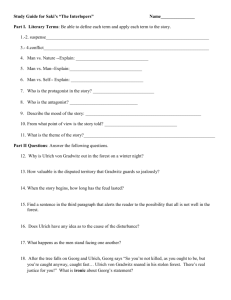

The Garden of Love

advertisement