Document 10819602

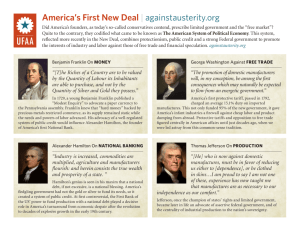

advertisement