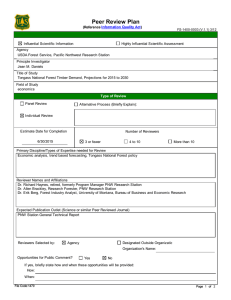

Bird, Mammal, and Vegetation Community Surveys of Research Natural Areas in the

advertisement