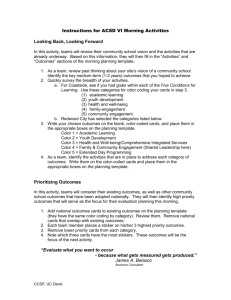

Results and Indicators for Children:

advertisement