CAN PLACEMENT OF ADOLESCENT BOYS IN FOSTER CARE BE HARMFUL?

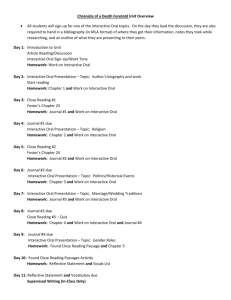

advertisement