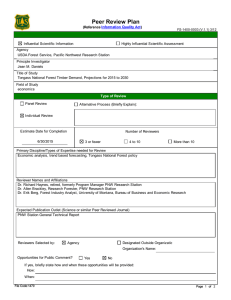

Social Implications of Alternatives to Clearcutting on the Tongass National Forest

advertisement