United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations

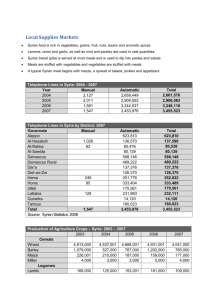

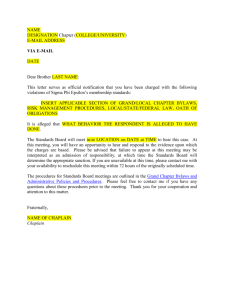

advertisement