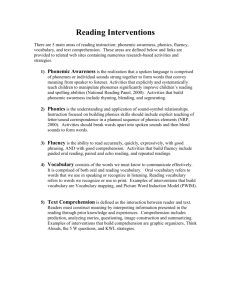

Put Reading First The Research Building Blocks For Teaching

advertisement