Predictors of compliance with a home-based exercise program added

advertisement

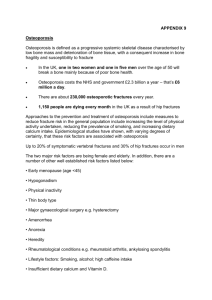

Osteoporos Int (2005) 16: 325–331 DOI 10.1007/s00198-004-1697-z O R I GI N A L A R T IC L E Predictors of compliance with a home-based exercise program added to usual medical care in preventing postmenopausal osteoporosis: an 18-month prospective study M.A. Mayoux-Benhamou Æ C. Roux Æ A. Perraud J. Fermanian Æ H. Rahali-Kachlouf Æ M. Revel Received: 1 December 2003 / Accepted: 15 June 2004 / Published online: 29 July 2004 International Osteoporosis Foundation and National Osteoporosis Foundation 2004 Abstract This prospective 18-month study was designed to assess long-term compliance with a program of exercise aimed to prevent osteoporosis after an educational intervention and to uncover determinants of compliance. A total of 135 postmenopausal women were recruited by flyers or instructed by their physicians to participate in an educational session added to usual medical care. After a baseline visit and dual-energy Xray absorptiometry, volunteers participated in a 1-day educational session consisting of a lecture and discussion on guidelines for appropriate physical activity and training in a home-based exercise program taught by a physical therapist. Scheduled follow-up visits were 1, 6, and 18 months after the educational session. Compliance with the exercise program was defined as an exercise practice rate 50% or greater than the prescribed M.A. Mayoux-Benhamou Æ H. Rahali-Kachlouf Æ M. Revel Rehabilitation Department, Cochin Hospital, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, René Descartes University, F-75014 Paris Cedex, France C. Roux Rheumatology Department, Hôpital Cochin, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, René Descartes University, F-75014 Paris Cedex, France A. Perraud National School of Statistics and Economic Administration (ENSAE), F-92245 Malakoff Cedex, France J. Fermanian Statistics Laboratory, Necker Hospital, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, René Descartes University, F-75015 Paris Cedex, France M.A. Mayoux-Benhamou (&) Service de Rééducation, Hôpital Cochin, 27 rue du Faubourg Saint Jacques, Pavillon Hardy, F-75014 Paris, France E-mail: anne.mayoux-benhamou@cch.ap-hop-paris.fr Tel.: +33-1-58412543 Fax: +33-1-58412545 training. The 18-month compliance rate was 17.8% (24/ 135). The main reason for withdrawal from the program was lack of motivation. Two variables predicted compliance: contraindication for hormone replacement therapy (odds ratio [OR] = 0.13; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.04 to 0.46) and general physical function scores from an SF-36 questionnaire (OR=1.26; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.5). To a lesser extent, osteoporosis risk, defined as a femoral T-score £)2.5, predicted compliance (OR=0.34; 95% CI, 0.10 to 1.16). Despite the addition of an educational session to usual medical care to inform participants about the benefits of exercise, only a minority of postmenopausal women adhered to a home-based exercise program after 18 months. Keywords Compliance Æ Determinants Æ Education Æ Exercise Æ Osteoporosis Æ Quality of life Introduction Osteoporosis is an increasing health care concern worldwide with the aging of the population [1]. This disease is multifactorial, and the dominant factor affecting bone metabolism in postmenopausal women is the decline in estrogen secretion. Other factors such as decreased physical activity [2] have been identified. Besides pharmacological interventions such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), physical activity [3] is commonly recommended for preventing osteoporosis and may be synergistic with estrogen level [4]. Therefore, prophylactic and therapeutic regimens may also include nonpharmacological interventions such as patient education to promote the long-term adoption of adequate lifestyle changes in postmenopausal women. However, these interventions are rarely used [5, 6, 7, 8]. Unfortunately, in osteoporosis, as in other chronic diseases, long-term compliance is poor [9]. An extensive search of Medline for osteoporosis exercise therapy revealed 326 studies of long-term exercise compliance in clinical trials [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] but none on exercise compliance in postmenopausal women in usual medical care or identification of its predictors. The aim of this prospective study was to assess compliance with long-term, home-based exercise and to identify the predictive factors of compliance in postmenopausal women 18 months after a 1-day educational intervention was added to usual medical care. nized into groups of 12 for the session, which included a lecture and a discussion. The lecture provided knowledge about osteoporosis symptoms, management, and appropriate preventive lifestyle behaviors. It focused especially on guidelines for practicing adequate physical activity. The discussion aimed to enhance positive attitudes and beliefs related to exercise. Then the participants were split into groups of four to learn the exercise program. Home-based exercise program Methods Subjects The Rehabilitation Department of the Institute of Rheumatology at Cochin Hospital in Paris has advocated an educational session addressing exercise in preventing osteoporosis in postmenopausal women since 1994. Outpatients of the institute were either informed by flyers or instructed by their physicians to participate in this educational session. Recruitment lasted from March 1999 to March 2000. To participate in the study, women had to be 70 years of age or younger, to have ceased the menses for at least 1 year, and had the physical ability for the selected training. Patients were excluded if they had a clinical history of a vertebral fracture or any previous general health conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or respiratory failure that made health recommendations inappropriate. Baseline evaluation The women had a baseline medical visit and underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). At the medical visit, data were collected on previous medical history, risk factors of osteoporosis, and lifestyle behaviors. Each woman completed an SF-36 questionnaire [16] and a Baecke questionnaire [17]. The SF-36 questionnaire assesses quality of life and measures health across three dimensions (functional status, well-being, and overall evaluation of health) with eight domains (such as physical functioning, vitality, social functioning, or mental health). One additional item measures health transition. The Baecke questionnaire assesses usual physical activity and measures habitual occupational and leisure-time (sport and nonsport) physical activity. Both questionnaires are validated in French [18, 19]. Lumbar and femoral DXA (Hologic QDR 1000; Hologic, Waltham, MA, USA) was performed on the same day, and T-scores were calculated. Results were given raw, without comments, to the participants. Educational session The 1-day educational session occurred within the 2 weeks after the baseline visit. Participants were orga- The daily exercise program included four exercises to reinforce hip flexor (especially iliopsoas), hip abductor (especially gluteus medius), erector spinae, and pronator muscles. The exercises, except those for erector spinae muscles, were performed with use of dumbbells and were divided into sets of 10 submaximal repetitions. The program included 30 repetitions of spine extension, 50 repetitions of flexion of each hip, 30 abductions of each hip, and 50 eccentric pronator contractions on each side. The program could be performed in one session or split into short sessions throughout the day. A physical therapist taught the exercises and checked that they were correctly performed. The participants also received a booklet to review the exercises. Follow-up visits Over the long term the women had to practice the exercise program daily and visit their physician 1, 6, and 18 months after the educational session. At each followup visit, correct exercise accomplishment was checked and exercise compliance assessed as described below. The times for the 1- and 6-month visits were calculated from the day of the educational session. At the 18-month evaluation, participants were requested to indicate the physical activities they initiated after the educational session and to complete again the Baecke and SF-36 questionnaires. Participants who missed the 18-month follow-up visit were telephoned and asked to complete mailed questionnaires. Assessment of exercise compliance The compliance rate was measured according to the method used in previous studies [13, 20]. For each exercise, weekly practice was calculated as the proportion between the self-reported mean number and the prescribed number of exercise repetitions in a week. To be compliant during the study, each participant had to (1) have practiced at least three of the four exercises, and, for each exercise, to have performed weekly at least 50% of the prescribed repetitions; and (2) have disrupted training less than 1 month before the 6-month follow-up visit and less than 3 months before the 18-month follow-up visit. 327 Statistical methods Qualitative variables were described with proportions and percentages. Proportions were compared with use of the v-square test. Quantitative variables were described with means and standard deviations (SD). The means of two independent groups were compared with use of Student’s t-test. All statistical tests were 2-tailed, with significance set at p<0.05. A logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the variables predicting exercise compliance. Following Hosmer and Lemeshow’s recommendations [21], the analysis was performed in two steps. First, explanatory variables were selected after taking into account both their clinical relevance and the level of significance in the univariate comparisons (p<0.05) of compliant and noncompliant subjects. Despite their lack of significance, some variables were included because of findings from previous studies [7, 22]. The studied predictor variables were (1) the method of recruitment (1 = informed by flyers and self-registered, 2 = instructed by physician to participate); (2) the level of education (1 = highly educated women who had studied in a university or equivalent, 2 = others); (3) current occupational status (1 = currently employed, 2 = retired, housewife, etc.); (4) family history of osteoporosis as suggested by participant’s beliefs (1 = yes, 2 = no); (5) personal history of postmenopausal low-impact fractures (1 = yes, 2 = no); (6) lumbar T-score £)2.5 (1 = yes, 2 = no); (7) femoral neck T-score £)2.5 (1 = yes, 2 = no); (8) contraindication for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (1 = yes, 2 = no); (9) score on the Baecke questionnaire assessing usual physical activity; (10) physical functioning; (11) vitality; and (12) mental health. The three last variables are domain scores from the SF-36 questionnaire. Second, the fit of several logistic regression models was compared after eliminating in a stepwise manner one or more possible predictors. The fit of each model was assessed by use of the concordant results of four tests of goodness of fit. The outliers in the solution obtained were checked by examinating residuals. Only the results of the best model are given here. The statistical software used was SAS version 8. Table 1 Characteristics of participants (n=135).HRT Hormonal replacement therapy Variables Mean ± SD Age, years Menopausal age, years Weight, kg Height, cm Fat, % Femoral neck T-score Lumbar T-score University or college educated Informed by flyers Family history of osteoporosis Low-trauma fractures Femur T-score £)2.5 Lumbar T-score £)2.5 Use of HRT Contraindication to HRT Use of bisphosphonate therapy Use of calcium supplements 59.6±6.2 48.98±5.3 59.14±10.44 159.5±5.94 36.47±7.15 –2.28±1.21 –2.35±1.23 Number 45 101 49 27 40 71 62 29 28 44 % 33 75 36 20 30 53 45.9 21.5 20.7 32.6 appendicular skeletal sites). The mean lumbar T-score was )2.35 (SD=1.23) and the mean femoral neck T-score )2.28 (SD=1.21). The lumbar T-score was £)2.5 in 53% (71/135) of patients and the femoral neck T-score £)2.5 in 30% (40/135). Among the 73 patients not using HRT, 40% (29/73) had a medical contraindication (15 breast tumor, 2 endometrial cancer, 3 endometriosis, 5 thrombosis, 1 meningioma, 2 lupus, 1 otospongiosis), and 15 were treated with bisphosphonates. Compliance results Compliance rates The 18-month exercise compliance rate was 17.8% (24/ 135) (39.3% [53/135] at 1-month and 28.1% [38/135] at 6-month follow-up), even though 84.4% (114/135) bought dumbbells requested for the exercise program. Reasons for withdrawal were lack of motivation (61%; 84/135), unrelated events (16%; 22/135), or pain related to the assigned training (4%; 6/135). No specific exercise was responsible for the lack of motivation (Table 2). Results For characteristics of the study patients see Table 1. Of the 142 women included at the baseline visit, 7 were not included in the final assessment because they had health problems (1 myasthenia gravis and 3 cancer) or personal events upsetting their lives (3 patients). The 135 participants averaged 59.6 years (SD=6.2 years). Most (75%; 101/135) were informed by flyers and self-registered, 36% (49/135) reported a family history of osteoporosis, and 20% (27/135) had a personal history of postmenopausal low-impact fractures (18 in the wrist, 8 in the ribs, 5 in the foot, 10 in other Table 2 Home-based exercise compliance in postmenopausal women (n=135) Exercise Compliant women 1 month Number Pronator Hip flexor Hip abductor Erector spinae Full program 59 61 61 41 53 6 months % 43.7 45.2 45.2 30.4 39.3 Number 37 40 45 30 38 18 months % 27.4 29.6 33.3 22.2 28.1 Number 24 29 40 22 24 % 17.8 21.5 29.6 16.3 17.8 328 Pain was the main reason for withdrawal of the erector exercise (7%; 10/135), and previous radial fracture or thumb arthritis often prohibited the pronator exercise (4%; 6/135). Predictors of 18-month compliance Univariate comparisons are shown in Table 3. The exercise compliance level was significantly higher in women with a contraindication for HRT (p<0.01). As well, usual physical activity as assessed by the Baecke questionnaire was associated with compliance (p<0.07). No significant difference was found in compliant women for the other explanatory variables. Logistic regression In the best model (Table 4), the predictors of 18-month exercise compliance were contraindication for HRT (odds ratio [OR] = 0.13; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.04 to 0.46) and general physical function score of the SF-36 questionnaire (OR=1.26; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.54). Moreover, a femoral T-score of £)2.5 tended to predict 18-month compliance (OR=0.34; 95% CI, 0.10 to 1.16). Changes in physical habits At the 18-month visit, 18.5% (25/135) of the study group, including 19 noncompliant women, were regularly practicing a physical activity initiated after the educational session (15 were taking gymnastics classes, including aquatic training; 3 jogging; 3 hiking; 2 biking; and 2 swimming). The 18-month level habitual leisure-time activity measured by the Baecke subscores was higher than baseline in nearly half of the participants. Thus, the level of sport activity increased in 35.6% (48/135) participants and the level of nonsport activity in 40% Table 4 Predictors of 18-month exercise compliance in 135 postmenopausal women. Results of logistic regression analysis Predictors Odds ratio 95% confidence interval Contraindication for HRT Physical functioning (SF-36 score) Femoral T-score £)2.5 Vitality (SF-36 score) Recruited by flyers University or colleg educated Currently employed Family history of osteoporosis Fracture(s) Level of physical activity (Baecke score) Mental health (SF-36 score) 0.13 0.04 0.46 1.26 1.03 1.54 0.34 0.83 1.80 1.61 0.10 0.66 0.47 0.83 1.16 1.05 6.94 3.13 1.80 0.64 0.58 0.18 5.56 2.19 1.11 1.04 0.27 0.99 4.57 1.09 1.07 0.88 1.30 (54/135). Comparison of compliant and noncompliant groups demonstrated a significant increment of the leisure-time sport activity (mean = 1.93 [SD=1.64] and mean = )1.06 [SD=4.04]; p=0.001, respectively) and nonsport activity (mean = 0.58 [SD=1.67] and mean = )0.89 [SD=3.53]; p=0.049, respectively). Impact on quality of life The global score of the SF-36 and its domains did not change at 18-month follow-up. Only two domains and one dimension changed differently in compliant and noncompliant groups: vitality (mean = 0.96 [SD=3.52] and mean = )0.38 [SD=3.33]; p=0.079, respectively), general health (mean = 0.83 [SD=2.55] and mean = )0.32 [SD=3.12]; p=0.092, respectively) and functional status (mean = 0.36 [SD=1.23] and mean = )0.03 [SD=0.95]; p=0.089, respectively). Table 3 Univariate comparison of postmenopausal women compliant and not compliant with an 18-month exercise program. HRT Hormonal replacement therapy Explanatory variables Recruited by flyers University or college educated Currently employed Family history of osteoporosis Fractures Lumbar T-score £)2.5 Femoral T-score £)2.5 Contraindication for HRT Age Level of physical activity (Baecke score) Physical functioning (SF-36 score) Vitality (SF-36 score) Mental health (SF-36 score) Compliant (n=24, 17.8%) Not compliant (n=111, 82.2%) Number % Number 19 9 12 8 4 16 10 11 79 39 50 33 17 67 42 46 Mean ± SD 82 37 71 41 23 55 30 18 59.71±5.73 84.84±8.25 26.04±3.00 12.79±4.68 18.54±4.27 % p Value Mean ± SD 73.9 33.0 63.7 36.9 20.7 49.6 27.0 16.2 59.32±6.46 79.33±14.06 26.65±4.16 13.59±3.51 19.04±4.61 0.59 0.57 0.21 0.74 0.66 0.13 0.15 0.01 0.78 0.07 0.12 0.34 0.62 329 Discussion Very little data are available on compliance with exercise therapy in routine medical care. The aim of the present study was to assess long-term self-reported compliance with a home-based exercise program described in a 1-day educational session added to usual medical care in France. One of the most commonly recommended lifestyle behaviors to prevent osteoporosis is adequate physical exercise. Numerous studies have shown that regular physical activity can increase bone density [12, 23] and that the bone-preserving action of exercise in postmenopausal women [24] may contribute to the prevention of osteoporotic fractures [3]. We selected the home-based exercise program on the basis of its site-specific effect of loading on bone remodeling [20, 25, 26]. Recommended contractions were submaximal, since strength training is supposed to be more osteogenic then endurance training [27]. It has been previously demonstrated that the hipflexion exercise in our exercise program has a lumbar bone–preserving effect, which is attainable in postmenopausal women [13, 20]. The impact of the home program on bone density was not assessed in this ‘‘real world’’ setting because it was assumed that concurrent pharmacological treatments for osteoporosis could mask the proper effect of the exercise training on bone remodeling. Despite an expected baseline motivation to change lifestyle behaviors in women mainly recruited via flyers, who had a personal history of fracture and/or low bone density as measured by DXA, long-term exercise compliance was poor, and the most common deterrent to exercise was lack of motivation, as was seen in other studies [28, 29]. Low levels of compliance to treatment recommendations are found across various health states; treatments [9], including HRT [30, 31, 32, 33, 34]; and ages. However, it was noticeable that, in the present study, at the 18-month visit, 18.5% (25/135) of the study group, including 19 noncompliant women, were regularly practicing an aerobic physical activity initiated after the educational session and that the level of leisuretime physical activity as assessed by the Baecke questionnaire increased in nearly 50% of participants. The home-based exercise compliance level was lower than that in published results from long-term prospective controlled trials in postmenopausal women (see [11, 12] for review). Thus, the use of hip-flexion exercise was higher in our previous study after 3-year follow-up (42%) [13] than in the present study after 18month follow-up (21.5%), although it was the same exercise and the same self-reported compliance assessment. In Hans and colleagues’ controlled study [14], 18-month compliance with an impact-loading program with use of a home Osteocare device was more than 80%, and in Smith and colleagues’ study, exercise compliance remained nearly 70% for as long as 48 months [10]. In controlled exercise trials, investiga- tors are probably more concerned than physicians about their routine, and patients are more engaged after giving informed consent. Indeed, the importance of attitudes in predicting intention to exercise and exercise behaviors has recently been highlighted [35]. Moreover, repeated incentives and evaluations that do not currently exist in usual medical practice might enhance participants’ motivation and compliance. Besides the methodological and psychological factors related to clinical controlled trials, the modalities of the training could influence compliance: a home-based training is less time-consuming, is inexpensive, and can be fit to any lifestyle. But such training is certainly less attractive than a program that includes running and dancing classes [10] and does not allow for the social interactions of group activities, which are thought to play an important role [34]. However, compliant subjects tended to feel increased vitality, improved functional status, and a positive health change. In the present study, the main reason for withdrawal was lack of motivation. A very brief program with a biofeedback mechanism such as that provided by the home Osteocare device [14] might enhance compliance. Therefore, there is a great need to identify factors that influence compliance with a home-based exercise program. In the present study, the strongest predictor of exercise compliance at 18 months was a contraindication for HRT. As suggested by den Tonkelaar and Oddens [36], women might be less concerned about osteoporosis once they are long-term HRT users. The opportunity for pharmacological treatment may put postmenopausal women’s minds at rest and decrease their motivation to improve lifestyle behaviors. Physical functioning, a domain of the SF-36 questionnaire that assesses limitations in performing all daily activities, also predicted 18-month compliance. Thus, a subjective perception of physical functioning and limitations was a predictor, even though the usual level of physical activity was not. However, physically active women are more likely to be compliant with long-term exercise [37]. Unfortunately, it has been shown that osteoporotic women with fractures have a low health status and a low level of spontaneous physical activity [38]. Few studies have assessed health-related measures of quality of life as predictors of successful completion of physical treatment [39] or as an outcome of physical activity programs [15, 40, 41, 42] in musculoskeletal disorders. Low bone density in the femoral neck, indicated by a T-score of £)2.5, tended to predict exercise compliance at 18 months (p=0.08). This score, which is the threshold of osteoporosis [43], could induce fear related to upper femur fracture and convince postmenopausal women to adopt appropriate lifestyle changes, even though other potentially upsetting risk factors such as family history of osteoporosis or previous low-impact fractures did not predict compliance. DXA has been proposed as a screening test for osteoporosis to help postmenopausal women use HRT, comply with HRT 330 [6, 33, 36, 44, 45, 46, 47], and comply with health-related lifestyle behaviors, including physical and dietary habits [7, 36, 44, 47]. But adverse DXA results can also induce lifestyle behaviors such as limiting physical activities to prevent falling [44]. Appropriate advice could forestall these changes. Regardless, in our study, exercise compliance at 18 months in postmenopausal women was low. Even more intensive interventions are ineffective in promoting 1-year adherence to exercise to prevent cardiovascular diseases [48]. Motivational strategies are needed to convince participants to train physically over the long term. Tailored advice and regular incentives from all health care professionals [42] could be a first low-cost step toward improving women’s awareness of the benefits of exercise besides pharmacological therapy after menopause. Unfortunately, most physicians, though aware of the health benefits of exercise, admit that they rarely address the subject with their patients [49]. Tailored exercise training and regular incentives could offset physical and psychological barriers to exercise. However, such considerations require convincing both health care professionals and patients to become engaged in exercise therapy. Conclusion An educational intervention, set in a unique session and added to usual medical practice, convinced only a minority of postmenopausal women to be compliant after 18 months with a home-based exercise program to prevent osteoporosis. Lack of a pharmacological alternative such as HRT contraindication or health factors such as subjective perception of physical function and limitations and, to a lesser extent, low bone density, predicted compliance. Identification of psychological profiles and physical health factors and tailored training could be considered to overcome barriers to exercise. References 1. Cummings SR, Melton J (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359:1761–1767 2. Leblanc AD, Schneider VS, Evans HJ, Engelbretson DA, Krebs JM (1990) Bone mineral loss and recovery after 17 weeks of bed rest. J Bone Miner Res 5:843–850 3. Kannus P (1999) Editorials: preventing osteoporosis, falls and fractures among elderly people. BMJ 318:205–206 4. Kohrt WM, Snead DB, Slatopolsky E, Birge SJ (1995) Additive effects of weight-bearing exercice and estrogen on bone mineral density in older women. J Bone Miner Res 10:1303–1311 5. Rothert ML, Holmes-Rovner M, Rovner D, Kroll J, Breer L, Talarczyk G, Schmitt N, Padonu G, Wills C (1997) An educational intervention as decision support for menopausal women. Res Nurs Health 20:377–387 6. Papaioannou A, Parkinson W, Adachi J, O’Connor A, Jolly EE, Tugwell P, Bedard M (1998) Women’s decisions about hormone replacement therapy after education and bone densitometry. CMAJ 159:1253–1257 7. Jamal SA, Ridout R, Chase C, Fielding L, Rubin LA, Hawker GA (1999) Bone mineral density testing and osteoporosis education improve lifestyle behaviors in premenopausal women: a prospective study. J Bone Miner Res 14:2143–2149 8. Rolnick SJ, Kopher R, Jackson J, Fischer LR, Compo R (2001) What is the impact of osteoporosis education and bone density testing for postmenopausal women in a managing care setting? Menopause 8:141–148 9. Dunbar-Jacob J, Mortimer-Stephens MK (2001) Treatment adherence in chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol 54[Suppl 1]:57– 60 10. Smith E, Gilligan C, McAdam M, Ensign C, Smith P (1989) Deterring bone loss by exercise intervention in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int 44:312–321 11. Oldridge NB (1992) Compliance bias as a factor in longitudinal exercise research: osteoporosis. Sports Med 13:78–85 12. Berard A, Bravo G, Gauthier P (1997) Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of physical activity for prevention of bone loss in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 7:331–337 13. Mayoux-Benhamou MA, Bagheri F, Roux C, Rabourdin JP, Auleley GR, Revel M (1997) Effect of psoas training on postmenopausal lumbar bone loss: a 3-year follow-up study. Calcif Tissue Int 60:348–353 14. Hans D, Genton L, Drezner MK, Schott AM, Pacifici R, Avioli L, Slosman DO, Meunier PJ (2002) Monitored impact loading of the hip: initial testing of a home-use device. Calcif Tissue Int 71:112–120 15. Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Winegard K, Ferko N, Parkinson W, Cook RJ, Webber C, McCartney N (2003) Efficacy of home-based exercise for improving quality of life among elderly women with symptomatic osteoporosis-related vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int 14:677–682 16. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–483 17. Baecke JAH, Burema J, Frijters JER (1982) A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr 36:932–942 18. Bigard AX, Duforez F, Portero P, Gezennec CY(1992) Détermination de l’activité physique par questionnaire: validation du questionnaire de Baecke. Sci Sport 7:215–221 19. Perneger TV, Leplege A, Etter JF, Rougemont A (1995) Validation of a French language version of the MOS 36-Item Short Health Survey (SF-36) in young healthy adults. J Clin Epidemiol 48:1051–1060 20. Revel M, Mayoux-Benhamou MA, Roux Ch, Bagheri F, Rabourdin JP (1993) One year psoas training can prevent lumbar bone loss in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Calcif tissue Int 53:307–311 21. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (eds) (1989) Applied logistic regression. Wiley, New York 22. Strentröm CH, Arge B, Sundbom A (1997) Home exercise and compliance in inflammatory rheumatic diseases—a prospective clinical trial. J Rheumatol 24:470–476 23. Gutin B, Kasper MJ (1992) Can vigorous exercise play a role in osteoporosis prevention? A review. Osteoporos Int 2:55–69 24. Heinonen A, Kannus P, Sievanen H, Oja P, Panasen M, Rinne M et al (1996) Randomised controlled trial of effect of highimpact exercise on selected risk factors for osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 348:1343–1347 25. Kerr D, Morton A, Dick I, Prince R (1996) Exercise effects on bone mass in postmenopausal women are site-specific and load dependent. J Bone Miner Res 2:218–225 26. Haapasalo H, Kannus P, Sievänen H, Heinonen A, Oja P, Vuori I (1994) Long term unilateral loading and bone mineral density and content in female squash players. Calcif Tissue Int 54:249–255 27. Rubin CT, Lanyon LE (1985) Regulation of bone mass by mechanical strain magnitude. Calcif Tissue Int 37:411–417 28. Johnson CA, Corrigan SA, Dubbert PM, Gramling SE (1990) Perceived barriers to exercise and weight control practice in community women. J Women Health 16:177–191 331 29. Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C et al (1995) Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medecine. JAMA 273:402–407 30. Cauley JA, Cummings SR, Black DM, Mascioli SR, Seeley DG (1990) Prevalence and determinants of estrogen replacement therapy in elderly women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 163:1438–1444 31. Coope J, March J (1992) Can we improve compliance with long-term HRT? Maturitas 15:151–158 32. Ryan PJ, Harrison R, Blake GM, Fogelman I (1992) Compliance with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after screening for post-menopausal osteoporosis. BJOG 99:325–328 33. Utian WH, Schiff I (1994) NAMS-Gallup survey on women’s knowledge, information sources, and attitudes to menopause and hormone replacement therapy. Menopause 1:39–48 34. Harrison JE, Chow R, Dornan J, Goodwin S, Strauss A and Mineral Group of the University of Toronto (1993) Evaluation of a program for rehabilitation of osteoporotic patients (PRO): 4-year follow-up. Osteoporos Int 3:13–17 35. Iversen MD, Eaton HM, Daltroy LH (2004) How rheumatologists and patients with rheumatoid arthritis discuss exercise and influence of discussions on exercise prescriptions. Arthritis Rheum 51:63–72 36. den Tonkelaar I, Oddens BJ (2000) Determinants of long-term hormone replacement therapy and reasons for early discontinuation. Obstet Gynecol 95:507–512 37. Rejeski WJ, Brawley LR, Ettinger W, Morgan T, Thompson C (1997) Compliance to exercise therapy in older participants with knee osteoarthritis: implications for treating disability. Med Sci Sports Exerc 29:977–985 38. Jalava T, Sarna S, Pylkkanen L, Mawer B, Kanis JA, Selby P et al (2003) Association between vertebral fracture and increased mortality in osteoporotic patients. J Bone Miner Res 18:1254–1260 39. Gatchel RJ, Mayer T, Dersh J, Robinson R, Polatin P (1999) The association of the SF-36 health status survey with 1-year 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. socioeconomic outcomes in a chronically disabled spinal disorder population. Spine 24:2162–2170 King AC, Pruitt LA, Phillips W, Oka R, Rodenburg A, Haskell WL (2000) Comparative effects of two physical activity programs on measured and perceived physical functioning and other health-related quality of life outcomes in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med 55:M74–M83 Salkeld G, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, Easter S, Seymour J, Kurrle SE, Quine S (2000) Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: a time trade off study. BMJ 320:341–345 Elley CR, Kerse N, Arroll B, Robinson E (2003) Effectiveness of counselling patients on physical activity in general practice: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 326:793–803 Kanis JA, Gluer CC (2000) An update on the diagnosis and assessment of osteoporosis with densitometry. Committee of Scientific Advisors, International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos Int 11:192–202 Rubin SM, Cumming SR (1992) Results of bone densitometry affect women’s decisions about taking measures to prevent fractures. Ann Intern Med 116:990–995 Torgeson DJ, Donaldson C, Russell IT, Reid DM (1995) Hormone replacement therapy: compliance and cost after screening for osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol 59:57–60 Newton KM, Lacroix AZ, Leveille SG, Rutter C, Keenan NL, Anderson LA (1997) Women’s beliefs and decisions about hormone replacement therapy. J Womens Health 6:459–465 Marci CD, Viechnicki MB, Greenspan SL (2000) Bone mineral densitometry substantially influences health-related behaviors of postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int 66:113–118 Harland J, White M, Drinkwater C, Chinn D, Farr L, Howel D (1999) The Newcastle exercise project: a randomised controlled trial of methods to promote physical activity in primary care. BMJ 319:828–832 Pinto BM, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH (1998) Activity counseling by primary care physicians. Prev Med 27:506–513