TOP SECRET PART ONE—FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS I. THE JOINT INQUIRY

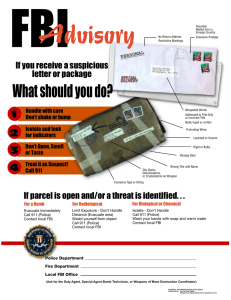

advertisement