by

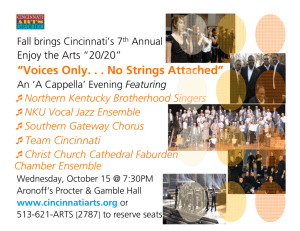

advertisement

Adaeio for StriDes;

Analysis for Interpretation and Rehearsal Preparation

An Honors Project (Honors 499)

by

Matthew Tipton

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

of the Honors College curriculum.

Project Supervisor

Dr. James Austin

Ball State University

Muncie, Indiana

1 May 1992

Date of Graduation:

2 May 1992

"..

"

r-;·-7

',',..

I

...., i,/'

.....

,

,

/~,;:;r

orieins

When attempting to interpret any composition, it is very helpful to understand the

circumstances surrounding its origin. A good interpretation is sensitive to the overall intent of the

work as well as the individual moments of tension and release that help to convey the mood.

Therefore, any information about the composer or his motivation for writing the piece will be of

assistance.

Adagio for Strings by Samuel Barber (1910 - 1981) was originally

c\

the second movement J Quartet in B minor, op. 11. It was written in the late

summer/early fall of 1936 and the Pro Arts String Quartet premiered the

work in December of the same year. Early in 1937, however, Barber

adapted the slow part of the second movement, "Molto adagio," for string

orchestra. The" Adagio" has ever since overshadowed its parent

composition and has become, perhaps, Barber's best known work. It too is

marked "Molto adagio" and remains opus 11.

The string quartet, while a lovely setting for the "Adagio," limited its

potential. Once set for a full string ensemble, the "Adagio" was able to take

on a life of its own. and should not necessarily reflect its

origin~

The

"Adagio" is an adaption, not merely a transcription. Often, when a work

originally written for one instrument or ensemble is being played by

another instrument or ensemble, the conductor/performer may choose to

use techniques that mimic the composer's original medium. For instance, a

Bach prelude and fugue transcribed for winds may use dynamics and

phrasing similar to an organ. This process of interpretation does not apply,

however, to the "Adagio."

3

Phrasing is a good example. The slow tempo that characterizes most

interpretations of the" Adagio" simply would not be possible with a

quartet because bow changes in the middle of the notes would be obvious.

Similarly,ryhe potential of a small ensemble to create dynamic contrast

differs from that of a large ensemble. While a quartet is capable of much

softer dynamics, a large ensemble playing with great sensitivity can

achieve a very effective pianissimo that should not be underestimated. The

large ensemble, of course, lends itself to the strong dynamics - especially

those used in the climax of the piece.

Cbrono)o&ical Analysis

This analysis will address several aspects of the composition that mayefi~

,------- rehearsal

techniques as well as interpretation. Specific points of discussion will include:

Player problems. These are places that are especially demanding of the players. By

recognizing these problems in advance, it may be possible to minimize the difficulty.

Conductor problems. Similar to the player problems, these are areas that should be

identified and practiced prior to rehearsing the ensemble. Unresolved conductor problems often

become player problems.

Tension and release. Several factors, including but not limited to harmonic structure,

tempo, rhythm and range, contribute to sections of tension and release. These sections should be

recognized in advance so that they may be capitalized upon. The overall effect of the piece is a

compilation of these areas. The factors creating the tension or release will be identified in the

analysis.

Major musical moments. These are specific points that especially important to the

advancement of the mood of the piece. The factors that create a particular major musical moment

will be identified in the analysis.

-_/'

4

The first player problem that should be addressed is the key

signature. The key signature of five flats is used throughout. Younger or

less experienced players should have prior instruction that properly

prepares them for this key. Scales and exercises in D-flat major as well as

B-flat minor are advised. "Adagio" is in the key of B-flat minor, though at

no point is the tonality firmly established. Because this inherently means

there are a lot of accidentals, this piece would not be a good introductory

piece to the five ...flat key signature.

The 4/2 time signature is a conductor problem that should be

discussed with the ensemble as well. Where to, or not to subdivide should

be considered carefully. At times it seems natural to subdivide, at other

times impossible. Individual places for consideration will be pointed out. It

should also be noted that when a slower tempo is chosen, it is more taxing

on the less experienced musician as it places more responsibility on the

player to subdivide internally and bow carefully.

This piece requires clear communication between conductor and

performer. It is usually the player who is reprimanded for failing to

maintain eye-contact. If the player looks up often but rarely finds the

conductor looking back, very little communication will occur - even if the

conducting gestures are very clear. The constant entrances and exits of

sections that occur during phrases make this aspect of good communication

imperative. Memorization of the score is advisable when ever possible.

5

The unaccompanied first violins enter on the key center, B-flat. On

beat three, the rest of the sections enter as cued by the conductor. This

entrance turns the key center into the fifth of a minor seventh chord built

on the fourth scale degree. There is a brief tension - release pattern as the

ensemble enters and resolves the initial chord to a major five chord that is

sustained. The violins' B -flat now becomes a four-three suspension and

serves to sustain tension as well since this begins the churning plea that

Barber uses throughout the piece.

When the ensemble first speaks on the third beat, it is an intense,

reassuring response to the violins that creates a texture change. Though

stylistically very different, this bares some resemblance to the call and

response of the Negro spiritual. This pleading reinforcement constitutes a

major musical moment.

The violin line continues in an ascending sequence filled with nonharmonic tones. This serves to gradually heighten the tension and keeps

the original resolution of the ensemble from being mistaken as resignation.

Finally, the chord changes to a major seventh chord built on the sixth

degree and resolves inward to a major seven chord giving a sighing effect

to the plea.

In the fourth measure, a single 5/2 measure, the first violins begin a

similar solo statement - this time on the fourth beat. The ensemble then

replies on the fifth beat and there is another major musical moment. The

6

firsts begin the theme on a C this time, however, and that subsequently

becomes the dominant seventh of a major three seven chord in the first

inversion. This resolves inward to a major six chord - a secondary

dominant/tonic relationship.

The theme resumes, although the sequence this time is descending.

This does not, however, serve to release the tension, partly because the

ensemble changes to a minor four seven chord that also moves downward.

As the phrase comes to a close, tension is released at least to a point of

equilibrium as the chord resolves inward to a major five chord.

Measure eight is very similar to the beginning. The emotional tension

and release patterns are the same, but perhaps at a relatively lower

degree. The ensemble entrance is no longer a major musical moment as it

is now expected by the listener.

In measure eleven there is a slight change from the original and in

measure twelve there is a complete departure from the original that, with

the help of a crescendo, becomes a major musical moment on the last beat

of the measure as the first violins climax on a high C-flat. The first change

occurs as the first violins jump a trijtone to the minor seventh making a

dominant seventh built on the seventh degree in measure eleven. The

tension then builds more as the chord first becomes a/minor five seved in

the first inversion and then changes to half-diminished. The careening

theme is now picked up by the violas.

7

The second violins drop out at measure twelve and need to be cued

back in on the third beat of the fourteenth measure. Measure fifteen is a

6/2 measure and if is to be subdivided, works best as four groups of three

quarter-notes. The seconds and violas must, however, be very careful of

their cut-off and re-entry as this method of subdivision caters to the firsts

with the theme.

In measure sixteen, the violas recover the theme and carry it to

measure nineteen. There is a tremendous release of tension as the

ensemble lands on a solid tonic chord. This starts a measure-long major

musical moment as the violas, on the third beat, lead of the pleading theme

for the first time. E-flat is the starting point of the theme this time,

however, the following chord structure is the same as the beginning. The

other sections respond accordingly - except the basses who are, for the

moment, tacet.

The violas continue, increasing the tension, for three measures. In

measure twenty-two, the firsts take over and end the phrase in measure

twenty-three. It may be advisable to subdivide the fourth beat of measure

twenty-three so as to cue the sustaining firsts as they resume the theme.

/,;--,

Measure twenty-six is similar to measure fiftee~may be

subdivided similarly. This caters to the violas now, however, and the. first

may have a player problem similar to the violas previously.

]n

any event,

the firsts should receive a cue on the and of the fourth beat. From here, the

8

tension gradually relaxes with the descending lines until release at

measure twenty-eight on B-flat major.

The cellos, the lowest voice in the absence of the basses, begin the

theme on B-flat. The chords and theme, though completely re-voiced, are

exactly as they were in the beginning. The cellos, starting in measure

twenty-eight are playing in tenor clef and starting in measure thirty-nine,

treble clef. This may be a player problem for inexperienced players.

However, this piece would be an excellent introduction to clefs as it uses

mostly diatonic motion.

In measure thirty-one, a 5/2 measure, the phrase ends on beat two

for the violas, beat three for the cellos and beat four for the seconds. The

cellos resume on beat four and the violas and seconds on beat five. This

creates a minor conductor problem. Subdivision is not recommended. The

less movement the better here as there is actually very little movement in

the music. It is more important, in this instance, to be aware of motions

that may suppress the players than to find a way to cut-off or cue. It is

advisable to cue in the firsts, however, in measure thirty-two.

The re-voiced repeat of the beginning continues throughout this

section and the tension release pattern is also repeated. This time, over

measure thirty-six, Barber actually wrote out ({with increasing intensity."

This foreshadows the impending climax and departure from the original.

The tension should not necessarily be higher than the beginning at this

9

point. Barber's marking is simply a warning that this time the tension is

going to get higher and it is going to take longer to get there.

Further departure from the original occurs in measures forty-two

and forty-three where there is a 3/2 measure following a 4/2 rather than

a single 6/2 measure. The 3/2 measure should not be sub-divided.

In measure forty-four the violas start playing in treble clef. This will

be a player problem for most. The seconds also are asked to remain on the

G string at this point, forcing them into very high positions to accommodate

notes more than an octave above the G string's fundamental.

By measure forty-eight all sections (except the tacet basses) are

playing in a foreign clef and/or an extremely high register. In measure

fifty, the piece climaxes for three-and-a-half measures ... through

homophonic chord changes, in an extremely high register and at a

fortissimo dynamic. In measure fifty-three, the unison cut-off followed by

extended silence (held half-rest) creates a major musical moment.

When the ensemble finally re-enters, it projects an entirely different

mood. The basses now return and all sections are in their natural clef. The

dynamic is pianissimo and the register is comfortable for all. It is a

whispered restatement of the previously wailed plea creating another

major musical moment. This is the only point at which the piece conveys

relaxation. In fact, at this point there is resignation.

Measure fifty-seven begins with silence following a cadence on the

10

dominant in measure fifty-six. This leaves expectation in the air as the

sound resumes. It is the firsts and violas in octaves that break the silence

with the familiar plea on the familiar B -flat with the familiar chord

structure - but this time muted. The plea now comes to us in a dying

breath but with equal intensity in its question as it cadences on the

dominant in measure sixty-four.

The tension begins to mount briefly when the firsts and violas seem

to give an abbreviated plea which quickly finds the dominant question

mark in measure sixty-six as if for the last time. An echo from the firsts

comes, however, an octave lower. The half-notes marked "molto espr." in

the firsts in measure sixty-seven should be cued individually as the rest of

the ensemble sustains the last breath marked "morendo." The ensemble is

cut-off leaving the firsts' plea sustaining into the last measure. Then the

last sighing exhale comes from the ensemble on the same chord - the

dominant. The plea is not answered.

Overview and Conclusions

At the time the String Quartet in B minor was written, Barber was

studying at the American Academy of Music in Italy. This is also where the

Pro Arts String Quartet premiered the work and originally it was most

likely submitted for a grade. This is the only example of a string quartet

by Barber as he generally limited himself to one composition per genre.

11

This was not true of the lieder. Barber had an amazing talent for setting

words to music. Ralph Vaughn Williams once expressed his admiration for

Barber's "Dover Beach," a baritone lieder set to the Matthew Arnold poem

of the same title. Apparently Vaughn Williams had tried on numerous

occasions to set the poem to music and was unsuccessful. Barber later

reflected that this compliment was quite a boost in his early years.

Perhaps the best compliment Barber could receive was the

circumstance surrounding the first performance of "Adagio." Arturo

Toscanini selected it for premier by his NBC Orchestra soon after it was

adapted for strings. This was unusual for Toscanini as he did not favor

American music and was not partial to new works. He featured the piece

on a South American tour as well.

The "Adagio" became fairly well known and in 1945 was played

immediately following the announcement of the death of President

Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was also played in remembrance of Princes Grace

of Monaco and was used in movies such as The Elephant Man and Platoon.

Eventually "Adagio" became synonymous with requiem. One obituary for

Samuel Barber even read "Adagio for Sam."

The piece is, in fact, a lament; a plea out of total frustration, if not

hopelessness, for final peace and rest. In 1967 "Adagio" finally got a voice

as Barber set the music to text and transcribed it for unaccompanied SATB

VOIces.

12

Agnus Dei, qui tollis

peccata mundi:

miserere nobis.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis

peccata mundi:

dona nobis pacem.

Translation:

Lamb of God, who takes

away the sins of the world:

have mercy upon us.

Lamb of God, who takest

away the sins of the world:

grant us peace.

The new piece was named "Agnus Dei" accordingly. Although the

piece had already been interpreted as a requiem, this text does not seem

to interfere with that interpretation. The final two measures seem to be a

final plea for peace just before death. The unresolved dominant seems to

leave the listener hanging - wondering if the plea was answered. The

listener is forced to answer the question for himself and thus, Barber has

created a piece of music that never really ends. It burning plea smolders in

the mind of the listener. .. searching for resolution.

Appendix

tension and release

1¥R4't=f=t+ til 11

1

2

~

4

S

f

1

8

.9

10

11

12

n

~ Fill ==t'y 1===r 1 1l'=1

14

15

15

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

25

t==T'l11111 r-tlill

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

35

37

38

39

1 1 l i t 1 1 11 1 1+1 ~

40

41

42

43

44

45

45

47

48

49

50

51

52

~l ~ I ti4l'+t1=H 1

53

54

55

55

P+ti= II

M

57

58

59

57

58

59

50

51

52

53

54

55

1 .'

i

(

To my aunt and unc/tI, Louistl and Sidney Humer

IplaYi~ time,

min.

7-S

I . -.

, -

Adagio for Strings·

~

0.J':")

Samuel Barber, 0,

Malta adagio

?r,JJJnt~

1

I

"

Violin I

l

Violin 11

-'A ,-- -=-

l

pp ~

t)

",

...

"

'~"

-- -...

f. q18f__

-

+

)"

,

f=

,"'

p

lP

I

---

--~

P

11'

---

-~

P

p=

1'-'1-

~

.....

-

.....

--.R , J:::-ft-J

.-

A'

-

...

..on)

pp

I

---

A I

...

~~

=:

I

I

---

~-

7::if-

/_0 .

,

I

--

---::::--

"!t~_ _

--'1

:>

Vln.I

t)

r=

3

P

¥~

Double- Bass

P

IUI _ _ _ M ___

I'"

.

~

l

~

.

. pP-==

~

-orr

P

_.

U·

Viola

Violoncello

--

....

I

:

...

T -z....

I

I

Pf

l

j)

___4 u·

~

---1

...

=i

}J

...

p--==

=

"

)

...,.

~1et

1

D.-B.

'U

181*From "String guarret in B

.'

.'

,

38577 C

mino~ i'

...

...

...

""-

pp

~'"

~

,

1'-'1----

--,.

.

-'"

-

Cop' righ~, 1939, by G. 8cA.irmer, Inc.

International Copyright &cured

;:n;d~eU'S'A'

=

~

I

_<J

1"1.

=-

,,-'pr.~

VIa.

V,

1

~!

to

{,

----

~1

I

1:

til

I •.

I

i

I

I

t

---

'I~

~~

J" /

Vln.l

-U

111

"

p

--

-- ,,,

:j -

:--+

"""il

P

---

Via.

D.-B.

J

l!

.J

~

"I~

-rr::-}. l

--,

,77

""

Ii

, ..

"U".

-

...

'\

i.

='Isf-.'~

--...

...-- -: I, _

- ,_

___

-

.....

t

..

I

I

I

11ft

:

l

_.

---

,~

.

I

Vln.II

Vc.

,

I

.

n

/

,.'

/~ \\.'

II

'OJ

t

"U,

/.

• -,J!1 ~

.

-&-

.'

'.

,

I~

T°"~,K

\

:.::::;;: " :>

---.

Vln.I

--;-

tJ

~

~iv.

"

"

I

Vln.n

tJ

~~

4-~

p

,

--

VIa..

--..

~

.

I

;I

'

q______ I

'-- --'

.-

P' /orte, sempre cantando

unis.

Ve.

4-

-tel-

"U

.....

'p

.'

D.-B.

'\

jEll-

"U

. -=-----

Via.

-=

,'\.

\

Vc.

-

I~

l

'\

38577

-

..

111-==

.~,

~

'.

-

p

.-

'Iff-=='

all

-=

p

t-..

::'fp

J3

~4

r- " _ . _ - - --- - --

I

.

j"

Vln. I

.) ~

l

..,

-..:::

"

Vln. II

-p

.

unis.

p-

~~,

-------:J,

WI

-.

Via.

l

~

-

=

-----~

~.

,

-

" ....

J "

I

t

v,.nl

I(T-) '.\

' "

.....-:

.J-.--"

crtJsc.

~'l

(

~

__...._____ 4 '

Y

--

""-

--- ' ...-- ""-

1--""

--~

.,~ ~'

Illn , L,"=-~'

mf

3/

30

1"1--""-~-

,

---

'""

-

--

!:e.

:

-- -

-------

-

1 '

==--

-;;;;tA rJtTre-asiiij'intensity

-

,.

---

""

-

-

"'-P

~espr. canttt14d~

.......

WI

;::;..---

-----

p

WI

..A_I

-

1

-===1

,

-- -

-

,

unis.

Ve.

'ii'".

--

,I

j'

-:

I--

--- ,

::r--

--

----

>

I:

!, :

,

I,

Ve,

'\

r II

~

P

[!]

,

P

t:re8C.

~

Vln. I

II

lItfespr.

Vln.II

--

f

non div.

= lItf

--=

.........

unia .

VIa.

!

I

~

I

I

i

.',

~

'1,

I <,:

A •

j

J

r

t

t

~=

--;~~~~~~~ ~E~~~~~~ E

--

(

"

I

"I

Yin. II

~.Q.

~ ~,

=

- -

~

Yla.

I";:-.p..

.(J..

"

~

-

~: . -

-

- - -

--

A.

~:

--

:!!::

--

-e:-:e.

-

-

:!!:

-

tl.

=~-

f

38577

~

,

.

,

pp

~~ t-'-e: i 1":\ 1

i

Ii

jef-

no

L

-= Ill' ......-, h....

L

-

t-f':

--

·rtf

--

pp

,PP

r.. 1

pp

1":\;

r... I

1":\

r...:

,

,

i

'f'~

I

I

i

.~

.'

::pp

.+

·ff

_........

;'7.7

.~1r.

'wJ

If

..

.Q.

r

1":\)

'JJ

~ r--.Q.

i

,

-~t:\

-

R---=>5

pp

-

"

I:\~

~.o."-.Q.:

..,.~

.

,

-11":\

'JJ

. . -.Q.

.Q.

= j ."

tJ

D,-B

1":\

I":\t

:.:? ~.Q.,

JJ

-&-" r--_

=

- - --=

tJ

Ve.

--

""

f-:

=

:!!::

oJ,

e:

~

-6

II

~

~

~~~~~f:~~~ I,..~~~~~~g

11=~~~~

tJ

1

.0.---"".Q.

--

'w"

tJ

Vln. I

~

t

:!!::

iPP

I

i

,,"0. F

I":\~I":\;

pp

sf

L

..

I•

I

'%

1 Ie.1 ''1"'J

'-.:;:;-

Tempo 1° (sord ad lib)

anis.

1

1\

Vln, I

.,

ei

--=

1llfespr.

,. 1

ei

~

....

;e!-

- -

V-

p--

AI

q_-II""

ei

~u ~-e-

div.

Via.

-fI'

Ve.

ij .... "'0

-

l

q-e- ....

'\

-

)lLl

Vln, I

---

I

v..,~

.....

-e--

!

T

Ve.

]

D.-B.

l

,

..

--==

,, .

....

M ___

-

_v

~ ,

,

U_"?1~~~-

r

-

w.,

__

_-e-

~

paup

!

'1:'

Q~

. pp

, I

pp

morendo

pp

morendo

,

.....

....

r

~pzup

-

_....

n

M

morendo

pp

1'-'1_

1II0rendO

-,...,

-,...,

piup

pp ""-

1tlorendo

I:'

.j

morendo

I

piup

r.-

, F t:"-

- -

pp

l'

'I

1-

Ntf=piup

.Y ~,

(0

J

,

I

P

CJ

'l -,'Gwr:~

It es

"'-"'0

I

I

I~

_"'"

JUI.

p

--.,..,1S,

18I-~~_i'Bt'

----

-

I'

-----

==

,t

, ,.

P

It '-

--

,.....,

:

.,

Via.

",

i

(,)

~--

,

1

IIlfespr.

iLl

..,

,

----

u-

P

==

ei

_<§I..

un~

....

I"

~'U-

-

<- - ,-

~

-""

{I':"-

....,

,

I':"-

'--

~IU

~

, : 1':'1

....,

38577

..

I