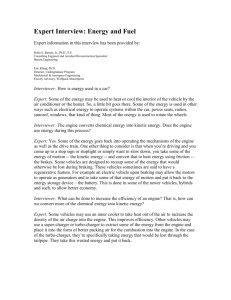

Future Light-Duty Vehicles:

advertisement