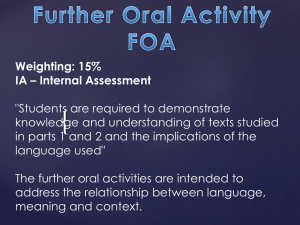

“Un-American” or Unnecessary? America’s Rejection of Compulsory

advertisement