Review of Child and Adolescent Refugee Mental Health White Paper from the

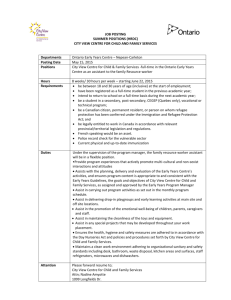

advertisement