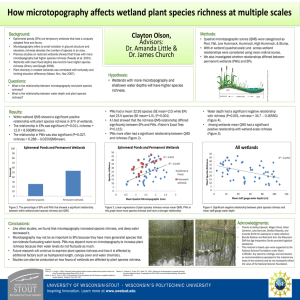

The effects of microtopography on ephemeral pond and permanent

advertisement

The effects of microtopography on ephemeral pond and permanent wetland plant species richness at multiple scales Clayton Olson, Amanda Little & James Church University of Wisconsin-Stout Ephemeral ponds (EPs) are temporary wetlands that host a uniquely adapted flora and fauna. Microtopography refers to small variation in ground structure and elevation; richness denotes the number of species in an area. Studies on restored wetlands suggest that those with more microtopography had higher species richness (Tweedy et al. 2001). Wetlands with lower flood depths also tend to have higher species richness (Cherry and Gough 2006). Plant diversity in created wetlands was correlated with tortuosity and limiting elevation difference (Moser et al. 2007). • • • • • • Wetlands with higher microtopographic scores (hummocks) and shallower water depths will have higher species richness. • What is the relationship between microtopography and plant species richness? • What is the relationship between water depth and plant species richness? • • pool • PWs had a mean of 32.93 species (SE =2.0) while EPs had 23.5 species (SE =1.0). (P=0.001, 2-sample t-test). A higher proportion of PWs had significant within-wetland relationships between QMS and richness. (Fisher’s Exact Test: P=0.115, Fig 2) Figure 2. The percentage of EPs and PWs that showed a significant relationship between within-wetland plant species richness and QMS. • • Within-wetland QMS showed a significant positive relationship with plant species richness in 37% of wetlands. At the wetland-scale, the relationship between mean QMS and species richness in EPs was significant and positive (P=0.003, richness = 5.81 + 11.0QMSmean, Fig 3). The relationship in PWs was also significant and positive (P=0.009, richness = 17.1+ 11.5QMSmean, Fig 3). Figure 3. Linear regressions of plant species richness versus mean QMS. PWs in this graph show higher species richness and have a stronger relationship. • • • • Water depth had a significant negative relationship with richness (P=0.001, richness = 34.7 – 0.165SG, Fig 4). Figure 4. Significant negative relationship between plant species richness and mean staff gauge water depth. Acknowledgments: Conclusions: • • Quadrat microtopographic scores (QMS) were categorized as Pool, Flat, Low Hummock, Hummock, High Hummock, & Stump. • With-in wetland (quadrat-scale) and across wetland relationships were considered using mean ordinal scores. • We also investigated whether relationships differed between permanent wetlands (PWs) and EPs. Hypothesis: Questions: Results: Methods: http://sofia.usgs.gov/geer/2003/posters/microtopo_char/ Background: Like other studies, we found that microtopography increased species richness, and deep water decreased it. Microtopography may not be as important within EPs because they have more generalist species that can tolerate fluctuating water levels. PWs may depend more on microtopography to increase plant richness because their water levels do not fluctuate as much. Future research will continue to examine plant species richness and how it is effected by additional factors such as hydroperiod length, canopy cover and water chemistry. We are also conducting studies on how fauna of wetlands are affected by plant species richness. Sources: Cherry, J. A., Gough L. (2006). Temporary floating island formation maintains wetland plant species richness: the Tweedy, K.l., Scherrer, E., Evans, R.O., Shear, T.H., (2001). Influence of microtopography on restored hydrology role of the seed bank. Aquatic Botany, 85(1) 29–36. and other wetland functions. Proceedings from 2001 ASAE Annual International Meeting. Sacramento, Moser, K., Ahn, C., Noe, G. (2007). Characterization of microtopography and its influence on vegetation patterns in California, USA. created wetlands. Wetlands, 27(4) 1081-1097. • • • Thanks to Ashley Kijowski, Megen Hines, Adam Cameron, Leta Ganrude, Shelby Kilibarda, and Amanda Smith for assistance in data collection. Brenda Rederer and Rod Gont from the Wisconsin DNR-Ice Age Interpretive Center provided logistical assistance. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant 1256142. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.