a GAO Department of Justice Major Management

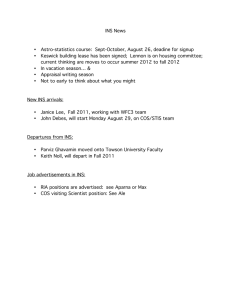

advertisement