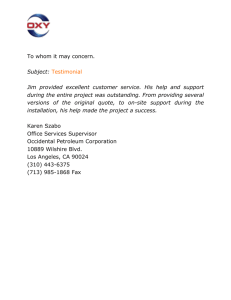

Testimonials versus Informational Persuasive Messages: The... Delivery Mode and Personal Involvement

advertisement