e Skills’ Minimods provide perfect Tier 1, Tier 2, or Tier 3 learning enhance- REFERENCES 21st Century Fluency Project; Understanding the Digital Generation; Keynote Presentation; 2010. Brooks-Young, Susan; Teaching with the Tools Kids Really Use; Corwin; 2010. Fischer, Douglas & Frey, Nancy; Enhancing RtI — How to Ensure Success with Effective Classroom Instruction and Intervention; ASCD; 2010. Jukes, Ian; Understanding Digital Kids: Technology and Learning In the New Digital Landscape; The InfoSavvy Group; May, 2008. Jukes, Ian; Closing the Digital Divide: 7 Things Education & Educators Need to Do; e; The InfoSavvy Group; Prepared for the Teacher Mass Lecture; Singapore; Sept. 2006. Jukes, Ian, McCain Ted, Crockett, Lee; Understanding the Digital Generation — Teachingand Learning in the New Digital Landscape; Corwin; 2010. McEwan-Adkin, Elaine K.; 49 Reading Intervention Strategies for K-6 Students — Research-Based Support for RtI; Solution Tree; 2010; p. 29. Missouri Department of Education and Secondary Education; Academic and Behavior Triangle (PDF); Dec. 2010; dese.mo.gov. O’Connell, Jack; Response to Instruction and Intervention, memo to County, District, and Charter Superintendents; California Department of Education; Nov. 14, 2008. Rosen, Larry; Rewired — Understanding the iGeneration and the Way They Learn; Palgrave Macmillan; 2010. Sprenger, Marilee; Brain-Based Teaching in the Digital Age; ASCD; 2010. Sylwester, Robert; A Celebration of Neurons — An Educator’s Guide to the Human Brain; ASCD; 1995. Tomlinson, Carol Ann & McTighe, Jay; Integrating Differentiated Instruction & Understanding by Design: Connecting Content and Kids; ASCD; 2006. This Mobile Application Selection Rubric is helpful in evaluating mobile apps for schools. About the Author In 22 years of teaching, Tracey has taught preschool through college students in California. Most of her teaching was devoted to children with learning disabilities. Tracey provided individualized direct instruction and skill-building for children in kindergarten through eighth grades. Besides her teaching experience, she has served in a number of leadership and administrative positions at the site, district, and county levels. She currently works at a California County Office of Education in the Curriculum and Instruction department. Tracey’s responsibilities range from managing categorical programs for several school districts, to implementing Professional Learning Communities, to coaching instructional strategies for teachers working with the county’s most at-risk high school student population. Tracey’s education includes a BA in Child Development from the University of California, Davis and Masters Degrees in Education in both learning handicaps and administration from Fresno Pacific University. For more information about e Skills Learning and new iPod/Pad apps for the classroom PO Box 639 53 Rutherford Road Candler, NC 28715 Toll Free Phone (800) 638-6470 Toll Free Fax (800) 638-6499 Visit Us on the Web www.eskillslearning.net eskillslearning