The Future of Native American Imagery in Sports

advertisement

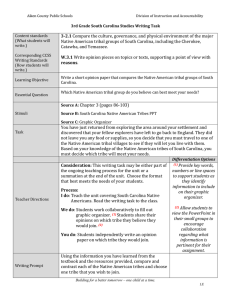

The Future of Native American Imagery in Sports Colleges are partnering with tribal groups to figure out how symbols should be used. A student performs as the Seminole warrior Osceola at a Florida State game. Mike Blake / Reuters Autumn A. Arnett Nov 21, 2015 Education When California recently became the first state to officially outlaw use of the term “Redskin” for mascots throughout the state, it again sparked conversation over the use of Native imagery and likenesses in sports—from amateur to collegiate to professional. Gyasi Ross, an author and speaker who hails from the Blackfeet Nation and Suquamish Nation, says, “When you’re talking about mascots or prohibited words … it is always about power and/or access.” “It’s the portrait of privilege when [the Washington football owner] Dan Snyder says, ‘This is how you’re supposed to feel about’” his team’s persistent use of the word,” Ross continued. “Because our ancestors suffered for that history and had faithfulness to survive that history. … Far be it for any person not of that family, not of that tribe, not of that community to have an opinion on this.” “The origin of the word comes from the historical context. It was published in newspapers in the West—placing bounties on Native [people], using the R-word. So how can it be thought of as being anything but derogatory and a hate word?” asks Robert Holden, the deputy director of the National Congress of American Indians. Holden’s NCAI colleague, the legislative associate Brian Howard, agrees. He pointed out that many of the Native representations in collegiate and professional sports sprung up “in the early 1900s, when a lot of the perception by the general populace toward Native Americans was that we were a dying race, in terms of actual numbers and as concerted efforts to try to assimilate Native peoples into mainstream society and to do away with” the idea of sovereign nations and cultures. Howard notes that the argument that the names are intended to honor, not offend, are flawed. Ross challenges where the line of acceptability is drawn by the non-Native majority in this country. “If ‘Redskins’ is an inappropriate title, then we shouldn’t use any Native names,” he suggests. Holden agrees, saying, “I would like to do away with all of them. They’re all derogatory, they use caricatures, and they all use the things that Native people use as part of our culture … Eagle feathers within Native communities and societies [are] given for doing good things for the community, for their families … and for warriors who faced death defending our homelands, so these are things that are not taken lightly.” Holden and Howard point out that to associate symbols that mean so much to the tribal community with something as trivial as athletics is insulting and derogatory. “To kind of minimalize that into a sports setting doesn’t really do them honor,” Howard says. Holden says that it is important that other states follow suit and that Native representation across all levels of sports stop. He is encouraged, though, that there appears to be growing support for this perspective. “There are a lot of folks out there who are like-minded and rational thinking and they’ve become enlightened,” he says. “Sports writers, President Obama, [and] members of Congress” have expressed support, and “schools across the country are changing [their] mascot, caricatures, and names.” Such actions are a move in the right direction, says Holden. “How is it that folks can’t understand or see what is the truth? … Why they’re being so obstinate or not willing to be educated about Native people and what this really means and what it stands for” is puzzling, he continues. Ross says it isn’t necessarily for people to understand. “This isn’t about subjective offense,” he says. “It’s about voice. … It’s about saying we have enough agency, autonomy, and intelligence to decide what’s right for us.” In Tallahassee, Florida, one institution, aided by a regional tribe, has worked hard to show that not all representation of Native imagery and symbols are created equal and at least one tribe is being given the opportunity to decide exactly what works for it. “For almost 70 years, Florida State has worked closely, side by side, with the Seminole Tribe of Florida in a relationship that is mutually supportive and built on respect,” says Browning Brooks, the assistant vice president for university communications at Florida State University. The university, whose athletic teams are known as the Seminoles, embraces its relationship with the Seminole Tribe of Florida and considers members of the tribe community partners. The tribe’s involvement is critical to the success of the university, say officials, not just a group of people whose name might conjure up inspiring imagery for student athletes on a war path. “This may be splitting hairs,” Brooks says, “but we do not have a mascot.” The student who portrays the great Seminole warrior Osceola and rides the Appaloosa horse Renegade during football games must maintain good grades and demonstrate personal character. Portraying Osceola on game days is a great honor and one that is supported by members of the tribe, the women of which sew the garments worn by the Osceola actor, according to the university. At Florida State, Brooks says, the university maintains an ongoing relationship with the tribe that goes beyond just “a man in feathers on a horse” riding out on game days. Instead, the university has “the honor” of being affiliated with the tribe, which administrators work hard to integrate into the entire university experience. Tribal liaisons are heavily consulted on many university initiatives; they are also included in the shaping of many traditions and are invited to celebrate in many of the most prestigious ceremonies on campus. In exchange, the university helps to preserve and teach the culture of the only Native American tribe never “conquered” by the U.S. government, as they never signed a peace treaty. Tribal members also crown the homecoming chief and princess with authentic Seminole regalia. “The university welcomes these opportunities to expose our students, faculty, staff and alumni to the Seminoles’ history and traditions and reflects what we value as an institution: multiculturalism and diversity,” says Brooks. The relationship, she says, has been endorsed on both sides. “In 2005, the Seminole Tribal Council took a historic step and passed a resolution affirming its enthusiastic support for the university’s use of the Seminole name, logos and images,” Brooks continues. The resolution “recognized Florida State’s continued collaboration with the tribe to include prominent participation by tribal members in many of the university’s most meaningful events and to seek advice and direction to make sure the tribal imagery we use and the history we teach our students are accurate and authentic,” Brooks says. Not lost on the Florida State community was the fact that the resolution passing was unusual for a culture that “rarely puts such things into writing,” according to the university. Due to the uncommon nature of the resolution cementing the institution-tribe relationship, members of the university community say they feel the gravity of responsibility accompanying the representation. “If at any time [the tribe’s members] were to decide they are not okay with” the use of the Seminole name, logos, imagery and likeness, says Brooks, “it would stop immediately.”