Document 10752550

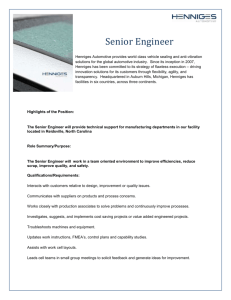

advertisement