2012 Report Health Colorado’s Forests

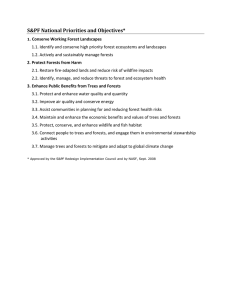

advertisement