Western Juniper in Eastern Oregon

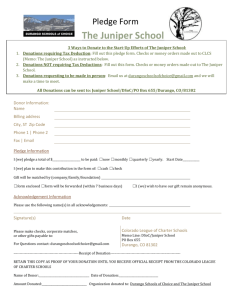

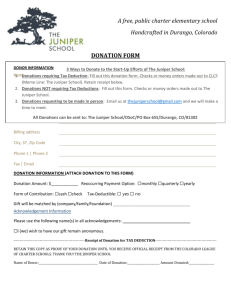

advertisement