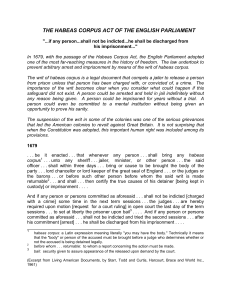

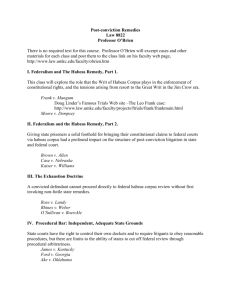

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Petitioners,

advertisement