This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text... by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may...

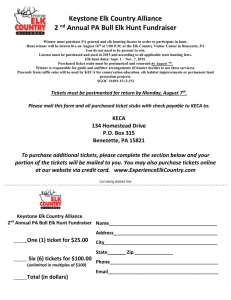

advertisement