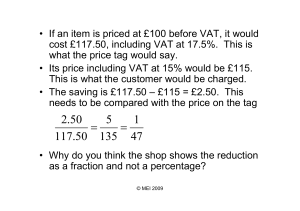

VAT Revisited

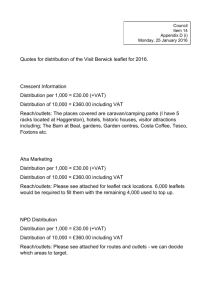

advertisement