Preliminary, please do not quote. ————————— HOW WERE CANADIAN LABOUR MARKET

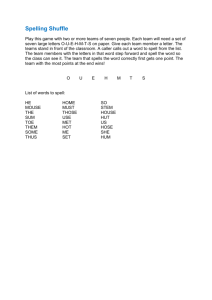

advertisement

Preliminary, please do not quote.

—————————

HOW WERE CANADIAN LABOUR MARKET

TRANSITIONS AFFECTED BY 1996 EMPLOYMENT

INSURANCE REFORM?

KAILING SHEN

Abstract. The 1996 Employment Insurance (EI) reform involved

one of the most significant changes of the Canadian EI program in

its history. It was designed to speed up the re-employment process

of job losers.

This paper is an evaluation of this reform’s impact on labour

market transitions. In particular, I examine the impact of this

reform on the distributions of both employment and unemployment

spells of non-seasonal and seasonal sectors, taking the multiple

changes in this reform as a package.

I use an underlying discrete proportional hazard model combined with a heaping effect measurement model. The spell data

comes from the confidential Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics. This study found some evidence that the 1996 EI reform might

have discouraged tailoring behaviour and on average, the probability for an employment spell to last more than 50 weeks increased

and the probability for an unemployment spell to last more than

50 weeks decreased after the reform, both in non-seasonal as well

as seasonal sectors. This study also revealed the impact of the

1996 EI reform distributed unevenly across different worker and

job types.

Date: May 18 2004.

I would like to thank David A. Green for answering my numerous questions and

providing continuous guidance in this work. I would also like to thank Craig Riddell,

Shinichi Sakata, Thomas Lemieux, Nicole Fortin, and Paul Beaudry for continuous

guidance, help, and encouragement. Assistance of Lee Grenon, James P. Croal

of the Research Data Centre at the University of British Columbia in using the

SLID data is highly appreciated. Special thank for Michel Y Bédard of the Human

Resources Development Canada(HRDC) for helping me get EI-region related data.

Any remaining errors are my own. The research and analysis are based on data from

Statistics Canada and the opinions expressed do not represent the views of Statistics

Canada. email: kailings@interchange.ubc.ca address: Department of Economics,

the University of British Columbia.

1

2

1. Introduction

First introduced in 1940, Employment Insurance (EI) program has

been the most prominent federal policy in Canada’s labour market

since then. Statistics shows there are 1.9 million new EI claims for

income benefits in year 2000/01, and 88% of paid workers were EI

benefit eligible as of December 20001.

To accommodate economic growth and fluctuation, Canada’s EI program has experienced a series of changes over the years. Studies on the

EI program’s impact have provided important evidence for these EI

program changes. Evaluation of these changes is also an important

part of EI studies. The 1996 EI reform involved one of the most significant changes of the Canadian EI program in its history. This paper

examines the impact of 1996 EI reform on both employment and unemployment spell distributions.

The 1996 EI reform is known as shifting the focus of EI program from

subsidizing unemployed workers to speeding up the re-employment

process of job losers. Four of the most noticeable changes in this

reform are: replacement of week system by hour system, reduction

of maximum benefit duration, longer entrance requirement for new

entrants/re-entrants, and introduction of worker-side experience rating.

While there have been many empirical studies on Canada’s EI program’s impacts on labour market transitions, for example, Green and

Riddell(1993, 1997), Baker and Rea (1998), Ham and Rea (1987). Most

of them focus on only one type of spell, either employment or unemployment. But, evidence on both of these two types of spells is needed

to understand the impact of the 1996 EI reform’s impact. Why? First,

the overall EI program expense depends on these two types of spells

jointly. While the distribution of employment spells determines the

entry rate of EI benefit collection spells, the distribution of these EI

collection spells are closely correlated with unemployment spells. Second, workers’ welfare and the health of the economy depend on both

types of spells. Theoretically, this EI reform could reduce unemployment spell duration but still indirectly hurt subsequent employment

stability if job-match quality deteriorates due to poorer search.

12002

EI Monitoring and Assessment Report

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

3

Therefore, the key feature of this study is that I study employment

and unemployment spells jointly. In this study, employment and unemployment spells are defined coherently, constructed from a common

data source, and analyzed using the same econometric setup. Thus,

this paper allows us to combine evidence from both types of spells to

evaluate the impact of the 1996 EI reform on the overall labour market

transitions in a straightforward way.

The second feature of my study is that the multiple simultaneous

changes in this reform are treated as a package. Most empirical EI

studies have been focused on the marginal effect of individual EI parameters. While others, such as Clark and Summers (1982), simultaneously consider multiple aspects of an EI program. I choose, instead, to

take the multiple changes in 1996 EI reform as a single package because

it is infeasible to separate individual impacts as they interact with each

other.

The third feature of this study is that spells are grouped according

to seasonality. Seasonal2 and repeated3 EI users, as defined by the

EI administration, make far more frequent EI claims than the average

workers, whose probability to make EI claims in one year period is only

12%4. Furthermore, seasonal users constitute about 80% of repeated

EI users. These seasonal repeated EI users5 alone made 30%6 of the

EI claims in 1995/96. In this sense, EI financial resources have been

allocated to seasonal industries disproportionately.

Green and Sargent (1998) pointed out that seasonal workers, unlike

non-seasonal ones, face a known, high probability of job separation and

re-employment and they tend to deal with same employers repeatedly.

These seasonal workers counts on EI benefits to be a substantial and

regular part of their annual income. The pre-reform EI program is often

seen to have indirectly subsidized seasonal firms without fulfilling an

insurance purpose, thus it prevented both physical and human capital

relocation. To address this problem, the 1996 EI reform introduced

2Seasonal

EI uses are defined as “people who had started previous claims at

about the same time of year as their current one”.

3Frequent EI users are defined as “individuals who had three or more claims

for regular or fishing benefits within the previous five years”.

4This is calculated as the ratio of new claims over the labour force size in a

typical year in 1990s.

5Seasonal repeated EI users are defined as both seasonal and frequent EI users.

These definitions are used for official EI program annual evaluation.

6This figure is derived from 1998 EI Monitoring and Assessment report.

4

KAILING SHEN

worker-side experience rating, which made repeated EI usage much

less profitable. Thus, the 1996 EI reform is expected to have different

impacts on seasonal and non-seasonal spells.

This paper’s data comes from confidential Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) data. Eight groups of sample spells are created:

employment and unemployment spells in non-seasonal and seasonal

sectors during the pre-reform and post-reform periods. An underlying discrete proportional hazard model combined with a heaping effect

measurement model is estimated in each of these eight group of sample

spells.

The major problem in identifying the EI reform’s impacts using a

pre- and post- reform comparison is due to the improving macroeconomic conditions over the study period. The difference in labour

market transitions between post-reform and pre-reform periods could

be due to gradually improving macroeconomic conditions as well as

changes made in the 1996 EI reform. In this study, I used raw unemployment rate derived from Labour Force Survey as control for macroeconomic conditions. Lemieux and MacLeod (2000) found evidence that

workers propensity of making EI claims is affected by their own experience after the change in the system in earlier 1970s. If similar things

happened in this 1996 EI reform, then the labour market might need

several years to adjust to changes of 1996 EI reform fully, although

majority of the EI reform’s changes have come into effect in January

1997. In this sense, the evidence found in my study only reflect the

1996 EI reform’s impacts on the labour market transitions in the short

run.

This study found some evidence that the 1996 EI reform might have

discouraged tailoring behaviour and on average, the probability for an

employment spell to last more than 50 weeks increased and the probability for an unemployment spell to last more than 50 weeks decreased

after the reform, both in non-seasonal as well as seasonal sectors. This

study also revealed the impact of the 1996 EI reform distributed unevenly across different worker and job types.

The rest of this paper is organized in six parts. Section 2 outlines

1996 EI reform’s four major changes and their expected impacts; section 3 discussed how I construct sample spells from SLID as well as

descriptive statistics of these sample spells; section 4 discuss the hazard

model with heaping effect that I used in estimation; section 5 presents

the estimation results; section 6 presented the simulation results using

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

5

the actual worker and job types in the data; section 7 briefly review

related studies and concludes.

2. Four major changes in the 1996 EI reform

Based on Variance Entrance Requirement (VER) system, 1996 EI

reform made four major changes that affect EI benefit duration in the

regular benefit part of EI program.

VER is a feature that distinguish Canada’s EI program from similar

programs of other countries. In this VER system, unemployed workers EI benefit durations depend on both previous employment history

as well as local EI region’s unemployment rate. Higher local unemployment rate will lead to longer EI benefit duration and shorter EI

entrance requirement.

VER leads to build-in correlation between EI generosity and local

labour market, which makes controlling for local labour market much

difficult in EI studies. It also leads to build-in lagged duration dependence between employment duration and subsequent unemployment

duration, which means any change in the EI program will potentially

affect distributions of both employment and unemployment spells as

well as their correlation.

It is based on such VER system that the 1996 EI reform introduced

the following four major changes that substantially altered the incentives of EI program.

2.1. replacement of week system by hour system. In the prereform week system, when applying for EI benefit, workers’ employment history is measured by calender week. Among the four types of

EI insurable jobs, (a)less than 15 hours per week, (b)15 to 34 hours

per week, (c)35 hours per week, and (d) more than 35 hours per week,

in the week system, group (a) jobs weren’t counted in EI benefit calculation. Moreover, for all calendar weeks with jobs whose weekly hours

above the 15 hours threshold, number of hours worked did not affect EI

benefit duration. To recognize development of workplace practice, the

new hour system counts every hour worked in every EI insurable jobs

in EI benefit calculation. The post-reform benefit duration schedule

is rewritten in terms of hours using 35 hours/week ratio based on the

pre-reform schedule.

6

KAILING SHEN

Although this revision lead to no difference in the EI benefit calculation for single-job holders with group (c) jobs, the revision did affect

other workers. The benefit of hour system is most obvious for multiple

job holders with only group (a) jobs. Single job-holders, workers whose

jobs belong to group (a) and (d), also benefit from the change. At the

same time, those who have jobs in group (b) now will need to work

longer to get same EI benefit as they could pre-reform. Besides these,

this week to hour change could also lead to higher participation rate

as individuals who are indifferent about whether to participate or not

could be attracted to the labour force if the jobs available to them are

mostly group (a) jobs.

2.2. Reduction of maximum benefit duration. The up-limit of

EI benefit duration pre-reform was 50 weeks and it is now 45 weeks.

Since EI benefit duration depends on workers preceding employment

history as well as local EI unemployment rate, only workers with more

than 40 EI employment weeks in a region with at least 10.1% unemployment rate would be eligible for more than 45 weeks of benefit

pre-reform. Therefore, from a static point of view, only these workers

are affected by this reduction of maximum benefit duration. But in a

dynamic view, the employment behaviour is endogenously determined

and longer EI benefit set in the EI schedule constitute contributes to

workers’ incentive for longer employment spells. Thus, the reduction

of maximum benefit duration could result in less number of cases that

are eligible for more than 45 weeks of EI benefit and thus to less stable

employment. In other words, the whole distribution of employment

spells could be negatively affected by this change.

2.3. Longer entrance requirement for new-entrants/re-entrants.

New-entrants/re-entrants constitute a special group of EI users. They

are defined as having less than 14 weeks pre-reform, or 490 hours postreform, of EI insurable employment and EI benefit collection, during

the 52 weeks preceding their current EI qualification period7. Under VER, new-entrants/re-entrants are treated differently as to their

entrance requirement8 . All other EI users’ entrance requirements depend on local unemployment rate but new-entrants/re-entrants face

uniform entrance requirement. Pre-reform, they would need 20 weeks

7EI

qualification period is used to calculated EI employment for benefit calculation purpose. It is defined as the 52 weeks period preceding the employment

separation, or since the beginning of last EI claim, whichever is shorter.

8The minimum EI insurable employment required to get any EI benefit.

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

7

of employment to be eligible for EI benefit. Post-reform, the entrance

requirement for new-entrants/re-entrants is 910 hours of employment,

which is equivalent to 26 weeks using 35 hours per week ratio. It is

in this sense, the entrance requirement for new-entrants/re-entrants

became longer post-reform.

The increased entrance requirement for new-entrants/re-entrants partly

offsets the positive labour market participation effect of hour system

as discussed above. It also partly offsets the potential negative impact of reduced maximum benefit weeks on employment stability as it

reenforce the incentives for strong labour market attachment.

Jointly these first three changes encourage workers to take occasional/irregular jobs or even less stable jobs while at the same time keep

strong labour market attachment. The whole distribution of employment and unemployment spells could be affected by these changes.

Moreover, these changes will bring differential changes across worker

types.

2.4. Introduction of worker-side experience rating. Worker-side

experience rating discouraged repeated EI users. It punished EI users

in two aspects, 1) replacement ratio9 by intensity rule; and, 2) EI benefit repayment conditions10 in clawback rule. The intensity rule cut

1% from the replacement ratio for each additional 20 weeks of benefit

workers collected in the last five years. Repeated EI users’s replacement ration could be cut to a minimum 50% from the standard 55%.

Since there is a upper limit on the absolute amount of weekly EI benefit

payment at $413, the intensity rule only has impact on workers whose

weekly earning is less than $826.

High weekly earning workers are mostly affected by the clawback

rule, which could make EI collection less profitable or even undesirable

for them. According to the clawback rule, every EI user who isn’t a

repeated EI user, is required to repay 30% of their EI benefit, or 30%

of their net income above the threshold of $48, 750, whichever is less

through the taxation system. The repayment condition is different for

EI users with more than 20 weeks of benefit, they will need to make

repayment at a lower threshold of $39, 000 and a maximum of 50% to

100% of EI benefit could need to be repayed.

9EI

weekly benefit is the product of average weekly earnings and the applicable

replacement rate.

10From the taxation system.

8

KAILING SHEN

Since most non-seasonal workers could not plan on their EI collection, worker-side experience rating affects seasonal workers most. seasonal workers will have to go back to work every year about the same

time, otherwise they will lose their jobs. Their planning horizon is finite — one year. Under pre-reform system, it makes sense for seasonal

workers to work just year maximum weeks, which are the number of

employment weeks that they could use to collect EI benefit till the

start of their next job season. Each additional week of employment

beyond their year maximum weeks means one less week of EI benefit

collection. The nature of seasonal jobs and the pre-reform EI program

jointly provide incentive for seasonal workers not to work longer than

their year maximum weeks.

Post-reform, the incentives changed and each additional week of employment of high weekly earning seasonal workers means not only one

less week of EI benefit collection but also less repayment in subsequent

years. Indeed, in some situations, they might be better off not to collect

EI benefit even their job season hasn’t come yet. Although experience

rating was completely cancelled in May 2001, its impact is expected

to be substantial to high-income repeated users for even the first few

years 11.

11To

demonstrate the impact of clawback rule on high weekly income seasonal

workers, let’s assume a seasonal worker who typically work 28 weeks each year and

then collect 22 weeks of EI benefit in the rest of the year. If this worker normally

receives $2, 000 per week on his job, then he will get EI benefit at the maximum of

$413. Let’s call this option 1.

In this option, his EI benefit is $413×22 = $9, 086 in both years and his net annual

income before repayment is $20, 00×28+$9, 086 = $65, 086 in both years. The year

one clawback will take min{($65, 086 − $48, 750) × 30% = 4900, $9, 086 × 30% =

$2, 725} = $2, 725 away and left him with $62, 361. In year two, since he had

collected more than 20 weeks, he will face more severe clawback rule, which will

take min{($65, 086 − $39, 000) × 30% = 7825.8, $9, 086 × 50% = 4543} = $4543

away and left him with $60, 543.

In option two, suppose he only collect 19 weeks in each year. Then his EI benefit

is now $413×19 = $7, 847 in both years and his net annual income before repayment

is $20, 00 × 28 + $7, 847 = $63, 847 in both years. The year one clawback will take

min{($63, 847 − $48, 750) × 30% = $4, 529.1, $7, 847 × 30% = $2, 354.1} = $2, 354.1

away and left him with $61, 492.9. In year two, since he had collected less than 20

weeks, he will face same clawback rule as year one, which will left him with another

$61, 492.9.

In terms of total income in two years, option two will give him $81 more than

option one. The benefit from less severe clawback rule in option two will continue

to realize in year three and onward. Each year, he face more severe clawback rate

in option one than option two, thus he will get even less with choosing option one.

Moreover, with option two, he will have 3 weeks with no regular seasonal job, no

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

9

Seasonal workers are often regarded as having a higher potential to

improve their labour market attachment. Therefore, the four changes

could have a stronger impact on seasonal sector than on non-seasonal

sector.

In short, each of the four major changes in the regular EI benefit

program has its own targeted group and expected impacts upon that

group. At the same time, they also interact with each other, sometimes

offset each other. Jointly, they are meant to strength workers’ attachment to the labour market and discourage repeated usage of EI program. It is infeasible to separate individual impacts in such situation.

For example, study on the impact of increased entrance requirement

on new-entrants/re-entrants has to be considered together with easier

access to EI benefit due to the week to hour system change. Moreover,

there is reason to expect they have different impacts on seasonal and

non-seasonal sectors. Therefore, this study will take all the changes

in the 1996 EI reform as a package and study the net impact of this

reform on the distributions of employment spells and unemployment

spells for non-seasonal and seasonal sectors.

3. Data

Empirical studies on Canada’s EI program using Survey of Labour

Income Dynamics (SLID) have just started recently. Labour Market Activity Survey (LMAS), Canadian Out of Employment Panel

(COEP), and administrative data of EI program have been the major data sources used in EI studies in the literature.

In general, administrative data has more accurate EI collection information than survey data like SLID. As any other survey data, SLID

does not have as accurate EI information as administrative data. Researchers have to derive their own EI information based on EI rules

and labour market experience of the correspondents. But for all unemployed workers, only those made EI claims are included in the administrative data. After workers left EI payment, the administrative data

have no further information on their labour market activities unless

they come back to claim EI again. If an EI user has stopped collecting

EI benefit, we wouldn’t know whether the person, is still unemployed,

EI benefit. The opportunity cost of working is zero, so he has much more incentive

to work post year maximum week.

10

KAILING SHEN

becomes self-employed, has returned to school, or has left the country, etc. In this sense, EI administrative data provides incomplete and

selected information on the labour market transitions.

On the other hand, survey data usually has far more information

about each correspondents than administrative data. For example,

SLID not only has correspondents detailed job and job absence data, it

also has education, martial, mobility, family, and income data. Among

all survey data, SLID is the only one covers both pre- and post- 1996 EI

reform period. Therefore, SLID has strong potential in 1996 EI reform

evaluation.

I constructed eight groups of sample spells from SLID, employment

and unemployment spells in non-seasonal and seasonal sectors during

the pre-reform and post-reform periods. Given only paid employment is

EI insurable, these spells are constructed to focus on paid employment

labour force’ transitions between two states:

(1) employed with paid jobs only;

(2) unemployed due to loss of paid jobs.

My process of SLID data could be summarized in four steps: 1)construct person-specific observation windows; 2) create employment and

unemployment spells; 3) designate person, job, seasonality information

to each spell; 4) derive EI parameters for each week of each spell.

3.1. Construct person-specific observation windows. Although

this study focuses on paid-employment labour force and only studies

two states of the workers, employed with only paid jobs, and unemployed due to loss of paid jobs, each correspondents could experience

many other states during survey period. For example, schooling, retirement, self-employed, home-production, etc.

In order to make the final sample as accurate as possible, and at the

same time, representative of the experience of ‘ordinary’ workers who

are actively participating the paid employment labour market — the

group of workers that EI is meant to serve, person-specific observation

windows are constructed by excluding five types of periods from the sixyear survey panel time horizon. As a result, a correspondent could have

zero, one, or multiple observation windows, each of which is defined by

a start calender date and an end calender date.

These five types of excluded periods are:

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

11

(1) years out of the ten provinces of Canada or missing labour information;

(2) periods worked in non-paid jobs;

(3) from first year to last year of work disabled;

(4) from first month to last month of some schooling;

(5) from the date that a job spell censored due to inconsistency

follow-up information to panel end.

3.2. Create employment and unemployment spells. By construction, employment spells are spells of paid employment spells and unemployment spells are potential EI benefit collection spells that following

the paid employment spells. For each correspondent, each calender

date that he/she is recorded as working on paid jobs is flagged using

both job and job absences information. Employment spells are then

constructed using these flags,

According to Canada’s EI program, when unemployed workers’ applications for EI benefit are approved, they will not get EI payment for

the first 2 weeks of their unemployment spells. This is called waiting

period. For each EI user, the 3rd week of unemployment spell is actually his/her first week of EI benefit. Therefore, any two employment

spells separated by no more than 14 days are connected as one which

starts at the start date of the first spell and ends at the end date of

the second spell. On the other hand, unemployment spells following

employment spells are at least 15 days long. Therefore, the first 14

days, which aren’t informative, are deleted for estimation purpose.

Only fresh employment spells and unemployment spells started within

observation windows are selected. Fresh spells are selected mainly for

two technical reasons: 1) it is problematic to assume behaviour of ongoing spells while out of observation windows are the same as when

they are inside observation windows under duration dependence assumption. 2) It is impossible to derive EI data for ongoing spells at

the start of the panel because EI benefit duration calculation needs

minimum 52 weeks of previous labour market history, which means

any spells started within the first year of the panel could not be used

and they weren’t used in the estimation.

Each selected spell is further censored if its end date is beyond its

corresponding observation window’s end date. In this manner, the

study is focused on the majority of workforce who works on paid jobs

only while recognizing transitions into and out of this workforce.

12

KAILING SHEN

The sample scheme used here is ‘endogenous’ or ‘choice-based’ according to Lancaster and Imbens (1990) which examined how different

sampling schemes could affect the inference. Using the current sample

scheme, the sample spells are not representative for the whole population. Instead, they are representative of workers who experience

labour market transitions. In other words, these spells are weighted

according to workers’ probabilities of experience transitions between

employment and unemployment states. Workers who tend to have

more frequent transitions are weighted more and their behaviours have

more important impact on the results of this study. Those workers who

stay employed all the time are least represented in the results. This

sample scheme thus allow the results closer to the real composition of

EI users.

The sample weight could also be affect by the panel nature of SLID.

Although each panel consists of randomly selected individuals at the

start of the panel, the composition of the group of workers that experience labour market transitions could be changing over time if more

and more workers have found stable jobs and there aren’t enough new

entrants to the labour force. To prevent such composition-caused bias

in estimation, pre-reform and post-reform samples are selected from a

common time-frame relative to the panel they belong.

Specifically, I use both panels of currently available SLID in this

study. Pre-reform sample are those panel one (1993–1998) spells started

in the period from 1994 July, the time of a previous substantial EI

program change, to 1996 June, and post-reform are those panel two

(1996–2001) spells started in the period from 1997 July to 1999 June.

3.3. Designate person, job, seasonality information to each

spell. Personal characteristics, such as age, gender, martial status,

education, kids, etc, were matched with each spell given the year of

the spell. Then, only those spells with age in the range of [20, 54] are

selected.

To designate job property to each spell, a single most relevant job/job

absence was chosen for each spell even though it could contain multiple

jobs/job absences.

For any employment spell, among all jobs that started at the beginning of the spell, called start jobs, the one last the longest was chosen.

In case there are job absences ended at the beginning of an employment

spell, among the jobs corresponding to those job absences, the one that

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

13

started the earliest was chosen and its job property at the start of that

employment spell was used.

For any unemployment spells, among all jobs that ended at the beginning of the spell, called end jobs, the one last the longest was chosen.

In case there are job absences started at the beginning of an unemployment spell, the job absence that ended the latest was chosen and the

job property of its corresponding job before the start of that unemployment spell was used.

Seasonality of each spell is determined by the seasonality of the

job/job absence chosen for job properties. Seasonality of each job depends on the job ending reason. A job is seasonal if and only if it ended

due to seasonal reason. Seasonality of each job absence depends on the

job absence reason. A job absence is seasonal if and only if it started

due to seasonal reason.

As a result, seasonal employment spells are those employment spells

who started with a seasonal job which lasted the longest among all start

jobs, or started due to an ending of a seasonal job absences whose corresponding job has lasted the longest. Seasonal unemployment spells are

those unemployment spells who started because a seasonal job ended,

and this seasonal job is the longest one among all end jobs, or started

due to a seasonal job absence.

The choice made here regarding seasonality might be the simplest

one possible. In theory, such seasonality designation is problematic for

employment spells because most job’s seasonality depends on whether

they are censored. If censored, jobs are flagged as non-seasonal unless

they have a previous seasonal absence. For unemployment spells, since

all end jobs already ended, their seasonality are clear.

But in practice, the problem for employment spells’ seasonality is

much less severe. The pre-reform spells are those started within the

period from 1994 July to 1996 June in panel one. Only those employment spells whose start jobs didn’t end in December 1998 have the

seasonality flag problem. Given those jobs should be at least 2 and

half years long, they are most probably non-seasonal jobs rather than

seasonal jobs. Similarly, the post-reform spells are those started within

the period from 1997 July to 1999 June in panel two — exact the same

position and length as pre-reform group in panel one. The probability

of a seasonal job to last more than 2 and half years long is considered

to be negligible.

14

KAILING SHEN

Spell’s seasonality designation rule used here is very similar as in

Green and Sargent(1998) which also designate seasonality according to

job separation reason. It is obviously quite different in nature from

seasonality classifications often used to describe the extent of repeat

EI usage, as in EI Monitoring and Assessment report and Gray and

Sweetman (2001), where EI users’ seasonality depends on posterior

knowledge about labour market transitions pattern. Considering most

workers know whether their chosen jobs will end for seasonal reasons

or not, spells’ seasonality as defined in this study is effectively set a

priori, thus a proper explanatory for labour market transitions.

3.4. Derive EI information for each week of each spell. Derivation of EI variables for each week of each spell is necessary even though

SLID does allow identification of whether each worker has received EI

benefit in monthly term. Even if this information is in the desired

weekly term and there is reasonable accuracy in such posterior knowledge, it would be affected by actual take-up rates and still miss the

potential EI benefit duration available for each week employed and unemployed, which is critical to study how EI incentives affect labour

market transitions.

The contribution of each additional week to EI benefit is not necessarily the same because each employment spells could be formed by

several jobs and weekly hours of each job could vary over time. Therefore, I used weekly hours of every related job within each employment

spell to derive the EI employment accumulated at each week. For prereform spells, the EI employment is in terms of calender weeks, for

post-reform spells, hours.

For all employment spells, the number of EI benefit weeks that

worker could get if the spell ended at that week is then calculated week

by week using local EI unemployment rate used by the EI administration and applicable schedule. For each week in each employment spell,

I also calculated the applicable EI entrance requirement, EI year maximum flag, and EI maximum flag. These two flags signal the workers

have accumulated the maximum number of EI benefit weeks that are

useful for them. Seasonality matters in the employment spells estimation setup in the sense that EI year maximum flag is used for seasonal

spells only and EI maximum flag for non-seasonal spells only.

For seasonal workers, assuming they will have to return back to work

the same time of the year every year, then they only need enough EI

benefit to cover them till the start of next season. Therefore, when

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

15

the number of weeks already worked and the number of EI benefit

weeks accumulated reached 53, a seasonal worker is regarded as having

reached year maximum and EI year maximum flag is set to be 1 for

that week. Non-seasonal workers do not have 1 year planning horizon.

When the number of EI benefit weeks accumulated has reached maximum given the EI schedule, that non-seasonal worker is regarded as

having reached EI maximum week, therefore EI maximum flag is set

to be 1 for that week.

It should be point out that, at this point, special provisions of the

EI system for new-entrants/re-entrants, repeaters and renewals as considered in Kidd and Shannon (1996) are still to be incorporated in the

EI variable constructions.

Following Green and Sargent (1998), I then used these three timevarying EI variables to capture how EI incentives could affect the probability of employment separation.

For unemployment spells, the number of EI benefit weeks eligible

was derived first. Then following Ham and Rea (1987), for each week,

the number of EI benefit weeks left are calculated. Based on these

remaining EI weeks, several time-varying dummies are created to capture how the average level of the probability to leave unemployment

are related with the number of remaining weeks.

It has to be noted that workers’ local EI region is not readily available

in the original SLID data. To derive EI region, with special help from

SLID, I matched each worker’s corresponding end of year household’s

postal code with a conversion table kindly generated by HRDC. This

approach assume three things: 1)the worker didn’t change household;

2)that household didn’t move over the year; 3)postal code boundaries

remain the same over the year.

After these four steps, eight groups of spells are created for examination, employment and unemployment spells in non-seasonal and seasonal sectors during the pre-reform and post-reform periods. Workers

are studied only when they were active in the labour market. After all,

it is EI reform’s impact on these flows of workers that the evidence of

this study tries to evaluate. Different from conventional interpretation

of unemployment spells, the unemployment spells here are best interpreted as potential EI collection spells and used to capture workers’

re-employment process.

16

KAILING SHEN

3.5. Descriptives statistics. Descriptives statistics in Table 1 and 2

captured the composition variation among the eight groups of spells.

Among these groups, the most obvious difference in sample size and

composition happened is across seasonality groups, not across states

or periods groups, and the across seasonality differences are relatively

independent of the state and period combination. which shows the

comparability of pre-reform samples with post-reform samples.

Given any state and period combination, 20% of the sample are seasonal ones which, in general, have less female, less education, more

concentrated in agriculture and manufacture industries, less public industry cases, in smaller firms12, much higher proportion to have worked

for the same employer in previous jobs, a bit less union coverage rates,

and less immigrants. Such pattern reflected in the descriptive statistics

makes it reasonable to expect different impacts of 1996 EI reform on

labour market transitions across seasonality groups.

4. Econometric model

Spells are assumed to be generated in two steps: first, the discrete

proportional hazard model generates the true underlying distribution

of spells; and, second a heaping model taking account of measurement

error that might generate the observed distribution of spells. The measurement model in step two explicitly models the heaping effect, which

means, in this study, with respect to “a priori expectations about the

smoothness of the distribution”, the observed data shows “an abnormal concentration of duration at certain dates”— 15th and last day of

each month (Torelli and Trivellato (1993)).

4.1. Underlying model: discrete proportional hazard model.

Four related functions could represent the distribution of the length of

a spell, T : 1) probability density function (pdf), ft , gives the probability of a spell to be t weeks; 2) cumulative distribution function

(cdf), Ft , gives the probability of a spell to end at or before week t; 3)

complementary cumulative distribution function (ccdf), F t , gives the

probability of a spell to be more than t week long; and finally, 4) hazard

function (hf), ht , gives the probability of a spell to end at week t given

it is at least t − 1 week long.

12This

is measured by firm size, i.e., number of employees at all locations.

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

17

Given any one of them, the other three distributional functions are

determined as well. The mathematical definitions and relationships of

these four functions are as follows,

(4.1)

(4.2)

ft ≡ P rob{T = t} =

ht

if t = 1

Qt−1

ht · s=1 (1 − hs ) if t ∈ {2, 3, . . . }

Ft ≡ P rob{T ≤ t} = 1 −

t

Y

(1 − hs )

s=1

(4.3)

F t ≡ P rob{T > t} =

t

Y

(1 − hs )

s=1

(4.4)

ht ≡ P rob{T = t|T ≥ t − 1} = ft /(1 − Ft ) = ft /F t

The discrete hazard model I used in this study directly modelled ht

for each week of each spell. But after estimation was done, ccdf and

pdf as well as hazard function are used to analysis the distributional

impact of 1996 EI reform.

In the discrete hazard model, ∀t ∈ {1, 2, . . . , 50}, hazard rate for

spell i at week t, hi,t , is given by H(.) as follows,

(4.5) hi,t = H(xi,. , t; θ, β) ≡ exp(− exp(θt ) · exp(cxi · βcx + tvxi,t · βtvx ))

Therefore, the baseline hazard rate for week t is given by exp(− exp(θt )).

Set of covariates that remain the same value within each spell is cx. Set

of covariates that are allowed to change weekly is tvx. In both cases,

covariates for spell i at week t shifts the hazard rate proportionally

relative to the baseline while still in the range of [0, 1].

Among others, Meyer (1990), Green and Sargent (1998), Green and

Riddell (2000), also chose such proportional hazard model to study EI’s

impacts on labour market transitions. The advantage of this model is

that time-varying EI variables could be entered into the model easily.

But different from above studies where the baseline, θ, was estimated

non-parametric using dummy variables, I imposed a parametric form on

the baseline. The baseline vector θ captures the duration dependency

18

KAILING SHEN

of the hazard function. By imposing parametric form on θ, I am able to

get explicit results on the slope and curvature of this baseline. Since the

measurement error will be taken care of in the second step of modelling,

it is reasonable to believe that the movement of the true behaviour

hazards from week to week follows some smooth pattern. Moreover,

parametric baseline specification is a more parsimonious setup.

The conventional parametric baseline specification on θt is to use

direct polynomial approximation approach, or “direct approach” as

called in Cooper (1972) which strongly recommended “Lagrangian interpolation polynomials” over “direct approach”. Cooper(1972) compared these two approaches and demonstrated their “algebraic equivalence and computational differences”, where it was shown that “the

direct approach can be hampered by multicollinearity in the artificial

variables created for computational purpose.” Following his suggestion, I use the ‘Lagrangian interpolation polynomials” in the baseline

specification of this study. The θt in (4.5) is defined as follows,

(4.6)

A

P

−1 α

θ1

θ(α, 1)

1 1 1 12

1

2

1

1

1

α1

θ2 θ(α, 2) 1 21 22

1

2

. =

1

26

26

α2

=

×

×

..

..

. . . . . . . . .

.

1

2

1 50 50

α3

1 501 502

θ50

θ(α, 50)

The only difference from conventional direct polynomial approximation is that I add matrix P in the transformation from α to θ. After

estimation, the derived baseline θ̂ should be the same whether direct

polynomial approximation is used or Lagrangian interpolation polynomials is used.

Using (4.6), (4.5) could be rewritten in terms of (α, βcx, βtvx ) as

(4.7)

hi,t = G(xi,. , t; α, βcx, βtvx ) ≡ exp(− exp(θ(α, t)·exp(cxi ·βcx +tvxi,t ·βtvx ))

Having specified hazard function hi,t , the underlying behaviour distribution for spell i is then fully determined. fi,t , Fi,t , F i,t could be

derived from hi,t using (4.1), (4.2) and (4.3) respectively.

4.2. Measurement model: heaping at certain dates. The measurement model then translates the true underlying distribution of

spells to observed distribution assuming a specific form of heaping

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

19

at 15th and last day of each month. The heaping assumed in this

study could be interpreted as a result of correspondents’ rounding-off

behaviour in , or institutional, for example, bi-weekly/monthly salary

system.

Given EI data is organized in weekly unit, heaping caused spikes in

hazard function could potentially obscure the “true” EI spikes. For

example, suppose a worker leaves employment as he has just reached

year maximum EI week in the underlying data generation process. But

due to heaping at monthly term, he is observed to leave at the end of

month which contains that year maximum EI week. The true behaviour

spike at year maximum EI week will not be observed unless we explicitly

model heaping effect.

Let γ1 be the probability of spells ending only been observed in the

week containing 15th and last day of the month, γ2 be the probability

of spells ending only been observed in the week containing last day of

the month. Then γ0 = 1 − γ1 − γ2 is the probability that spells ending

been reported in the week they ended.

Generally, heaping could happen in two directions, forward to the

next neighboring heaping weeks, and backward to the previous neighboring heaping weeks. This paper assumed forward heaping only.

Given fi,t from (??f1))and (γ0 , γ1 , γ2 )13, the probability density function of observed distribution of spell i, fei,t , is then given as follows,

(4.8)

fei,t = γ0 · fi,t + γ1 ·

X

s∈SB(t)

fi,s + γ2 ·

X

fi,s

s∈SM (t)

Where SM (t) is empty for all t except if week t contains the last

day of a month. If SM (t) is non-empty, then it is equal to the set of

weeks no later than week t and in the same calender month as week t.

For example, assume week 5, 11, 15, .. in a spell are the only weeks that

have the last of a month, then SM (1) = SM (2) = SM (3) = SM (4) =

∅, SM (5) = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}, SM (6) = SM (7) = SM (8) = SM (9) =

SM (10) = ∅, SM (11) = {6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11}, SM (12) = SM (13) = SM (14) =

∅, SM (15) = {12, 13, 14, 15}, . . .

SB(t) is similarly defined where heaping effect takes place in both

15th of the month and last day of the month. Again, using above example, weeks that have 15th of a month are week 3, 8, 13, .., then SB(1) =

13By

construction, (γ0 , γ1 , γ2 ) have to be in the range of [0, 1].

20

KAILING SHEN

SB(2) = ∅, SM (3) = {1, 2, 3}, SB(4) = ∅, SM (5) = {4, 5}, SB(6) =

SB(7) = ∅, SB(8) = {6, 7, 8}, . . .

The identification of heaping probabilities (γ0 , γ1 , γ2 ) is thus from

the smooth parametric baseline hazard function and variations in the

calendar properties of each spell, that is variations in SM (t) and SB(t).

4.3. Loglikelihood function. Given the pdf function of observed distribution of spells, fe(i, t), the contribution to the loglikelihood function

of observing spell i is then,

(4.9)

l(i, t) = fe(i, t)δi · (1 −

t

X

s=1

fe(i, s))1−δi

Where δi = 1 if spell i is complete and 0 if censored.

Obviously, if set {γ1 , γ2 } be zeros, the model will be the traditional

hazard model. In this sense, the combined model used here is more

flexible. Further, given most EI impact is captured using time-varying

covariates, this approach will allow more clear identification of EI spikes

from the calender heaping spikes.

5. Estimation results

In this part, the impacts of 1996 EI reform is discussed using the

estimation results directly. It is shown that the 1996 EI reform’s impacts on labour market transitions are different across seasonal and

non-seasonal sectors as well as different across different worker and job

types. Several patterns of the labour market transitions in the first 50

weeks are also shown to remain the same during the period.

In all estimation, a common omitted group is used for comparability

reason. They are workers who are male, married, household heads,

high school educated, in management industry, with firm less than 20

employees, have not worked for their current employers in previous jobs,

not covered by union of collective bargaining, no kids, not immigrants,

36 year old, with $13 hourly wage, local EI region’s unemployment rate

is 7%.

This omitted group looks like a mixture of typical seasonal workers and typical non-seasonal workers. The impacts of 1996 EI reform on this omitted group, as reflected by baseline hazard rates shift

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

21

post-reform, might not be representative of the sample, whether nonseasonal or seasonal. Therefore, simulation results are presented in

later section as well.

Estimated coefficients are presented in four tables (3-6). All spells

are censored at week 50 in estimations since EI incentives only explicitly change in the first year of spells. In each estimation, the set of

time-varying covariates in each estimation are used to capture EI effects only, while the set of time-constant covariates in each estimation

are used to capture worker and job characteristics’ impacts on spells’

distribution– winners and losers of the reform as well as sensitivity to

local unemployment rate. The estimated coefficients of these two sets

are thus summarized in different tables. Definitions of most of the variables used in the estimation are self-evident, except one, the EI region

monthly unemployment rate, which is in the raw form derived from

Labour Force Survey. Relative to the 3-month moving average seasonally adjusted unemployment rate used by EI administration, this

raw form of unemployment rate is a better control for macroeconomic

conditions with less correlation with EI variables.14

Assuming the omitted group and 12% local EI administrative unemployment rate, the impacts of EI incentives on hazard rates of prereform and post-reform employment spells are illustrated in figure 1.

Assuming the omitted group and 24 weeks of EI benefit available, the

impacts of EI incentives on hazard rates of pre-reform and post-reform

unemployment spells are illustrated in figure 2.

As another way of showing the estimated coefficients, F 50 for default types of spells and marginal impact on F 50 by changing covariate

are included in table 7 to 10. The results are mostly consistent with

estimated coefficients but in a more intuitive manner.

5.1. Non-seasonal Employment spells. For employment spells, positive coefficients will means higher probability of employment separation. The major impacts of 1996 EI reform on employment stability

(see table 3 and 4) are:

14The

unemployment rate that I derived for estimation is just the raw number

which equals to the ratio of number of unemployed worker over total number of

workers in the labour force. The administrative rate is problematic as control for

macroeconomic conditions as it is correlated with workers’ EI incentives under VER

and, moreover, the seasonal fluctuation of labour market condition is smoothed out

in the administrative rate.

22

KAILING SHEN

5.1.1. winners. The group of non-seasonal workers whose employment

stability improved more than the omitted group are those who are

single, not household head, less than high school educated, employed

in service and public industries, employed by firms whose sizes are in

[20, 100) and [100, 500) categories, worked for the employer previously,

had pre-school kids.

5.1.2. losers. The group of non-seasonal workers whose employment

stability improved less than the omitted group are those who worked

in manufacture industry, immigrants.

5.1.3. sensitivity to local labour market. Moreover, employment stability in the first 50 weeks became more sensitive to local unemployment

rate after the reform. As table 7 shows, probability for non-seasonal

employment spell to last more than 50 weeks, 4F 50 , will be 2.1% lower

for each 1% increase in local EI region’s unemployment rate after the

reform. This inverse correlation between employment stability and unemployment rate could be interpreted as showing “negative cyclical

impact on job match quality” as Bowlus(1993) has found using the

National Longitudinal Survey of Youth data. But this change could

also be caused by 1996 EI reform.

5.1.4. EI impacts. According to table 4, the current estimation didn’t

find any statistically significant EI effect within pre- or post-reform

group for non-seasonal employment spells. Any seeming impacts showed

in figure 1(a) and 1(b) are not statistically significant.

But this isn’t a complete proof for no impacts of 1996 EI reform on

non-seasonal employment spells. Although raw unemployment rate is

used in my study to control for macroeconomic conditions, the changes

in labour market transitions after the reform as shown in this study

could still be partially driven by macroeconomic conditions. Unemployment rate is only one commonly used measure of macroeconomic

conditions which could affect labour market transitions in many dimensions linearly or non-linearly. For example, Baker (1992) suggests

the interaction between worker type and hazard rate could be affected

by business cycle. If this is true, then the winners and losers in nonseasonal sector’s employment spells as discussed earlier could be caused

by the 1996 EI reform as well as the overall improvement of macroeconomic conditions. Another study using periods with same EI program

but different macroeconomic condition is then needed to complement

the current study.

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

23

5.2. Seasonal Employment spells.

5.2.1. winners. The group of seasonal workers whose employment stability improved more than the omitted group are those who are employed in agriculture, manufacture industries, employed by firms whose

sizes are above 20, immigrants.

5.2.2. losers. The group of seasonal workers whose employment stability improved less than the omitted group are those who worked for the

employer previously.

5.2.3. sensitivity to local labour market. Unlike non-seasonal case, the

sensibility of employment stability in the first 50 weeks with regard to

local unemployment rate didn’t change after the 1996 EI reform.

5.2.4. EI impacts. According to table 4, EI effects are statistically significant in both pre- and post- reform for seasonal employment spells.

And the EI effects changed over time (figure 1(c), 1(d)). Increasingly

seasonal workers are working beyond year maximum weeks now.

Pre-reform, seasonal workers tend to postpone leaving their employment before they could get EI benefit, which is consistent with theoretical prediction on EI entrance requirement effect. As shown in figure

1.c, employment hazard rate — conditional probability to exit employment state — is below the baseline before week of entrance requirement.

Furthermore, the closer to entrance requirement week from the left, the

larger the difference from the baseline. Then, once entrance requirement is met, the hazard rate jump back to the baseline quickly. Once

they passed the entrance requirement week, their employment separation process will no long be affected by EI incentives except at the year

maximum week. There is a significant spike at the year maximum week

that signals that seasonal workers did have tendency to leave employment once they have accumulated enough EI benefit to collect till their

next job season.

Post-reform, EI entrance requirement effect was still significant but

the sharp decrease of hazard rate just before entrance week disappeared

and the magnitude is smaller in weeks before entrance weeks as well.

The most dramatic change in EI effects for seasonal employment spells

happened is the way year maximum week affect the hazard rate. After

the reform, most workers will postpone their employment separation

until they have reached year maximum weeks. This phenomenon is

24

KAILING SHEN

absence in pre-reform period. Moreover, the sharp increase of hazard

rate in year maximum week disappeared post reform.

Overall, the shape of hazard function with EI incentives incorporated changed dramatically after the reform. One major factor behind

such change could be the introduction of experience rating which effectively force seasonal workers’ planning horizon to be five year long

and take away some of the disincentives of working long season. If

this hypothesis is proved, then the change in seasonal workers’ employment behaviour demonstrates the tailoring behaviour did exist in the

pre-reform period.

5.3. Non-seasonal unemployment spells. For unemployment spells,

positive coefficients mean higher probability of re-employment. According to table 5 and 6, the major changes in re-employment process

given seasonality after the 1996 EI reform are:

5.3.1. winners. The group of non-seasonal workers whose re-employment

process speed increased more than the omitted group are those who are

not household head.

5.3.2. losers. The group of non-seasonal workers whose re-employment

process speed increased less than the omitted group are those who are

female, in the service industry. Overall most of the covariates do not

affect re-employment speed whether pre-reform or post-reform.

This is different from employment separation process, where a much

larger set of covariates affect the process significantly.

5.3.3. sensitivity to local labour market. Also different from employment separation process, in non-seasonal sector, re-employment process

in the first 50 weeks is not statistically correlated with local unemployment rate after the reform.

5.3.4. EI impacts: EI eligibility. According to table 6, pre-reform in

non-seasonal sector, re-employment process is much quicker for workers

who have no EI benefit then for those who have EI benefit pre-reform.

After the reform, the difference in re-employment speed caused by EI

benefit eligibility disappeared.

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

25

5.3.5. EI impacts: EI benefit weeks. The current estimation didn’t find

any statistically significant EI effect within pre- or post-reform group

for non-seasonal employment spells. Any seeming impacts showed in

figure 2(a) and 2(b) are not statistically significant.

5.4. Seasonal unemployment spells.

5.4.1. winners and losers. Most types of seasonal workers’ re-employment

process speed increased less than the omitted group, except for single,

union covered workers. Before reform, re-employment process speed

was not affected by age, but after the reform, age is positively correlated

with re-employment process speed — older workers get re-employed

faster now. This is different form the non-seasonal case, where age is

negatively correlated with re-employment process speed whether prereform or post-reform.

5.4.2. EI impacts: EI eligibility. According to table 6, pre-reform in

seasonal sector, re-employment process is much slower for workers who

have no EI benefit then for those who have EI benefit pre-reform. After

the reform, the difference in re-employment speed caused by EI benefit

eligibility disappeared.

5.4.3. EI impacts: EI benefit weeks. But the pattern EI benefit weeks

affect re-employment process changed dramatically after the reform.

Another peak in hazard function emerged.

While pre-reform, a substantial proportion of seasonal workers will

just exhaust their EI benefit before return back to work, which is consistent with seasonal workers’ tendency to collect just year maximum

weeks when employed in the pre-reform period.

After the reform, a substantial proportion of seasonal workers will

leave at least 5 weeks of benefit unused when they return back to

work. The emergence of this second, larger peak might be a result of

the introduction of worker-side experience rating.

5.5. Estimated heaping probabilities. The estimated coefficients

show statistically significant heaping effect. Probability for ending of

employment spells to be reported in monthly term is estimated to be

above 30% and probability for employment spells to be reported in biweekly term is estimated to be 10% to 27%. This means less than half

of ending of employment spell were reported in weekly term. But with

26

KAILING SHEN

help of heaping effect measure model, I was still able to capture the EI

effect in weekly term.

It is interesting to notice that the estimated probability for ending

of unemployment spells to be reported in monthly term is zero, which

could be explained as workers were much more exact in reporting the

start of their jobs then reporting the end of their jobs. Further, the

estimated probability for ending of unemployment spells to be reported

in bi-weekly term is substantially higher in seasonal sector than in nonseasonal sector.

5.6. Estimated duration dependency by state and seasonality.

Not only 1996 EI reform have different impacts on labour market transitions across seasonality groups, the estimated duration dependencies15

of hazard function turned out to be very different across seasonality

groups as well, as illustrated in the baselines of figure 1 and 2.

There is little duration dependency in non-seasonal sector’s employment separation process but non-seasonal sector’s re-employment process still shows considerable duration dependency. The longer some

one unemployed, the lower his/her chance of getting re-employed.

For seasonal spells, the duration dependency shows obvious peak

in the middle of the study period which might due to the nature of

seasonal jobs.

On the other hand, we could not then conclude the hazard is higher

post-reform for overall even though the baseline hazard function shifted

up for the omitted group after the reform in non-seasonal employment

and unemployment spells. The composition of spells have to be considered.

6. Simulation using actual spells

Simulation using actual spells is mainly to understand how 1996

EI reform affected labour market transitions to the observed samples,

taking account of their composition in terms of worker and job. Such

results are especially important when the omitted group isn’t representative.

15As

mentioned in Lancaster(1989), estimated duration dependency will be affected by to what extend heterogeneity of the sample is accounted for.

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

27

6.1. simulation design. The observed impacts of 1996 EI reform on

pre-reform spells could be decomposed into two parts:

1. The true impacts of 1996 EI reform given pre-reform spells, which

could be measured by comparing simulated distributions of pre-reform

sample’s worker and job types using pre-reform set of coefficients,

1

1

2

2

(α1 , βcx

, βtvx

) to post-reform set of coefficients, (α2 , βcx

, βtvx

).

2. The change due to worker and job types composition change,

which could be measured by comparing simulated distributions of prereform sample’s worker and job types with post-reform sample’s worker

and job types using a common set of coefficients, pre-reform or postreform.

Average magnitude of each decomposed part of the impacts is captured in the differences of the weighted mean of pdf,f t , and ccdf, F t of

simulated distributions (figure 3 and 4).

The winners and losers in each decomposed part of the impacts of

1996 EI reform is then analyzed using OLS(table 11 to 14), which used

F 50 from two sets of F t as independent variables and using pre-reform

sample worker and job types x1 as explanatory variables. The two sets

of F t comes from simulated distributions of using pre-reform sample

spells’ worker and job types and two different sets of coefficients: prereform and post-reform. As a result, I got two sets of OLS coefficients,

b1 and b2 . Using these two OLS coefficients and means of pre-reform

and post-reform sample worker and job types variables, x̄1 and x̄2 , I

then captured the winners and losers in each steps of decomposition

(table 11-14).

6.2. simulation results.

6.2.1. Non-seasonal employment spells. After the reform, entrance requirement effect of EI disappeared which lead to the disappearance of

the peak in the pdf function. The observed increase in non-seasonal sector’s employment stability, 4F 50 = 7.47% is mainly caused by more

stable employment of workers, who are single, not household head,

union or collective bargaining coverage, which offset the less stable employment of workers, who are in the manufacture industry, female and

have post-secondary education.

28

KAILING SHEN

6.2.2. Seasonal employment spells. After the reform, a substantial workers in the seasonal sector choose to work more than their year maximum week. The obvious peak in the pre-reform seasonal employment

spells’ pdf function thus became considerably weaker. This change is

the major factor that lead to more stable employment post-reform in

the seasonal sector, 4F 50 = 5.99%.

6.2.3. Non-seasonal unemployment spells. After the reform, the disappearing of EI benefit exhaustion effect is the major factor that lead to a

quick re-employment process in non-seasonal sector, 4F 50 = −4.24%.

6.2.4. Seasonal unemployment spells. Seasonal workers’ re-employment

process became quick after the reform, 4F 50 = −3, 43%, mainly due

to the fact that after the reform, a substantial seasonal workers got reemployed when they still have some remaining EI benefit uncollected.

In short, the 1996 EI reform did have positive impacts on enforcing

workers labour market attachment in seasonal and non-seasonal sectors after controlling for composition change. At the same time, this

reform’s impacts are distributed unevenly across worker and job types.

7. Related studies, future works and conclude

This study is related to at least three areas in the literature. First,

empirical EI studies as surveyed in Welch (1977) and more recently

Holmlund (1997); Second, hazard model studies. Besides those already mentioned earlier, some important research in this area are Lancaster (1990), Heckman and Singer (1984), and Van den Berg (2000);

and third, economic theoretical models on labour market transitions.

Earlier studies in this area include Burdett (1978), Mortensen (1977),

Jovanovic (1984). There are also many other studies related to this

study, but it is beyond this paper to give a proper review of all the

studies that related to my study in a broader sense.

One group of studies that are closely related to this paper are those

which evaluate 1996 EI reform’s impacts from other directions. Their

results are generally consistent with findings of this study. For example, Green and Riddell (2000) studies 1996 EI reform’s impacts on

employment spells caused by week to hour system. They found that

seasonal employment spells didn’t become shorter after the reform if

comparing spells ended during first 3 quarters of 1997 with first 3 quarters of 1996. They also found non-seasonal employment spells weren’t

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

29

affected much by EI program either pre-reform or post-reform. Fortin

and Audenrode (2000) found some evidence of worker-side experience

rating on workers’ unemployment spells.

Based on these studies, there are several directions that this current study could be expanded. For example, in this current study

the multiple spells nature of the sample is not modelled, each spell’s

seasonality is treated as fixed, lagged duration dependence is ignored.

Extra elements could be added to the current econometric model to

accommodate a richer data generation process.

In summary, this current study shows the impacts of 1996 EI reform

on employment and unemployment spells are related and its impacts

differ between seasonal and non-seasonal spells, between different workers and job types. After controlling for composition change, macroeconomic condition change, this study found some evidence that the 1996

EI reform might have discouraged tailoring behaviour and on average,

the probability for an employment spell to last more than 50 weeks

increased and the probability for an unemployment spell to last more

than 50 weeks decreased after the reform, both in non-seasonal as well

as seasonal sectors. This study also revealed the impact of the 1996 EI

reform distributed unevenly across different worker and job types.

30

KAILING SHEN

References

Baker, M., M. Corak, and A. Heisz (1998): “The Labour Market Dynamics of

Unemployment Rates in Canada and the United States,” Canadian Public Policy,

pp. 72–89.

Baker, M., and S. Rea, Jr. (1998): “Employment Spells and Unemployment

Insurance Eligibility Requirements,” Review of Economics and Statistics, pp. 80–

94.

Bowlus, A. J. (1993): “Job Match Quality over the Business Cycle,” in Panel

Data and Labour Market Dynamics, ed. by H. Bunzel, P. Jensen, and N. Westergård-Nielsen, pp. 21–41. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., North-Holland.

Burdett, K. (1978): “A Theory of Employee Job Search and Quit Rates,” American Economic Review, pp. 212–220.

Clark, K. B., and L. H. Summers (1982): “Unemployment Insurance and

Labor Market Transitions,” in Workers, Jobs, and Inflation, ed. by M. N. Baily,

pp. 279–318. Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.

Cooper, J. P. (1972): “Two Approaches to Polynomial Distributed Lag Estimation: An expository Note and Comment,” American Statistician, pp. 32–35.

Fortin, P., and V. Audenrode, Marc (2000): “The impact of worker’s experience rating on unemployed workers,” Prepared for: Stategic Evaluation and Monotoring, Evaluation and Data Development, Stategic Policy, Human Resources Development Canada.

Gray, D., and A. Sweetman (2001): “A Typology Analysis of the Users of

Canada’s Unemployment Insurance System:Incidence and Seasonality Measures,”

in Essays on the Repeat Use of Unemployment Insurance, ed. by S. Schwartz, and

A. Aydemir, pp. 15—61. Social Research and Demonstration Corporation.

Green, D. A., and W. C. Riddell (1993): “The Economic Effects of Unemployment Insurance in Canada: An Empirical Analysis of UI Disentitlement,” Journal

of Labor Economics, pp. S96–S147, Part 2: U.S. and Canada Income Maintenance

Programs.

(1997): “Qualifying for Unemployment Insurance: An Empirical Analysis,” Economic Journal, pp. 67–84.

(2000): “The Effects of the Shift to an Hours-Based Entrance Requirement,” Prepared for: Stategic Evaluation and Monotoring, Evaluation and Data

Development, Stategic Policy, Human Resources Development Canada.

Green, D. A., and T. C. Sargent (1998): “Unemployment Insurance and Job

Durations: Seasonal and Non-Seasonal Jobs,” Canadian Journal of Economics,

pp. 247–278.

Ham, J. C., and S. Rea, Jr. (1987): “Unemployment Insurance and Male Unemployment Duration in Canada,” Journal of Labor Economics, pp. 325–353.

Heckman, J. J., and B. Singer (1984): “A Method for Minimizing the Impact of Distributional Assumptions in Econometric Models for Duration Data,”

Econometrica, pp. 271–320.

Holmlund, B. (1998): “Unemployment Insurance in Theory and Practice,” Scandinavian Journal of Economics, pp. 113–141.

Jones, S. R. g., and W. C. Riddell (1995): “The Measurement of Labour

Force Dynamics with Longitudinal Data: The Labour Market Activity Survey

Filter,” Journal of Labor Economics, pp. 351–385.

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

31

Jovanovic, B. (1984): “Matching, Turnover, and Unemployment,” Journal of

Political Economy, pp. 108–122.

Kidd, M., and M. Shannon (1996): “An Empirical Analysis of Recent Legislative Changes to Unemployment Insurance: The Effects of Bill C-21 and the

1994 Budget,” The Canadian Journal of Economics, 29(special issue: Part 1),

S12—S16.

Lancaster, T. (1990): The Econometric Analysis of Transition Data. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge.

Lancaster, T., and G. Imbens (1990): “Choice-based sampling of dynamic populations,” in Panel Data and Labour Market Studies, ed. by J. Hartog, G. Ridder,

and J. Theeuwes, pp. 21–43. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., North-Holland.

Lemieux, T., and W. B. MacLeod (2000): “Supply Side Hysteresis: the Case

of the Canadian Unemployment Insurance System,” Journal of Public Economics,

pp. 139–170.

Meyer, B. D. (1990): “Unemployment Insurance and Unemployment Spells,”

Econometrica, pp. 757–782.

Mortensen, D. T. (1977): “Unemployment Insurance and Job Search Decisions,”

Industrial and Labor Relations Review, pp. 505–517.

Torelli, N., and U. Trivellato (1993): “Data Inaccuracies and Sampling

Plan in a Model of Unemployment Duration,” in Panel Data and Labour Market

Dynamics, ed. by H. Bunzel, P. Jensen, and N. Westergård-Nielsen, pp. 171–188.

Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., North-Holland.

van den Berg, G. J. (2000): “Duration Models: Specification, Identification,

and Multiple Durations,” in Handbook of Econometrics, ed. by J. J. Heckman,

and E. Leamer, 5. North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Welch, F. (1976): “What Have We Learned from Empirical Studies of Unemployment Insurance?,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, pp. 451–461.

32

KAILING SHEN

List of Tables

1 Descriptive statistics for employment spells

2 Descriptive statistics for unemployment spells

3 Estimators for employment spells: Non-EI effects

4 Estimators for employment spells: EI effects

5 Estimators for unemployment spells: Non-EI effects

6 Estimators for unemployment spells: EI effects

7 simualted probability for employment spells: non EI effects

8 simualted probability for employment spells: EI effects

9 simualted probability for unemployment spells: non EI effects

10 simualted probability for unemployment spells: EI effects

11 Decomposition of 4F 50 using OLS: non-seasonal employment

spells

12 Decomposition of 4F 50 using OLS: seasonal employment spells

13 Decomposition of 4F 50 using OLS: non-seasonal unemployment

spells

14 Decomposition of 4F 50 using OLS: seasonal unemployment

spells

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

List of Figures

1 Estimated impacts of EI parameters on hazard functions of

employment spells

2 Estimated impacts of EI parameters on hazard functions of

unemployment spells

3 Simulated pdf function ft

4 Simulated ccdf function F t

47

48

49

50

EI REFORM AND LABOUR MARKET TRANSITIONS

33

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for employment spells

number of spells

female

single

not household head

less than high school

high school

post-secondary

university or above

agriculture

manufacture

management

service industry

public industry

service industry

firm size [1,20)

firm size [20,100)

firm size [100,500)

firm size [500,+∞)

worked for the employer previously

union or collective

bargaining coverage

present of pre-school

kids

present of school-age

kids

present of young

adult kids

immigrant

age

aStandard

Employment spells