Religions, Human Capital and Earning in Canada Abstract Maryam Dilmaghani

advertisement

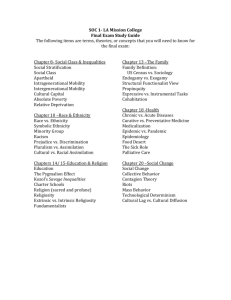

Religions, Human Capital and Earning in Canada Maryam Dilmaghani McGill University, Department of Economics, CRIEQ and CIRANO Abstract Using Ethnic Diversity Survey (EDS) I examine how religious belief and practice relate to earning in Canada. Besides the cross-religion differences in earning I also account for overall religiosity using a composite scored-based variable constructed by means of several questions in the survey. A negative correlation between religiosity and earnings is found controlling for demographic and human capital variables. The difference between earning and human capital return of different religions are economically and statistically significant where Jews enjoy a premium and Muslims’ earnings are significantly lower than average Canadian. The most plausible explanation of this discrepancy seems to be the return to experience. Keywords: religiosity, earning JEL Classification: Z12 Correspondence to the author: maryam.esmaeilpourdilmaghani@mail.mcgill.ca I. Introduction Although the relationship between religiosity and labour market outcomes seems of interest to labour economists, social economists and economic demographers it is remarkable that the last study of this issue using Canadian data dates back to around 25 years ago (Tomes, 1983, 1984 and 1985; Meng and Sentence 1984). This paper’s objective is to fill this gap by examining the question of labour market impact of religions and religiosity in Canada. This study is carried out using Ethnic Diversity Survey and its detailed data on religious affiliations, the extent of religious belief and the frequency of religious practice along other relevant socioeconomic factors. The conception of the question is twofold: not only I consider religiosity per se defined as commitment to a religion and its tenets (with no distinction among religions) and its relationship with earning but also I examine earning and human capital return differentials among a number of religious denominations present in Canada. Before going any further an introductory note reviewing recent economic literature on this matter is in order. Religion is susceptible of impacting economic outcomes both through institutions and by way of affecting individual agents’ incentives and behaviours. The institutional channel is more suitable for historical studies (see: Dudley and Blum 2001; Boppart et al. 2008) or for researches focusing on the countries in which the secularisation of institutions is still weak (see: Guiso et al. 2003). However the channel of individual behaviour and incentives seems to be universally as relevant as in the past. I believe one way of making a distinction among various parts of empirical literature on the economic impact of religion is to distinguish between macro-data and micro-data studies. The literature using micro-data itself can be divided into two categories based on whether the economic impact of overall religiosity has been examined or the crossreligion differences in economic attainment were the subject matter of the research. On the macroeconomics side McCleary and Barro (2003) examined the relationship between economic growth and religion in a cross-section of countries through time. They could show that while a country’s average religious belief is positively related to economic growth the frequency of religious practice relates to economic growth through a negative coefficient. Durlauf and colleagues (2006) made a critical review of the results obtained by Barro and MacCleary through which they deduced that their finding may not be robust to the specification’s modifications. Within micro-data literature the impact of overall religiosity on a wide array of outcomes such as educational attainment (Sander 2001; Saucerdote and Glaeser 2001; Blusch 2007), female labour force participation and fertility (see for a review: Lehrer 2008), tendency towards entrepreneurship (e.g. Audretsch et al. 2007) and alike has been examined. Focusing on data from the US the stylized facts derived from these studies can be summarized as follows. Education is generally a positive predictor of religiosity; income is a strong, positive predictor of religious contributions, but a very weak predictor of most other measures of religious activity, such as church attendance and frequency of prayer. More importantly than income however age, gender, and religious upbringing predicts religious involvement (see also: Azzi and Ehrenberg 1975; Ehrenberg 1977, Long and Settle 1977; Ulbrich and Wallace 1983 and 1984, and Biddle 1992). Finally the studies that look at cross-religion differences in earning and human capital return resulted in the finding of superior earning and educational attainment of Jews compared to the rest of population in the US and in Canada (see: Steen 1996; Chiswick 1983 and 1985; Chiswick and Huang 2006; Meng and Sentence 1984; Tomes 1983, 1984 and 1985). Meng and Sentence, using data from Canadian National Mobility Study 1973, found that there is indeed a statistically significant difference among the earning of the devotees’ of various religions as well as their human capital return; mainly they found that all others equal Jews earn more than Catholics and Protestants. However the results reported by Tomes, using 1971 Canadian Census, shed some doubts on the robustness of Meng and Sentence’s results for he found a much smaller gap between Jewish earning and the rest of the population. This paper aims at covering both questions of economic impact of religiosity as well as cross-religion differentials in earning and human capital return. In the first part of the paper I consider religiosity as a continuous variable by construction of a score-based religiosity index through a combination of several questions of the survey. The objective is to see to what extent religiosity as an observable and measurable trait can predict labour market outcomes. I also discuss the possible behavioural impacts of religion that can serve as a mechanism linking religiosity and labour market attainment such as honesty, trustworthiness, and discipline previously put forward by researchers. In the next part I compare labour market attainment of Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, individuals self-reporting with no religious affiliations and the residual group. The reminder of paper is organized as follows. The next section is devoted to the presentation of the dataset, the construction the Consolidated Religiosity Index (CRI) and econometric methodology. In the third section I examine the impact of overall religiosity (measured using CRI) by including it in an earning human capital function. And the forth section deals with cross-religion differentials in earning and human capital return. The concluding remarks are included in the last section. II. Data and Methodology The dataset used in this study is Ethnic Diversity Survey (EDS) of Statistic Canada conducted between April and August 2002 and released in 2005. The dataset is a survey of 41695 respondents of 15 years old and above male or female legal residents of Canada including, besides Canadian nationals and permanent residents, people from another country sojourning in Canada on employment or student authorizations, Minister's permits as well as refugee claimants, and any family member living with them (see EDS Guide, page72). The survey incorporates more than 300 variables. There is precise information about religious affiliation and ethnic background of the respondents covering several generations. The advantage of this survey to labour market surveys is in that it contains specific information about the self-reported importance of religion and the frequency of religious practice. This feature makes it possible to treat religiosity as a quantitative variable regardless of the denomination and in fact such conception constitutes the subject matter of the next section of this paper. The education measured by the highest degree attained by the respondent as well as that of their parents and their spouses (if applicable) is surveyed. The hours worked per week as well as annual personal income and annual household income of the respondents are included in the survey. Although the survey’s information is on income rather than earning it is been possible to know the source of the reported income. As such in order to estimate the standard human capital earning function (at times abbreviated by HCEF in this paper) I could exclude the respondents whose reported incomes were from sources other than employment or self-employment (see EDS Guide, page-298). In addition the dataset provides various interesting information such as ethnic background up to several generations, the linguistic proficiency of the respondents, the sector of professional activity, the structure of social network and family ties, trust and social attitude and alike which enabled me to augment the human capital earning function by extra control variables. I briefly report some descriptive statistics with regard to religions and religiosity in Canada according to the data from EDS. Note that unless otherwise is indicated all reported statistics are weighted by survey’s weights. In Canada self-reported Catholics constitute 41.52% of sample followed by Protestants with 27.19% and by the respondents with no religious affiliation (including atheists but not limited to it1; abbreviated by NRA hereafter) with 16.23%. Among the minority 1 Note that it may be difficult to distinguish between sects and groups of philosophical thoughts and some religions in the absence of a clear definition of religion. The variable NRA defined in the Table-2 explains how this distinction is made in the EDS. It is interesting to note that this way of distinguishing between having a religious affiliation and not having a religious affiliation is in accordance with the definition religions we have Judaism and Islam coming close to each other in terms of the percentage of the devotees with 1.02 and 1.58 respectively. Table-1. Religious Affiliations’ Distribution Sample Frequency Weighted Percentage NRA 7,851 16.23% CATHOLIC 14,721 41.52% PROTESTANT 11,565 27.19% JEWISH 661 1.02% MUSLIM 813 1.58% RESIDRELIG 6,084 12.45% SAMPLE 41,695 100% Denomination With respect to the self-reported importance of religion (the variable RELIGIMP, see Table-3) the statistic is extracted from a question in the survey in which the respondents were asked to express their opinion about the importance of religion by ranking it from 5 to 1 where 5 stands for very important and 1 for not important at all. Note that non religious individuals have responded to this question by “not applicable”. Attributing the value of zero to the respondents who have no religious affiliation (NRA) the average score of the importance of religion in the survey computed by weighted data is 2.95. There are two other questions dealing with religiosity and religious activity of the respondent. In one question the respondents are asked to choose among different options the one that corresponds to their frequency of religious practice with a group of people of the same faith (variable PRAGRP). The other question contains the same options however about the frequency of individual religious practice (variable PRAIND). For both questions the options are: at least once a week, once a month, at least three times a year, once or twice a year and not at all taking the values of 5 to 1. I noted that more than 50 percent of the individuals take time for religious practice at least once a month. And overall the frequency of collective religious practice is noticeably lower than individual religious practice (see Table-2). proposed by Iannaccone (1998). He defines religion as “any shared set of beliefs, activities, and institutions premised upon faith in supernatural forces”. His definition, he points out, excludes purely individualistic spirituality and systems of metaphysical thoughts including some variants of Buddhism. For sake of having a comprehensive measure of religiosity I defined the Consolidated Religiosity Index (CRI) by summing the ranking numbers of the answers to the three questions introduced in the previous paragraphs. Note that in the first questions the respondents had to rank the importance of religion from1 to 5 while in the two others the respondents’ answers were on the frequency of their individual and collective religious practice bound by 5 predetermined categories. The problematic issue in the construction of CRI was that the passage from one category to the next in the question of the frequency of religious practice would not signify the same distance in a quantitative way. More precisely in the first category the reported frequency of religious practice is 52 times a year while in the second it falls at 12 times and at 3 times in the third. On the other hand any non-linear translation of categories into a quantitative measure has the inconvenience of arbitrariness as such I opted for the simple summing method in order to arrive at the religiosity index2. CRI = RLIGIMP (between 0 and 5) + PRAGRP (between 0 and 5) + PRAIND (between 0 and 5) Table-2. Mean Religiosity Indicators by Denomination Denomination RELIGIMP PRAGRP PRAIND CRI Catholic 3.48 2.99 3.63 10.09 Protestant 3.49 3.01 3.54 10.04 Jewish 4.04 3.14 3.22 10.40 Muslim 4.22 2.96 3.97 11.17 R-Subsample3 3.54 3.02 3.62 10.18 Sample 2.95 2.52 3.02 8.48 Table-2 contains describe statistics on the average religiosity indicators (RELIGIMP, PRAGRP, PRAIND and CRI) of main religions in present in Canada along general 2 Note that William Sander, 2002, opted for the following quantification of a comparable question is the General Social Survey (GSS): “The attendance variable is recoded from the GSS as follows: never equals 0, less than once a year equals 0.5, about once or twice a year equals 1, several times a year equals 3, about once a month equals 12, two to three times per month equals 30, nearly every week equals 40, every week or more often equals 52.” But he was using Attendance per se as the dependent variable which differs from my methodology in using a composite measure. 3 R-Subsample is the subsample of individual self-reporting having a religious affiliation. In other words respondent with NRA are not included in this subsample. average. Before turning to the discussion of the methodology I also present the variables’ definition in the Table-3. Table-3. Definition of Variables Variable Definition CRI The Consolidated Religiosity Index as defined in the text. RELIGIMP The EDS question is framed as: “Using a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is not important at all and 5 is very important, how important your religion to you is?” The coverage of this question is Respondents who reported having a religion. "Not applicable" includes respondents who did not report having a religion. PRAGRP PRAIND NONMETRO TRUST SELFEMP LNINC The EDS question is framed as: “In the past 12 months, how often did you participate in religious activities or attend religious services or meetings with other people, other than for events such as weddings and funerals?” Not applicable" includes respondents who did not report having a religion. The EDS question is framed as: “In the past 12 months, how often did you do religious activities on your own? This may include prayer, meditation and other forms of worship taking place at home or in any other location.” Not applicable" includes respondents who did not report having a religion. Takes the value of 1 if the area of residence of the respondent is not a Census Metropolitan Area which is an area consisting of one or more adjacent municipalities situated around a major urban core. To form a census metropolitan area, the urban core must have a population of at least 100,000. The EDS question is framed as: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you cannot be too careful in dealing with people?” The answers were binary. Self-employed. The EDS defines self-employed as: A person who is 'self employed' earns an income directly from their own business, trade or profession, rather than being paid a specified salary or wage by an employer (EDS page. 288) Natural Logarithm of the respondents annual earning. HOURS Natural logarithm of hours worked per week. EDUC Education: Measured by years of schooling. MEDUC Mother’s education: Measured by years of schooling. FEDUC Father’s education: Measured by years of schooling. UNIVDEG Dichotomous variable taking the value of one of the respondents has obtained a university (or college) degree. EXPER Potential experience (in absence of any better measure) computed by ageyears of education-6. The resulting number is truncated so that the potential experience is smaller or equal 40. EXPERSQ Squared term of EXPER. IMMIGRANT The information is extracted from the question Genstat3 which allowed me to identify individuals born outside Canada (first generation of immigrant) and individuals born inside Canada from parents born outside Canada (second generation of immigrants. NRA CATHOLIC PROTESTANT RESIDRELIG No Religious Affiliation: It includes No religion, Agnostic, Atheist, Humanist, Personal Faith, Free Thinker, Spiritual and Other "not included elsewhere" (EDS Guide, p. 87.) It includes the following denomination: Roman Catholic, Ukrainian Catholic, Polish National Catholic Church, Other Catholic. Anglican, Baptist, Jehovah's Witnesses, Lutheran, Mennonite, Pentecostal, Presbyterian, United Church, Other Protestant. Other religions including Buddhism, Hinduism, Sikh, Other Eastern religions, Other Christian denominations such as Orthodox. The equation that constitutes the basis of the estimation is human capital earning function proposed by Mincer (1974) relating natural logarithm of earned income to natural logarithm of hours worked, years of education, years of experience both in level and in squared from, usually a dichotomous variable for having a university or college degree known as credential effect as well as dichotomous variables for gender, marital status and location. Besides these controls I have also systematically included a few extra control variables such as a dichotomous variable for self-employed status, the trusting behaviour indicator (TRUST), parents’ education and nativity status. These variables are intended to stand for unobservable individual and social characteristics that can interact with both human capital variables and religiosity as it will be explained in the upcoming section. The impact of overall religiosity is accounted for using CRI in a human capital earning function which implies that the eventual impact of religiosity on earning is monotonous. Note that Chiswick and Huang (2006) found that the impact of synagogue attendance is not monotonous in an equation for Jewish males’ earning in the US. However since CRI is itself an index more complex specification would not lead to fruitful interpretations. The problem that usually arises within the estimation of human capital earning function using such surveys is one of the missing data on income and earnings give that habitually a considerable fraction of respondents refuse to answer the questions regarding their income. And this issue raise the question of possibility of sample selectivity bias. The standard way to deal with this problem is to use one of the estimation methods developed by Heckman instead of mere OLS. In my data around 18% of the respondents of the EDS have refused to declare their income to the interviewers hence I had more than 7,000 missing data for the variable on earning (LNINC). I used both OLS and Heckman 2Stage estimation methods and both sets of results are reported. Another problem less commonly considered by researchers is the problem of omitted variable that is correlated with earning, human capital and religiosity indicators. Sander (2001) shows that education in endogenous in the equations estimating the determinants and the extent of religious activity. In order to lessen this eventual bias I added complementary control variables of parents’ education (MEDUC and FEDUC) as well as a dichotomous variable on the behavioural issue of trust and self-employed status. But I recognise that this remedy does not eliminate the problem. Finally given the limited number of categories of earning the OLS estimations are with adjusted standard errors for intra-group correlations (see: Moulton 1990). III. Religiosity and Earning Religious affiliation and to some extent overall religiosity are highly persistent through consecutive generations (according to Tomes 80% of US males followed the affiliation they have been raised with). In my data within respondents with a religious affiliation more than 87% adhere to same faith as at least one of their parents and even within respondents with NRA more than 56% follow at least one of their parents in having no religious affiliation4. Therefore one can think of religious affiliation and religiosity as a part of family background and by this virtue a constituent of a child’s endowment from family. And the familial endowment is considered as means of intergenerational transmission of economic status (for a formal model see Becker and Tomes 1979). From this stance religious denomination and religiosity are the observable and somewhat measurable aspects of this endowment that affect the child’s later economic and educational attainment. Empirically this hypothesis implies the persistent of income inequality that is serially correlated with religious denomination. While such study can be conceived and it is of great interest my cross-sectional data is not suitable for this purpose. It is also suggested that religiosity and earning can be related through the enhancing impact of religion on some economically advantageous personality traits such as discipline, diligence, trust and thrift. However recognising the possibility of the presence 4 EDS contains questions about how one’s religious faith compares to that of each of the parents. These statistics are extracted from these questions. See: EDS Guide: p. 169-172. of unobservable common cause(s) mainly of sociological and psychological order any relationship found may also be spurious (for a survey see Iannoccone 1998). In the lines below I go over some of these traits in more detail. It has been suggested that religion enhance the trait of trust and cooperative behaviour, which are economically advantageous traits (see for instance: Arrow 1972; Zak and Knack 2001). There are a number of studies that report higher degrees other-regarding behaviour in religious people. Anderson et al. (2008) through an experimental study found some weak evidence that among subjects attending religious services, increased participation is associated with cooperative behaviour in both public goods and trust games controlling for income and other demographic attributes. Note that although cooperation and trust are different issues cooperative behaviour presupposes trust. Hence the evidences for more cooperative behaviour are an indirect evidence for trusting behaviour as well. A direct test of the relationship between religiosity and trust is provided by the experimental study of Tan and Vogel (2006). They found that more religious trustees are trusted more, and such behaviour is more pronounced in more religious trusters and religious trustees are found to be trustworthier. A comparable study is the one by Johansson-Stenman et al. (2008) examining the relationship between trust and religion in Bangledesh both through survey questions and data from field experiment focusing on the cross-religion difference between Muslims and Hindus. They found that the devotees of the minority religion, Hindus, are less trusting. I looked at this question with my data using the variable TRUST and I found that trusting individuals are less religious as score slightly lower in terms of religiosity measured by CRI than not-trusting individuals. The other possible channel is the enhancing impact of religion on tendency towards entrepreneurship. This hypothesis recalls the classical thesis of Max Weber. Recently Audretsch and colleagues (2007) looked at this question through data from India. Their results suggest that certain denominations’ tenets and teaching impact negatively the tendency towards entrepreneurship. I examined this question by comparing selfemployed and paid workers in terms of religiosity and I found that in fact self-employed individuals on average score slightly lower in religiosity (measured by CRI). In the present study I do not formulate any precise hypothesis about the nature of the mechanism through which religiosity and earning may relate. I however control for these suggested channels whenever it is possible. Before doing so I present a number of bivariant relationship extracted from the data that shed light on the relevance of some of these hypothesis. The descriptive statistics on trust and entrepreneurship along the religiosity score of the residents of metropolitan areas compared to the rest of sample is presented in the Table-4. Table-4. Bi-variant Relation with Religiosity Indicators Mean Score Trusting Not Trusting SELF Paid METRO NONMETRO RELIGIMP 2.85 3.05 2.65 2.80 2.93 3.00 PRAGRP 2.51 2.53 2.33 2.36 2.49 2.58 PRAIND 2.95 3.08 2.75 2.86 3.00 3.06 CRI 8.30 8.64 7.71 8.00 8.40 8.63 46.88% 53.12% 16.28% 83.72 % 65.88% 34.12% SAMPLE Education is another, probably more controversial issue that should be considered. The popular belief prescribes that religiosity and the level of education are inversely related. The basis of such belief is the “secularization hypothesis” promoted during the past century. However data may not sufficiently support this popular belief and stark (1999) has suggested that this hypothesis is a myth. Many studies, using US data, find that education actually has a positive effect on religiosity (e.g. Ehrenberg, 1977; Hoge et al., 1996; Iannaccone 1998). The Canadian pattern seems however to be different. In the table below I report the mean of the years of schooling (EDUC) for each level of self-reported importance of religion along the weighted sample frequency of having a university or college degree. As we see in the Table-5 the relationship between religiosity and education is at first positive then it becomes negative. Table-5. Religious Indicator and Educational Attainment RELIGIMP Mean EDUC % of UNIVDEG Not important at all: 1 2 3 4 Very important: 5 12.86 12.90 12.62 12.46 11.79 23.53% 21.93% 18.46% 19.27% 16.62% NRA 12.85 22.45% Sample 12.35 19.18% Finally family structure has been suggested as another channel through which religiosity may influence economic attainment. For instance religious sanctions on divorce may increase the expected duration of marriage and hence encourage greater specialization and division of labour between spouses raising the labour market skills and earnings of one spouse (Tomes, 1984). Higher earnings of Jews were explained through their low fertility levels influencing parental investments in the children. In contrast it has been suggested that Roman Catholics face additional psychic costs of birth control, and this lowers the price of numbers of children, the resulting larger family size would tend to reduce investments in each child. I also found that there are statistically significant differences among the mean household size and number of children of religious groups under consideration. The comparative descriptive statistics are reported in the Table-10 in the annex. Mainly I found that Muslims’ average household size is larger than average Canadian while it seems that Roman Catholics have converged to the mean number of children of Protestants and Jews. In order to account for the above mentioned channels I have augmented the human capital earning function by supplementary control variables related to trust, selfemployment and marital status. 3.2. Regression Analysis In order to examine the impact of religiosity on earning I started with comparing the presence of religious belief with its absence therefore I included the dichotomous variable of NRA in the human capital earning function (augmented by additional regressors as explained in above, see also the note on Table-6). The equation is estimated by both OLS and Heckman 2Stage. The coefficient on NRA turned out to be statistically significant and positive of the magnitude of 0.039 with OLS (and 0.010 with Heckman 2Stage however the latter estimate was not statistically significant at the usual levels). These two regressions provide some evidence for slightly higher earning of respondents with NRA in average all others equal. Turning to the question of treating religiosity as a continuous variable I have augmented the human capital earning function with CRI (recall that CRI takes the value of 0 for respondents with NRA) estimating the equation again by OLS and Heckman 2Stage. The results showed that each point increase in the CRI score reduces annual earnings, all others equal, by 0.6% from the OLS estimation (and 0.4% from the Heckman estimation) which means $260 annually. Hence the results provide some evidences for a negative correlation between religiosity and earned income. The complete regressions are reported in the Table-12 in the annex. Finally I turned into examining the impact of degree of religiosity only on the individuals with a religious affiliation excluding respondents with NRA from the sample. As it is also interesting to compare the impact of religiosity across religions I have also estimated an equation in which CRI is replaced by interaction terms between CRI and religious denominations. The results of these regressions are partially reported in the Table-6 and completely in the annex (Table-13). These results suggest that higher degrees of religiosity contribute negatively to earned income by 0.6% (the coefficient reported in the first column from the right). Table-6. Human Capital Earning Function Augmented by Religiosity Catholic Protestant Jewish Muslim Others Pooled CRI (OLS) -0.008** (0.003) -0.004** (0.001) -0.003 (0.005) -0.026* (0.010) -0.013** (0.004) -0.008** (0.003) CRI (Heckman 2Stage) -0.006** (0.001) -0.005** (0.001) -0.003 (0.002) -0.024** (0.002) -0.012** (0.001) -0.008** (0.001) Note: The sample is restricted to respondents having a religious affiliation. The regression contained: EDUC, EXPER, EXPERSQ, MEDUC, FEDUC, HOURS, and dummies for gender, immigrant, locations, married, and university degree. Note that * indicates 10% level of significance while ** stand for 0.05% or lower levels of significance. N=14911. For complete report of the estimations see Table-13 in the annex. With respect to religion-specific impact of degree of religiosity no important and statistically significant difference is found between Protestants and Catholics. However for Jews the coefficient on CRI is not significantly different from zero suggesting that the degree of religiosity does not impact Jews’ earning. On the other hand the coefficient is noticeably higher for Muslim: all others equal each point of CRI reduces the average annual earnings by 2.6% (2.4% with Heckman 2Stage) which means $1130 per year. IV. Religions and Earning The question of interest in this section is an empirical one: is there any difference in terms of earning and human capital returns among different religious groups in Canada? As I have motioned in the introduction such difference has been found in the past studies to the direction of lower earnings of Catholics and higher earning of Jews. The studies of reference are the ones by Tomes and Meng and Sentence. My study differs from the previous ones in that given the important movements of person in Canada during the past two decades I have also included Muslims along Protestants, Catholics and Jews as main comparable religions (note that the fraction of Muslims in the population became more important that Jews; see Table-1). Moreover I did not exclude females from the sample given that unlike 25 years ago their participation in the labour force nowadays in important enough. Perhaps it is interesting to start with a review of the bi-variant relationship between religious denomination and annual income. As we see in the Table-7 the statistics suggest sizable discrepancies among a subset of religious groups. Mainly one observes that working Jews earn 23% more than average working Canadian and working Jewish males earn 26% more than average working Canadian males while working Muslims earn 13% less than average Canadian and working Muslim males earn 15% less than average working Canadian males. Obviously the discrepancies may be explained away through ceteris paribus analysis. But before getting to it I like to take a close look as educational attainments of the groups under consideration. From the Table-7 it can be noted that Jews enjoys a higher level of education evident from both average years of schooling and the percentage of their population that holds a university (college) degree. Working Jews have on average close to 2 more years of schooling and 51% of them hold a university degree against 23% of general working Canadians’ subsample. The perplexing issue is that Muslims also have on average 1.3 more years of schooling and the university graduate percentage of them primes the average by close to 20%. With regard to the reasons behind Jews higher educational attainment Reuven Brenner and Nicholas Kiefer (1981) proposed that because of their past cultural history of the expropriation of material wealth, Jews make greater investments in human capital, which is embodied and transportable. And with respect to Muslim I believe that the mains reason behind Muslims’ higher educational attainment is that a high fraction of Muslims are immigrants (71%) and taken together with Canadian immigration policy and its requirement on academic qualification of the immigration candidates their education is higher than average. It is noteworthy that unlike in previous studies dating back to 1980s Catholics now have the same educational attainment as Protestants (see Tomes 1984). To end this discussion I also looked at the age composition of the respondents in the working subsamples. As a matter of fact the average age of working Muslims (38 years old) is lower than average working Canadian (41 years old) while average working Jews (45 years old) are noticeably older. Noting that the measure of experience in this study is potential experience (see Table-3) it may be one of the reasons behind the observed discrepancy in mean earning within groups especially Muslims versus Jews. Table-7. Religious Affiliation, Earning and Educational Attainment General MALE FEMALE GR5 EDUC UNIVDEG NRA 44,108 47,768 37,502 1.27 13.58 26.19% CATHOLIC 41,001 45,731 35,276 1.30 13.17 22.32% PROTESTANT 44,059 49,903 37,058 1.35 13.21 21.27% JEWISH 52,124 59,451 43,339 1.37 15.35 51.43% MUSLIM 37,008 40,326 30,479 1.32 14.49 42.91% OTHERS 40,774 45,558 33,738 1.35 12.37 24.32% W-Subsample 42,390 47,209 35,983 1.31 13.19 23.60% SAMPLE 32,984 39,475 26,439 1.49 12.35 19.18% Note: Date weights are applied. Reported income is in Canadian dollars. Note that this subsample included working respondents only. This fact, the age composition, added to the fact that the proportion of immigrants compared to native born are much higher within Muslims subgroups suggest that the noted mean earning differential between Muslims and the rest of the sample may be explained away by potential experience and nativity status but not for the Jewish differential. With this introduction I move to ceteris paribus analysis of the data. 5 GR stands for Gender Ratio, the ratio of male to female earning. This differentiation is made primarily for informational reasons. It is also noteworthy that although previous studies (Tomes 1984, 1985) excluded females from the sample Tomes suggested that the female side of labour market may make a substantial difference especially with respect to Jewish earrings i.e. Jewish females, he suggested, earned less than average Canadian female to the point that it could more than compensate the Jewish males’ premium. We see that his insight preserved some relevance even after 25 years since Jews have the highest GR ratio (the highest male-female earning inequality ratio) within all religious groups. 4.2. Regression Analysis In the lines below I report two sets of regressions where in the first the religious affiliation differential is assumed to be additive and in the second it is accounted for by allowing differentiated returns to human capital variables. Regarding the first specification, additive impact of religious groups, I report three separate regressions: in the first regression the whole sample of working respondents is considered while the two others concern the subsamples of self-employed respondents and paid-workers respectively in separate regressions. The reason was to gain information about the persistence of the earning differential in these two separate parts of labour market. I opted to present the result from Heckman 2Stage estimation in the test while reporting the OLS results in the annex (see Table-15). Note that they did not differ from each other by a great degree. Table 8. Heckman 2Stage Estimation of HCEF with Additive Impact of Religions Denomination POOLED SELEMPLOYED PAID WORKER NRA 0.067** (0.010) 0.024 (0.075) 0.077** (0.010) CATHOLIC 0.067** (0.009) 0.022 (0.031) 0.073** (0.009) PROTESTANT 0.085** (0.009) 0.053 (0.078) 0.088** (0.010) JEWISH 0.105** (0.024) 0.120 (0.146) 0.093** (0.027) MUSLIM -0.146** (0.022) -0.309* (0.179) -0.113** (0.023) 26706 (Censored: 7756) 3686 (Censured: 799) 23020 (Censured: 6957) -0.105** (0.030) -1.554 (1.750) -0.073** (0.028) OBS. LAMBDA Note : The reference group is other religions (RESIDRELIG). The regression contained: EDUC, EXPER, EXPERSQ, MEDUC, FEDUC, HOURS, and dummies for gender, immigrant, locations, married status, university degree, (and self-employed only in the pooled regression). Note that * indicates 10% level of significance while ** stand for 0.05% or lower levels of significance. It become clear that when the impact of religion is assumed to be additive all else equal Jews earn more than 10% higher that reference group. While the earnings of NRA and Catholics seem to be similar by being around 6% higher than the reference group Protestants fare slightly better them (the difference is statistically significant) and slightly worse than Jews. Muslims earn close 15% less than the references group which is by far the largest statistically significant differential. When I repeated the regression with two separate subsamples one for self-employed and the other for paid worker I found that the earning differential drastically increases in the subsample of self employed for Muslims and Jews and to some extent Protestants. The noteworthy result is the coefficient on Muslims that shows 30% earnings less than the references group. In the paid workers subsample however the earning differential of Muslims declines to -11% while the coefficients on other religious groups are not significantly different from each other. In the second set of regressions I allowed the coefficients of human capital variables to vary with religious affiliations. Table-9. Heckman 2Stage Estimation of HCEF by Religions NRA Catholic Protestant Jewish Muslim Others Pooled EDUC 0.034** (0.003) 0.029** (0.002) 0.030** (0.002) 0.024** (0.006) 0.024** (0.004) 0.026** (0.001) 0.030** (.002) EXPER 0.028** (0.002) 0.022** (0.002) 0.020** (0.002) 0.036** (0.007) 0.001 (0.006) 0.020** (0.003) 0.023** (0.001) EXPERSQ -.0004** (.0000) -.0003* (.0000) -.0002 (.0000) -.0007 (.0002) .0002 (.0002) -.0003** (.0001) -.0003** (.0000) UNIVDEGRE 0.099** (0.019) 0.164** (0.013) 0.157** (0.016) 0.154** (0.060) 0.166** (0.052) 0.122** (0.021) 0.137** (0.009) Note : The reference group is other religions (RESIDRELIG). The regression contained: EDUC, EXPER, EXPERSQ, MEDUC, FEDUC, HOURS, and dummies for gender, immigrant, locations, married status, university degree, and self-employed status. Note that * indicates 10% level of significance while ** stand for 0.05% or lower levels of significance. OBS=18950 (Censored: 7756) The results show that there is no substantial difference on the return to education among the religious groups under consideration. It contrasts Becker’s conjecture that the high incomes and achievements of Jews are explained by high marginal returns to education (1981). My results suggest that there is however a sizable difference on the return to experience between Jews and others. The experience-earning profile of Jews is steeper than respondents with NRA, Catholics and Protestant while the experience factor turns out to have no economically and statistically significant impact on the Muslims earning. On the other hand the credential effect (the coefficient of the variable UNIVDEG) is significantly higher for Muslims (around 5% higher contribution to earnings compared to the average of Catholic, Protestants and respondents with NRA). The credential effects turns out to be quite smaller for Jews compared to other groups, moreover it is not statistically significant. The absence of credential effect for Jews has been also found by Tomes (1984). Note that the results from an OLS estimation of the same equation are reported in the Table-16 in the annex. Conclusion Tomes said “The returns to research by economists on religion and earnings have been small. One problem is that the lack of robust stylized facts leads to the rejection of most simple hypotheses.” and the statement remains true after 25 years. Now that one should mainly decide religion is still and may eventually remain an important aspect of human culture it is legitimate to study its economic impact as systematically as other sociocultural factors such race, ethnicity and gender. This paper was conceived to contribute to the creation of stylised facts regarding the relationship between religions, religiosity and labour market’s main indicators. Using Canadian Ethnic Diversity Survey I examined the relationship between religions, religiosity and earning. With respect to the impact of overall religiosity on earning the relationship uncovered, although quantitatively slight, was negative. This result is in contrast with common belief hold about the situation is the US according to which the relationship between religiosity and earning is positive. Examining the crossdenomination difference in earning and human capital return the results show that there are indeed statistically significant discrepancies among religions. These differences are more accentuated within the self-employed segment of Canadian labour market compared to paid workers’ segment. In this paper I have also explicitly accounted for Muslims and the results shows that their earning is significantly lower than average while Jews’ earnings are significantly higher. More precisely I found the experience-earning profile of Jew is steeper than others while experience is not a relevant factor in explaining Muslims’ earnings. An additional note might be in order with respect to Muslims’ earning and from there their economic condition in Canada. As it is reported in the Table11 in the annex the average family size and number of children are larger than average Canadian (with respect to household size Muslims’ average is 3.872 persons against 2.933 persons in Canada). Taken together, the lower earnings and the larger family size of Muslims make this affiliation a good predictor of economic disadvantage in Canada. This paper was a first step in updating the knowledge of the relationship between earning and religion in Canada. This paper also showed how Canadian pattern differ from the US pattern in terms of the relationship between earning, educational attainment and religiosity. However the paper was largely focused on uncovering descriptive relationships. Certainly future studies on the same question using other data can help showing the robustness of the results. Moreover various studies can be conceived aimed at explaining the eventual reasons behind the relationships that I found in the present paper. References Anderson Lisa R., Jennifer M. Mellor and Jefferey Milyo (2008), Did the Devil Make Them Do It? The Effects of Religion in Public Goods and Trust Games, College of William and Mary, Department of Economics, Working Paper #20. Arrow, K. J. (1972), Gifts and Exchanges, Philosophy and Public Affairs, Volume 1, p. 343-462. Audretsch, David B. Werner Boente and Jagannadha Pawan Tamvada (2007), Religion and Entrepreneurship, Max-Planck Institute of Economics at Jena Working Paper. Azzi, Corry and Ronald G. Ehrenberg (1975), Household Allocation of Time and Church Attendance, J. Polit. Econ., 83:1, p. 27–56. Barro, Robert J. And Rachel M. McCleary (2006), Religion and Economy, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20:2, 49-72. Becker, Garry S. (1981), A Treatise on the Family, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Becker, Garry S. and N. Tomes (1979), An equilibrium theory of the distribution of income and intergenerational mobility, Journal of Political Economy, 87: 1153-89 Blunch, Niels-Hugo (2007), Religion and Human Capital in Ghana, CWPE 0770. Boppart Timo, Josef Falkinger, Volker Grossmann, Ulrich Woitek and Gabriela Wüthrich (2008), Qualifying Religion: The Role of Plural Identities for Educational Production, Institute for Empirical Research in Economics University of Zurich, Working Paper Series, ISSN 1424-0459 Chiswick, Barry R. (1983), The Earnings and Human Capital of American Jews, J. Human Res., 18:3, p. 313–36. Chiswick, Barry R. (1985), The Labor Market Status of American Jews: Patterns and Determinants, American Jewish Yearbook, 85, p. 131–53. Chiswick Barry R. and Jidong Huang (2006), The Earnings of American Jewish Men: Human Capital, Denomination and Religiosity, IZA DP 2301. Durlauf Steven N., Andros Kourtellos and Chih Ming Tan (2006), Is God in the Details? A Re-examination of the Role of Religion in Economics Growth, Working Paper. Ehrenberg, Ronald G. (1977), Household Allocation of Time and Religiosity: Replication and Extension, J. Polit. Econ., 85:2, p. 415–23. Glaeser E. L. And B. Sacerdote (2001), Education and Religion, Harvard Institute of Economic Research, Discussion Paper Number 1913. Guiso, Luigi, Paolo Sapienza and Luigi Zingales (2003), People’s Opium? Religion and Economic Attitudes, Journal of Monetary Economics, 50: 225–282. Iannaccone, Laurence R. (1998), Introduction to the Economics of Religion, Journal of Economic Literature, 36, p. 1465–1496. Lehrer, Evelyn L. (2008), The Role of Religion in Economic and Demographic Behaviour in the United States: A Review of the Recent Literature, IZA DP No. 3541. Meng, R., and J. Sentance, (1984) Religion and the determination of earnings: further results, Canadian Journal of Economics, 17:3, p. 481-8. Mincer, J. (1974) Schooling, Experience and Earnings, New York: NBER. Moulton, B.R. (1990), An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units, Review of Economics and Statistics, 72:334–338. Nolan, Marcus (), Religion, Culture and Economic Performance, Working Paper. Pyle, Ralph E. (1993) Faith and Commitment to the Poor: Theological Orientation and Support for Government Assistance Measures, Soc. Rel., 54:4, p. 385–401. Sander, William (2002), Religion and Human Capital, Economics Letters, 75: 303–307. Stark, Rodney, Laurence R. Iannaccone, and Roger Finke. (1996) Religion, Science, and Rationality, Amer. Econ. Rev., 86:2, p. 433–37. Steen Todd P. (1996), Religion and earnings: evidence from the NLS Youth Cohort, International Journal of Social Economics, 23:1, p. 47-68. Sullivan, Dennis H. (1985), Simultaneous Determination of Church Contributions and Church Attendance, Econ. Inquiry, 23:2, p. 309–20. Tan Jonathan H. W. And Claudia Vogel (2008), Religion and Trust: An experimental Study, Journal of Economic Psychology, 29: 832–848 Tomes, N. (1983), Religion and the rate of return on human capital: evidence from Canada, Canadian Journal of Economics, 16:1, p. 122-38. Tomes, N. (1984), The effects of religion and denomination on earnings and the returns to human capital, Journal of Human Resources, 19:4, p. 472-88. Tomes, N. (1985), Religion and the earnings function, American Economic Review, 75:2, p. 245-50. Weber, M. (1958) The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Talcott Parsons, New York: Free Press. Zak P. J. And S. Knack (2001), Trsut and Growth, Economic Journal, 111:295-321. Annex: Additional Tables Table-10. Descriptive Statistics on Variables6 Variable Observation Mean Std. Dev Min Max CRI 40551 8.975 4.536 3 15 RELIGIMP 40870 3.100 1.591 1 5 PRAGRP 40940 2.719 1.624 1 5 PRAIND 40747 3.167 3.167 1 5 MONTREAL 41695 0.100 --- --- --- TORONTO 41695 0.204 --- --- --- VANCOUVER 41695 0.088 --- --- --- METRO 41695 0.315 --- --- --- NONMETRO 41695 0.294 LNINC 19157 10.585 0.456 9.903 11.290 HOURS 22190 3.664 0.272 2.302 3.912 EDUC 41695 12.637 3.937 7 20 MEDUC 41695 10.092 3.530 7 16 FEDUC 41695 10.197 3.710 7 16 AGE 41695 41.275 15.546 16 65 FAMALE 41695 0.529 --- --- --- MARRIED 41695 0.575 --- --- --- IMMIGRANT 41695 0.256 --- --- --- EXPER 22185 21.259 14.004 0 40 NRA 41695 0.188 --- --- --- CATHOLIC 41695 0.353 --- --- --- PROTESTANT 41695 0.277 --- --- --- JEWISH 41695 0.016 --- --- --- 6 The statistics are computed without weighting. MUSLIM 41695 0.0195 --- --- Table 11. Descriptive Statistics on Family Structure by Religion Number of Children (Std. Dev.) Household Size (Std. Dev.) NRA 0.601 (0.961) 2.902 (1.349) CATHOLIC 0.715 (1.012) 2.893 (1.330) PROTESTANT 0.713 (1.034) 2.791 (1.326) JEWISH 0.659 (1.045) 2.853 (1.434) MUSLIM 1.238 (1.335) 3.872 (1.422) OTHERS 0.772 (1.056) 3.303 (1.459) SAMPLE 0.711 (1.025) 2.933 (1.365) Denomination --- Table-12. Dependant Variable: Natural Logarithm of Annual Income Indep. Variables OLS OLS Heckman 2Stage Heckman 2Stage 0.010 (0.007) ---- NRA 0.039** (0.007) CRI ---- -0.006** (0.002) ---- HOURS 0.386** (0.088) 0.383** (0.087) 0.390** (0.011) 0.388** (0.010) EDUC 0.032** (0.008) 0.033** (0.009) 0.030** (0.002) 0.031** (0.002) MEDUC 0.006** (0.001) 0.006** (0.001) 0.004** (0.001) 0.004** (0.001) FEDUC 0.001 (0.001) 0.001 (0.001) 0.001 (0.001) 0.002 (0.001) EXPER 0.026** (0.009) 0.026** (0.009) 0.023** (0.001) 0.024** (0.001) EXPERSQ -0.0004** (0.0001) -0.0004** (0.0001) -0.0003** (0.0000) -0.0003** (0.0000) FEMALE -0.212** (0.078) -0.205** (0.075) -0.207** (0.007) -0.205** (0.007) MARRIED 0.085** (0.027) 0.089** (0.027) 0.083** (0.006) 0.087** (0.006) -0.038** (0.020) -0.033** (0.019) -0.024** (0.006) -0.021** (0.006) IMMIGRANT ----- -0.004** (0.001) TRUST 0.047** (0.017) 0.045* (0.017) 0.041** (0.007) 0.040** (0.007) SELFEMP -0.030 (0.080) -0.031 (0.081) -0.031 (0.008) -0.031 (0.008) UNIVERSITY 0.138** (0.038) 0.138** (0.038) 0.137** (0.009) 0.135** (0.009) TORONTO 0.072 (0.035) 0.074* (0.036) 0.056** (0.008) 0.058** (0.008) MONTREAL -0.032 (0.023) -0.039* (0.022) -0.032** (0.010) -0.036** (0.010) VANCOUVER 0.001 (0.020) -0.004 (0.019) -0.012 (0.010) -0.015 (0.011) NONMETRO -0.046** (0.011) -0.047** (0.011) -0.053** (0.007) -0.053** (0.007) CONSTANT 8.307** (0.471) 8.369** (0.451) 8.420** (0.057) 8.440** (0.058) OBS. 18950 18950 26706 (Censured: 7756) 26706 (Censured: 7756) R2 0.3358 0.3392 ---- ---- LAMBDA -0.102 (0 .030) -0.090 (0.030) Note The reported coefficients are rounded to three decimal points. The standards errors are reported in the parentheses below. Note that * indicates 10% level of significance while ** stand for 0.05% or lower levels of significance. The omitted variable within locations category is Other Metropolitan areas. Table-13. Dependant Variable: Natural Logarithm of Annual Income Indep. Variables OLS HECKMAN 2Stage OLS HECKMAN 2Stage HOURS 0.373** (0.084) 0.393** (0.012) 0.371** (0.082) 0.391** (0.012) EDUC 0.031** (0.008) 0.030** (0.002) 0.031** (0.008) 0.029** (0.002) MEDUC 0.006** (0.001) 0.005** (0.001) 0.005** (0.001) 0.004** (0.001) FEDUC 0.001 (0.001) 0.001 (0.001) 0.002 (0.001) 0.001 (0.001) EXPER 0.026** (0.009) 0.022** (0.002) 0.026** (0.009) 0.021** (0.002) EXPERSQ -0.0004* (0.0002) -0.0003** (0.0001) -0.0004* (0.0002) -0.0003** (0.0001) FEMALE -0.206** (0.080) -0.208** (0.007) -0.212* (0.081) -0.213** (0.007) MARRIED 0.083** (0.024) 0.083** (0.007) 0.082** (0.025) 0084** (0.007) IMMIGRANT -0.021** (0.019) -0.012* (0.007) -0.007 (0.015) -0.003** (0.007) TRUST 0.054** (0.019) 0.104** (0.013) 0.053** (0.015) 0.043** (0.007) SELFEMP -0.027 (0.081) -0.024** (0.009) -0.027 (0.080) -0.025** (0.009) UNIVERSITY 0.149** (0.041) 0.088** (0.015) 0.154** (0.041) 0.151** (0.011) TORONTO 0.069 (0.036) 0.059** (0.008) 0.077* (0.040) 0.066** (0.009) MONTREAL -0.042 (0.026) -0.035** (0.011) -0.033 (0.028) -0.033** (0.011) VANCOUVER 0.005 (0.028) -0.008 (0.013) 0.019 (0.032) 0.008 (0.013) NONMETRO -0.049** (0.010) -0.053** (0.008) -0.052** (0.011) -0.057** (0.008) CRI -0.008** (0.003) -0.008** (0.001) ----- ----- CRICATH ------- ------- -0.008** (0.003) -0.006** (0.001) CRIPRO ------ ------ -0.004** (0.001) -0.005** (0.001) CRIJEW ------ ------ -0.003 (0.005) -0.003 (0.002) CRIMUS ------- ------- -0.026** (0.010) -0.024** (0.002) CRIOTH -------- -------- -0.013** (0.004) -0.012** (0.001) CONSTANT 8.442** (0.432) 8.487** (0.064) 8.462** (0.422) 8.516** (0.064) OBS. 14911 21472 (6561) 14911 21472 (6561) R2 0.3379 ---- 0.3453 ----- ----- -0.091** (0.032) ----- -0.099** (0.032) LAMBDA Note The reported coefficients are rounded to three decimal points. CRICATH is the interaction term between CRI and Catholic. CRIPRO is the interaction term between CRI and Protestant. CRIJEW is the interaction term between CRI and Jewish. CRIMUS is the interaction term between CRI and Muslim and CRIOTH is the interaction tern between CRI and RESIDRELIG. The standards errors are reported in the parentheses below. Note that * indicates 10% level of significance while ** stand for 0.05% or lower levels of significance. The omitted variable within locations category is Other Metropolitan areas. Table 14. First Stage Regressions for Heckman 2-Satge Estimations Independent Variable: Dichotomous Variable of Declaring One’s Income Indep. Variables (1) (2) (3) (4) EDUC 0.092** (0.003) 0.092** (0.003) 0.096** (0.004) 0.096** (0.004) MEDUC 0.011** (0.003) 0.011** (0.003) 0.008** (0.004) 0.008** (0.004) FEDUC 0.000 (0.003) -0.000 (0.003) 0.002 (0.003) 0.002 (0.003) AGE 0.170** (0.045) 0.170** (0.005) 0.175** (0.005) 0.175** (0.005) AGESQ -0.002** (0.000) -0.002** (0.000) -0.002** (0.000) -0.002** (0.000) FEMALE -0.308** (0.018) -0.306** (0.018) -0.314** (0.020) -0.314** (0.020) MARRIED 0.010 (0.021) 0.010 (0.021) 0.019 (0.023) 0.019 (0.023) IMMIGRANT -0.066* (0.018) -0.070** (0.019) -0.067** (0.021) -0.067** (0.021) SELFEMP 0.077** (0.027) 0.074** (0.027) 0.104** (0.030) 0.104** (0.030) UNIVERSITY -0.310** (0.029) -0.310** (0.029) -0.338** (0.033) -0.338** (0.033) TRUST 0.299** (0.018) 0.230** (0.018) 0.303** (0.021) 0.303** (0.021) -3.418** (0.103) -3.421** (0.103) -3.585** (0.116) -3.585** (0.116) OBS. 26706 26706 21472 21472 PSEUDO-R2 0.1997 0.2001 0.2122 0.2122 CONSTANT Note The first regression corresponds to the estimation of HCE function augmented by NRA and the second to the one augmented by CRI. The third is augmented by CRI with the R-Subsample. The forth column is when the equation is augmented by interaction terms of CRI and religion. Table -15. OLS Estimation of HCEF with Additive Impact of Religions Denomination POOLED SELEMPLOYED PAID WORKER NRA 0.097** (0.028) 0.024 (0.028) 0.105** (0.035) CATHOLIC 0.058** (0.019) 0.022 (0.031) 0.065** (0.021) PROTESTANT 0.092** (0.032) 0.076 (0.026) 0.096* (0.038) JEWISH 0.123* (0.060) 0.167 (0.086) 0.099 (0.050) MUSLIM -0.175* (0.079) -0.362* (0.147) -0.132 (0.068) OBS. 18950 2887 16063 R2 0.3433 0.2325 0.3771 Note : The reference group is other religions (RESIDRELIG). The regression contained: EDUC, EXPER, EXPERSQ, MEDUC, FEDUC, HOURS, and dummies for gender, immigrant, locations, married status, university degree, (and self-employed only in the pooled regression). Note that * indicates 10% level of significance while ** stand for 0.05% or lower levels of significance. Table-16. OLS Estimation of HCEF by Religions NRA Catholic Protestant Jewish Muslim Others Pooled EDUC 0.034** (0.009) 0.031** (0.008) 0.035** (0.009) 0.023 (0.014) 0.026** (0.004) 0.028** (0.004) .032** (0.008) EXPER 0.027** (0.007) 0.027** (0.008) 0.024** (0.009) 0.043** (0.016) 0.008 (0.011) .029** (0.014) .026** (0.009) EXPERSQ -.0004* (.0001) -.0004** (.0001) -.0003* (.0000) -.0007* (.0003) .0000 (.0003) -.0005 (.0003) -.0004** (.0001) UNIVDEGRE 0.102** (0.035) 0.171** (0.047) 0.131 (0.065) 0.193 (0.142) 0.156* (0.100) 0.141** (0.050) 0.139** (0.038) Note : The reference group is other religions (RESIDRELIG). The regression contained: EDUC, EXPER, EXPERSQ, MEDUC, FEDUC, HOURS, and dummies for gender, immigrant, locations, married status, university degree, and self-employed status. Note that * indicates 10% level of significance while ** stand for 0.05% or lower levels of significance. . N=18950, R2=0.3445