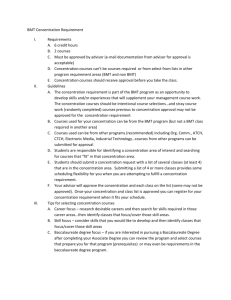

MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change

advertisement