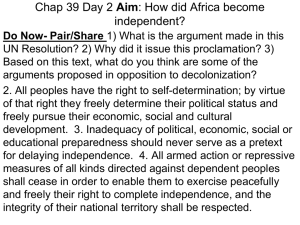

( ALGERIA’S STRUGGLE AGAINST TERRORISM HEARING COMMITTEE ON

advertisement