Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Acta Psychologica

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/actpsy

Non-linear gaining in precision aiming: Making Fitts’ task a bit easier

Laure Fernandez *, Reinoud J. Bootsma

UMR 6233, Institut des Sciences du Mouvement E.J. Marey, 163, avenue de Luminy, CNRS and University of the Mediterranean, 13288 Marseille Cedex 9, France

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 17 December 2007

Received in revised form 29 May 2008

Accepted 2 June 2008

Available online 15 July 2008

PsycINFO classification:

2330

Keywords:

Perception–action coupling

Precision aiming

Movement kinematics

Behavioural dynamics

a b s t r a c t

The role of information in the processes underlying kinematic trajectory-formation was examined by

manipulating the relation between effector space (movement of a hand-held stylus on a graphics tablet)

and task space (movement of a cursor on a screen where targets were presented) in a precision aiming

task with five different levels of task difficulty. Movement patterns were found to evolve as a function

of the flow of information in task space, with participants (N = 13) producing more rapid and more fluent

movements when the mapping between spaces included the softening-spring characteristics typical of

behavioural patterns at higher levels of task difficulty. We conclude that the kinematic changes (movement time and pattern) observed when task difficulty increases result from informational influences.

Information affects behavioural dynamics at the level of the parameters without affecting the underlying

dynamical structure.

Ó 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The kinematics of movement provide a window into the processes underlying perceptuo-motor control. According to the theoretical framework adopted, characteristics of the movement have

been taken to express the characteristics of central motor commands (e.g. Keele, 1968; Schmidt, 1975), the interactions between

motor commands and properties (visco-elastic and other) of the

neuromuscular system (e.g. Feldman, 1966; Feldman, 1986; Hogan, 1984) or the organizational dynamics underlying movement

(Beek, Schmidt, Morris, Sim, & Turvey, 1995; Kay, Kelso, Saltzman,

& Schöner, 1987; Kelso, 1992). In search for appropriate experimental paradigms capturing the richness of goal-directed behaviour in the simplest possible settings, aiming movements have

been extensively explored, starting with the seminal work of

Woodworth (1899). Although analyses of point-to-point movements have revealed a variety of important empirical observations

(e.g. Atkeson & Hollerbach, 1985; Goodale, Pelisson, & Prablanc,

1986), the aiming paradigm proposed by Fitts (1954) perhaps captures the problem of goal-directedness in the most elegant way.

With distance D corresponding to the gap between the current

and the desired situation and target width W specifying goal tolerance—implying only two independent variables, measured along a

single dimension—it allows experimental control of task difficulty.

The latter is operationalized through the Index of Difficulty (ID),

with ID = log2(2D/W) being the most commonly used variant.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +33 491172275; fax: +33 491172252.

E-mail address: laure.fernandez@univmed.fr (L. Fernandez).

0001-6918/$ - see front matter Ó 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2008.06.001

When task difficulty increases, the time required to successfully

complete an aiming action also increases. This robust empirical

relation has come to be known as Fitts’ Law (see Meyer, Abrams,

Kornblum, Wright, & Smith, 1988 and Plamondon & Alimi, 1997,

for reviews). The increase in movement time with increasing task

difficulty is accompanied by systematic changes in movement

kinematics, whether the task is executed in a discrete (Elliott, Helsen, & Chua, 2001; MacKenzie, Marteniuk, Dugas, Liske, & Eickmeier, 1987) or in a rhythmic way (Buchanan, Park, & Shea, 2004;

Buchanan, Park, & Shea, 2006; Guiard, 1993; Mottet & Bootsma,

1999; Mottet, Guiard, Ferrand, & Bootsma, 2001). In both cases,

changes in the velocity profiles are to be seen, with such profiles

becoming more and more asymmetric (with elongated deceleration phases) as task difficulty increases. While this global effect

can be attributed to the rising influence of feedback-based control

processes under the pressure of increasing accuracy demands

(Bootsma, Boulard, Fernandez, & Mottet, 2002; Buchanan et al.,

2004; Carlton, 1979, 1981; Carson, Goodman, Chua, & Elliott,

1993; Fernandez, Warren, & Bootsma, 2006), discrete and rhythmic

movements differ in important respects (Hogan & Sternad, 2007).

As argued by Guiard (1993, 1997), the particular case of repetitive movement between targets (also known as reciprocal aiming)

allows the emergence of kinematic patterns that are not possible in

the discrete case, due to the latter’s particular boundary conditions

dictating that movements must start and stop with zero velocity

and zero acceleration. Discrete movements are characterized by

their embedding within periods of non-movement (Hogan & Sternad, 2007). Therefore, in a sequence of discrete movements the

deceleration phase that leads the current movement to stop must

218

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

be clearly distinct from the subsequent re-acceleration phase

necessary for the next movement to occur. In other words, for a

movement to be discrete deceleration must drop to zero before

re-acceleration can occur (Guiard, 1993). In the case of pure

continuous movement, on the other hand, the deceleration and

re-acceleration phases are fully merged, giving rise to a sinusoidal

(i.e. harmonic) pattern of movement (Buchanan et al., 2006;

Guiard, 1993, 1997; Hogan & Sternad, 2007; Mottet & Bootsma,

1999). Thus, the kinematics of continuous movements are qualitatively different from the kinematics of discrete movements. Interestingly, in a reciprocal aiming task both patterns are observed as

extremes on a continuum (Buchanan, Park, Ryu, & Shea, 2003;

Buchanan et al., 2004, 2006; Fernandez et al., 2006; Guiard,

1993, 1997; Mottet & Bootsma, 1999; Mottet et al., 2001). Low levels of task difficulty give rise to harmonic, continuous movements

in which the deceleration and re-acceleration phases are totally

merged. As task difficulty increases, these two phases gradually

separate, eventually leading to discrete movement patterns for

the highest levels of difficulty attainable without artificial aids

(IDs P 7). Thus, the reciprocal precision aiming task offers a particularly rich window into the processes underlying perceptuo-motor

control in goal-directed action.

Mottet and Bootsma (1999) demonstrated that the kinematic

patterns associated with different levels of task difficulty could

be understood as resulting from a unique underlying dynamics,

parameterized in relation to the task difficulty at hand. The formulation of this dynamics in the form of a second-order equation of

motion with non-linear stiffness and damping terms (see Appendix) could be taken to suggest that kinematic trajectories result

from the operation of a non-linear oscillator, assembled within

the neuro-motor system. However, from another perspective, the

identification of the dynamics at the level of behaviour (i.e.,

the behavioural dynamics) can be taken to open pathways into

the underlying control processes, with information acting continuously on an agent having its own intrinsic dynamics (Fajen & Warren, 2007; Warren, 2006). In this view, the behavioural dynamics

are the result of the interaction between information and agent

dynamics and the latter type of dynamics cannot be reduced to

the former.

Apart from the classical finding that the reduction of (visual)

information leads to changes in movement time or in endpoint variability (e.g. Beggs & Howarth, 1972; Carlton, 1981; Keele, 1968;

Spijkers & Spellerberg, 1995), supplementary evidence in favour

of a primordial role of information in the control of aiming movements was found in a series of recent experiments. Mottet et al.

(2001) studied movement behaviour in several variants of Fitts’ reciprocal aiming task. The traditional variant (Fitts, 1954, Experiment 2), in which participants move a pointer between two

stationary targets, was compared with (a) a variant in which the

targets were to be moved alternately onto a stationary pointer

(as in placing one’s hat on a peg), (b) a variant in which participants bi-manually moved both the pointer and targets, and (c) a

variant in which one participant controlled the motion of the pointer and another participant controlled the motion of the targets.

Extensive analyses of the kinematics of the movements produced

revealed that, at the level of the relative motion between pointer

and targets, all variants gave rise to the same systematic changes

in the pattern of motion with increasing task difficulty. Given that

in the dyad-variant the two participants only shared the information available about the resulting motions of the pointer and targets, this result highlights the critical role of information in the

trajectory-formation process. A second line of evidence is to be

found in the experiment reported by Bootsma et al. (2002), where

visual access to the ongoing movement was experimentally

manipulated by making the pointer appear and disappear for variable durations during movement execution. For higher levels of

task difficulty participants were found to adapt their movement,

so as to make visual information available at particular instances

during the unfolding of the movement, again stressing the role of

information in the processes underlying movement generation. Finally, in a isometric version of the reciprocal aiming task, where

the displacement of the pointer was proportional to the amount

of force exerted, Billon, Bootsma, and Mottet (2000) found not only

that Fitts’ law held, but also that changes in (pointer) movement

time were accompanied by changes in (pointer) kinematics, comparable to those observed by Mottet and Bootsma (1999) and Mottet et al. (2001). Thus, the pattern of (pointer) motion and its

systematic changes with task difficulty were independent of the

particulars of the variable on which the effector system operated

(position, force, etc.), with similar forms of organization emerging

in the space where the task was defined.

In the present contribution we examine the role of information

in reciprocal aiming movements, by using an original experimental

entry into the perception–action cycle. Quite logically, the experimental study of the influences of informational variables on the

movements produced has proceeded by examining the effects of

manipulations of the information provided (e.g. Chardenon,

Montagne, Laurent, & Bootsma, 2004; Pagano & Turvey, 1995; Rieser, Pick, Ashmead, & Garing, 1995; Rushton, Harris, Lloyd, &

Wann, 1998; Rushton & Wann, 1999; Savelsbergh, Whiting, &

Bootsma, 1991; Smeets, Brenner, de Grave, & Cuijpers, 2002). Concentrating on the information provided, such studies have left

unaltered the relation between movements produced and environmental effects obtained. As the studies of Mottet et al. (2001) and

Billon et al. (2000) highlighted the importance of task space for the

organization of movement, we propose that the relation between

information and movement can also be studied by manipulating

the (normally fixed) effects of movement on the environment

(Warren, Kay, Zosh, Duchon, & Sahuc, 2001). That is, we propose

to intervene in the mapping between effector space—the space in

which the end-effector of the motor system moves—and task

space—the space in which the task is defined. It is important to

realize that these two spaces can be distinguished in all cases

where a tool of any type is used to perform an action.

In the framework of the present study the effects produced in

task space were separated from the motion in effector space by

having participants slide a stylus over the surface of a graphics tablet (effector space) so as to move a pointer-cursor back and forth

between two targets depicted on a computer screen (task space).

Introducing two different types of mapping between effector space

and task space allowed us to address the role played by task space

specific information (i.e., the spatiotemporal structure of the relation between pointer and targets) in the organisation of reciprocal

aiming behaviour. We hypothesized that the progressive change,

evoked by a progressive increase in task difficulty, from a continuous pattern of harmonic movement to a discontinuous pattern of

concatenated discrete movements (Bootsma et al., 2002; Guiard,

1993, 1997; Mottet & Bootsma, 1999; Mottet et al., 2001) emerges

under the influence of informational constraints situated at the level of task space (Billon et al., 2000; Bootsma et al., 2002; Buchanan et al., 2004, 2006; Fernandez et al., 2006; Mottet et al.,

2001). This hypothesis implies that the informational characteristics of the motion in task space should be expected to determine

the pattern of motion in effector space (Saltzman & Kelso, 1987).

We tested this hypothesis by comparing performance on a reciprocal aiming task under conditions with a linear and a nonlinear

mapping between effector and task spaces. Inspired by the results

of Mottet and Bootsma (1999), the nonlinear mapping gave rise to

a position-dependent change in gain, thereby introducing softening-spring characteristics into the pointer dynamics. Because under constant-gain (linear mapping) conditions the dynamics of

movement produced at high levels of task difficulty are typically

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

characterized by such softening-spring like behaviour (Mottet &

Bootsma, 1999), our nonlinear mapping was expected to facilitate

the task, leading to faster movement times and more continuous

movement patterns in effector space. Using the Rayleigh–Duffing

model developed by Mottet and Bootsma (1999), we quantified

the changes induced by task difficulty under the different mappings between effector and task spaces.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Thirteen students (nine men and four women) from the University of the Mediterranean voluntarily participated in the experiment. Aged between 20 and 25 years, nine of the participants

were right-handed and four were left-handed. All reported normal

or corrected to normal vision and none suffered from any known

visuo-motor impairment.

2.2. Apparatus and task

Participants were seated at a table, facing a CRT screen (Dell

M991, 1024 768 pixels resolution) positioned at eye level at a

distance of 60 cm from the head. A graphics tablet (WACOM UltraPad A3) was placed on the tabletop directly in front of them and

could be oriented to their convenience (within a range of ±15°).

Left-right sliding movements of a hand-held non-marking stylus

over the surface of the graphics tablet gave rise to left-right motion

of a cursor on the screen, controlled through a dedicated software

program developed in the laboratory, running on a Dell PC connected to the graphics tablet and the screen. The task was to move

the cursor (a red vertical line segment) back and forth between two

vertically elongated white targets displayed on the screen against a

black background as fast as possible without making more than 5%

errors on a given trial. The position of the stylus on the graphics

tablet (measurement accuracy of 0.15 mm) was sampled at a frequency of 100 Hz. The position of the cursor on the screen was

reconstructed from the stylus position data.

2.3. Procedure

The reciprocal aiming task was performed under two different

conditions of mapping between the movement of the stylus on the

graphics tablet (referred to as effector space) and the movement of

the cursor on the screen (referred to as task space). In one condition, the mapping was linear, with displacement in task space

being proportional to displacement in effector space. In order to

evoke movements in effector space of an amplitude comparable

to earlier studies (Bootsma et al., 2002; Buchanan et al., 2003,

2004, 2006; Fernandez et al., 2006: Mottet et al., 2001), under this

constant-gain condition a 17-cm movement of the stylus on the

graphics tablet corresponded to a 10-cm movement of the cursor

on the screen. In a second condition, the mapping was non-linear,

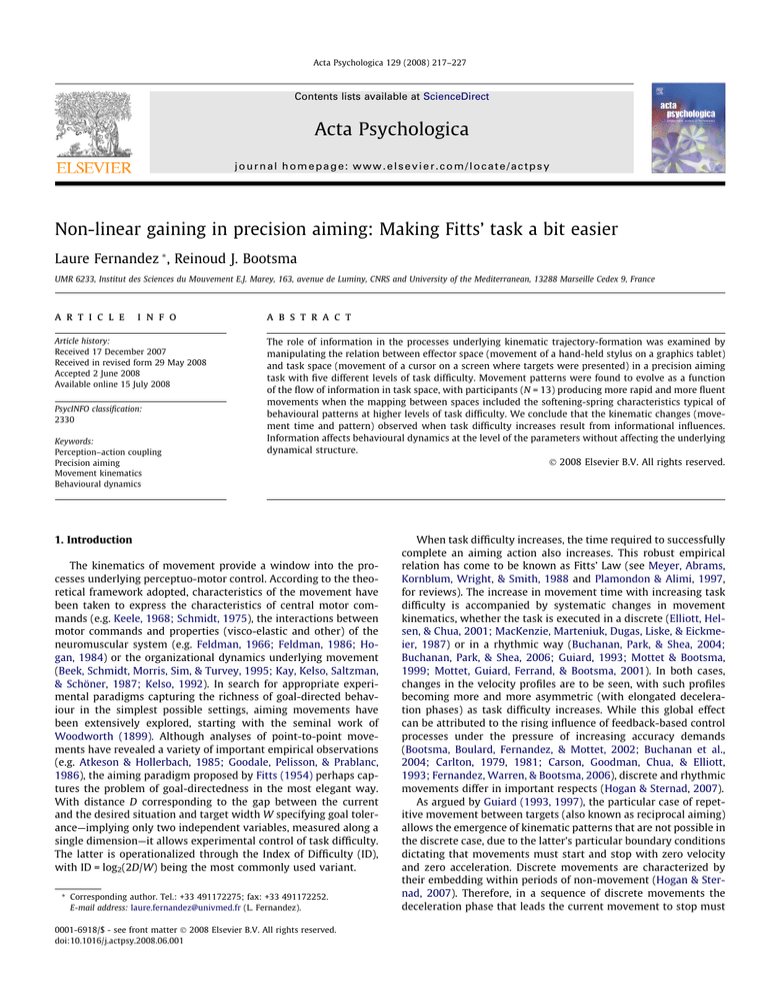

with displacement in task space following a logistic transformation of the displacement in effector space (see Fig. 1, top panel).

In the transfer function used, a purely logistic part was complemented with a linear part, in order to avoid limiting the space

reachable.

The logistic mapping implied that the gain between effector

space and task space increased in the middle part, between the targets, and decreased in the vicinity of the targets. This particular position-dependent change in gain introduces a softening-spring like

behaviour, with sinusoidal movement in effector space leading to

exaggerated velocity in the middle portion and decreased velocity

in the vicinity of the targets (see Fig. 1, bottom panel). Size con-

219

straints in effector and task space did not allow us to adapt the particulars of the logistic mapping to the characteristics of individual

participants. Therefore, the linear and logistic mappings were the

same for all participants.

For each type of mapping between effector and task space (linear and logistic), participants performed the task under five levels

of task difficulty. Following Fitts (1954; Fitts & Peterson, 1964),

task difficulty was defined through an Index of Difficulty

(ID = log2(2D/W)), where D is the distance between target centres

and W is the target width or tolerance size. In order to ensure that

participants made full use of the possibilities offered by the logistic

mapping1, we kept the distance between the inner target edges constant (at 10 cm in target space, corresponding to 17 cm in effector

space under both mappings). Thus, D varied with W according to

the values reported in Table 1.

Participants performed the 10 experimental conditions in two

blocks of five trials, with mapping conditions (linear or logistic)

varying between blocks and ID (2–6) varying within blocks. Order

of presentation was randomized. Each trial consisted of 40 cycles,

that is to say 80 aiming movements. Under each experimental condition a first trial served as practice. If participants did not succeed

in performing with less than 5% errors, another practice trial was

provided, until the criterion was met. The experimental trial was

run immediately after and the last 30 cycles (60 aiming movements) recorded were retained for analysis purposes.

2.4. Data analysis

Analyses focused on global measures such as movement time

and approximate entropy, descriptions of the kinematic patterns

produced, and coefficients of the Rayleigh–Duffing model (see

Appendix). Due to the presence of a constant-gain, under the linear

mapping conditions motion of the cursor between the targets (task

space) differed from motion of the stylus across the graphics tablet

(effector space) only by a spatial scaling factor. This was not the

case, however, under the logistic mapping conditions, due to the

presence of a position-dependent gain. We therefore separately

analyzed motion in effector space and in task space, reporting both

for reasons of completeness.

Movement time (MT) was defined as the mean half cycle time,

from one spatial movement extremum (i.e., reversal point) to the

next. By this definition, MT in effector space was perfectly equal

to MT in task space.

In order to quantify the global stability of the motion pattern,

approximate entropy (ApEn) was calculated over the full (30-cycles) position time-series of each trial. Calculation of approximate

entropy yields a single value based on a time-domain analysis of

the structure of the time-series (Pincus, 1991; Pincus & Goldberger,

1994) and is used to capture the complexity of a signal. ApEn provides an index of the predictability of the value of future events in a

time-series based on past time-series events (Slifkin & Newell,

1999). The more random the signal, the more information is required to specify future values, and the greater the associated

approximate entropy value. To situate this measure, the algorithm

used (Slifkin & Newell, 1999) returns a value of 1.65 for white

noise.

Kinematic patterns were analyzed by portraying the data in

three different ways: (a) the velocity profile, with velocity presented as a function of time, (b) the phase portrait, with velocity

presented as a function of position and (c) the Hooke portrait,

1

Pilot experiments with a constant value of D revealed that under the logistic

mapping condition with large targets participants used only a small portion of the

target, thus changing the effective amplitude of movement. By so doing, they

concomitantly reduced the effects of the logistic mapping function, as only its (quasilinear) middle part was used.

220

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

Fig. 1. (Top panel) The relation between position of the stylus on the graphics tablet (effector space) and position of the cursor on the screen (task space) under the linear and

logistic mappings. For the linear mapping y = x/1.7, where x is position in effector space and y is position in task space. For the logistic mapping y = [7.63/

(1 + exp(0.60x)] + 0.16x + 3.82. (Bottom panels) Under the logistic mapping a sinusoidal movement at the level of the effector space, characterized by a circular phase portrait

and a linear Hooke portrait, gives rise to a motion pattern characterized by a cubic (softening-spring) form in the Hooke portrait.

Table 1

Values of D (distance between target centres), W (target width) and corresponding ID

(Index of Difficulty, ID = log2(2D/W)) used in the experiment

D (cm)

W (cm)

ID (bits)

20.00

13.33

11.43

10.67

10.32

10.00

3.33

1.43

0.67

0.32

2

3

4

5

6

Values given are defined in task space.

with acceleration presented as a function of position. To keep the

velocity and acceleration scales comparable across trials without

changing portrait shape, the data were normalized as a function

of MT and amplitude (Beek & Beek, 1988). To this end, time

was rewritten in units of cycle time and amplitude in units of

D/2. In this normalized space, simple harmonic (sinusoidal) motion yields a circle of unit radius in the phase plane and a straight

line with minus unit slope in the Hooke plane. Thus, any deviation from circularity in the phase plane and from linearity in

the Hooke plane reflects non-linearity in the dynamics underlying

the movement (Mottet & Bootsma, 1999). While inspection of

these portraits allows qualitative assessment of the changes in

shape that occur over experimental conditions, the normalization

procedure provides the possibility to quantify these changes

through extraction of normalized peak acceleration (and deceleration) values. For a simple harmonic (sinusoidal) motion with its

constant phase progression these values are equal to plus (and

minus) 1. Systematic variations in phase progression thus show

up in the normalized average peak acceleration (and deceleration)

values as deviations from ±1, with larger deviations indicating

larger variations in phase progression.

The Rayleigh–Duffing (RD) model proposed by Mottet and

Bootsma (1999) was fitted to the normalized average data for each

condition using multiple linear regression procedures. Regressing

the linear and cubic position and velocity terms of the model

(see Eq. (2) in Appendix) onto acceleration provided a goodnessof-fit measure (coefficient of determinacy R2), as well as specification of each of the four model coefficients.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Movement time

A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with factors

Mapping (linear and logistic) and Task Difficulty (IDs 2, 3, 4, 5, and

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

221

Fig. 2. Movement time as a function of the Index of Difficulty under the linear and

logistic mapping conditions.

6) revealed significant main effects of Task Difficulty

(F(4, 48) = 231.01, p < .001, Effect Intensity2 EI = 75.93%) and Mapping (F(1, 12) = 194.07, p < .001, EI = 6.57%), as well as a significant

interaction between the two (F(4, 48) = 15.14, p < .001, EI = 2.54%).

Newman–Keuls post hoc analyses demonstrated that Movement

Time (MT) differed between mapping conditions, for all levels of task

difficulty except ID = 2. As can be seen from Fig. 2, under the linear

mapping condition MT increased monotonically with increasing task

difficulty, corroborating Fitts’ law once again. MT also increased with

increasing task difficulty under the logistic mapping condition, but

remained shorter for each level of task difficulty (except the lowest

level). In fact, inspection of Fig. 2 suggests that the logistic mapping

led to a shift of the MT-ID relation of approximately one bit, suggesting that this mapping made the task a bit easier.

Fig. 3. Approximate entropy as a function of the Index of Difficulty under the linear

and logistic mapping conditions in effector space (Top panel) and task space

(Bottom panel).

3.2. Approximate entropy

Due to the non-linear transformation between effector and task

space in the logistic mapping conditions, ApEn was calculated separately for the two spaces.

A repeated measures ANOVA performed on the ApEn obtained

in effector space (i.e., with respect to the motion of the stylus on

the graphics tablet) revealed significant main effects of Task Difficulty (F(4, 48) = 54.23, p < .001, EI = 60.55%) and Mapping

(F(1, 12) = 24.38, p < .001, EI = 2.95%), as well as a significant interaction between the two (F(4, 48) = 10.99, p < .001, EI = 7.81%).

Recalling that ApEn is lower for a more stable pattern, it appears

from Fig. 3 (top panel) that higher levels of task difficulty gave rise

to more stable patterns of motion. Post hoc analysis of the interaction demonstrated that under the linear mapping ApEn remained

virtually constant up to a task difficulty of ID = 4, with significant

decreases occurring for IDs 5 and 6. Under the logistic mapping

conditions, ApEn remained constant—at a value similar to ApEn

under the linear mapping conditions for IDs 2, 3 and 4—up to

ID = 5, with a significant decrease occurring at ID = 6. Again, the

two curves (linear and logistic mapping) were shifted by approximately one bit.

A repeated measures ANOVA performed on the ApEn obtained

in task space (i.e., with respect to the motion of the cursor on the

screen) revealed significant main effects of Task Difficulty

(F(4, 48) = 170.69, p < .001, EI = 74.61%) and Mapping (F(1, 12) =

38.99, p < .001, EI = 2.71%), as well as a significant interaction

between the two (F(4, 48) = 17.824, p < .001, EI = 7.21%). While

under the linear mapping conditions ApEn in task space was

identical to ApEn in effector space, the logistic transformation gave

2

Effect Intensity EI represents the percentage of total variance explained.

rise to a progressive decrease of ApEn in task space with increasing

task difficulty (Fig. 3, bottom panel). From ID = 4 onward ApEn was

significantly smaller under the logistic mapping conditions than

under the linear mapping conditions, demonstrating that the

logistic transfer function contributed to stabilizing the pattern of

movement in task space.

3.3. Kinematic patterns

Fig. 4 presents, for all experimental conditions, the velocity profiles of the average normalized cycles, with the left-to-right movements presented by positive velocities and right-to-left movement

presented by negative velocities. Figs. 5 and 6 present the same

data in the form of phase portraits (velocity vs. position) and

Hooke portraits (acceleration vs. position), respectively.

Let us first examine the linear mapping conditions. In line with

the results reported in the literature (Billon et al., 2000; Bootsma

et al., 2002; Buchanan et al., 2003, 2004, 2006; Guiard, 1993;

Mottet & Bootsma, 1999; Mottet et al., 2001), low levels of task

difficulty (IDs 2 and 3) gave rise to symmetrical, sinusoidally

shaped velocity profiles (Fig. 4, upper panels). This observation

was reinforced by the almost perfectly circular phase portraits

(Fig. 5, upper panels) and the almost perfectly linear Hooke portraits (Fig. 6, upper panels). We thus conclude that for low levels

of task difficulty the motion pattern was quasi-harmonic. When

task difficulty increased, the velocity profiles lost their symmetric

shape, with peak velocity occurring earlier on in the movement

(Bootsma, Marteniuk, MacKenzie, & Zaal, 1994; Heath, Hodges,

Chua, & Elliott, 1998; MacKenzie et al., 1987; Mottet & Bootsma,

1999). The phase portraits showed a systematic deviation from

circularity, typical of non-linear Rayleigh-type damping (see

222

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

Fig. 4. Normalized averaged velocity profiles (velocity against time) of the movements observed under the linear and logistic mapping conditions. Left-to-right movements

are represented with positive velocity and right-to-left movements with negative velocity. For the linear mapping condition, the forms in effector and task space are identical.

Scale is provided in the upper left panel.

Fig. 5. Normalized averaged phase portraits (velocity against position) of the movements observed under the linear and logistic mapping conditions. For the linear mapping

condition, the forms in effector and task space are identical. Scale is provided in the upper left panel.

Appendix for more details). The Hooke portraits demonstrated the

emergence of Duffing-type softening-spring behaviour, with stiffness (defined at each point in the portrait as the ratio of acceleration over position) decreasing in the vicinity of the targets (cf.

Mottet & Bootsma, 1999).

Under the logistic mapping condition, part of the softeningspring behaviour actively produced by the participants at the higher levels of difficulty under the linear mapping conditions of the

present experiment was provided (at the level of the task space)

by the particulars of the mapping proposed (see Fig. 1). From Figs.

4–6 (middle row panels), it is apparent that participants took

advantage of the possibilities offered by the logistic mapping between effector and task space, by maintaining a (quasi-)harmonic

pattern of motion in effector space for a larger range of IDs (IDs 2,

3, and 4 for the logistic mapping vs. IDs 2 and 3 for the linear

mapping). At ID = 5, they complemented the softening-spring

behaviour offered by the logistic mapping with a degree of non-linearity observed at ID = 4 under the linear mapping condition. In the

most difficult condition (i.e., ID = 6) participants added a considerable amount of non-linearity so as to fulfil the severe precision

requirements of the task.

At the task level, the (quasi-)harmonic movement in effector

space for IDs 2, 3, and 4, gave rise to symmetrical N-shaped Hooke

portraits, whose relative scale expressed the degree of non-linearity in phase progression (see the section on normalized peak acceleration). From ID = 5 onward, the Hooke portraits became

gradually more asymmetric, with a (relatively) rapid acceleration

followed by a (relatively) prolonged deceleration.

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

223

Fig. 6. Normalized averaged Hooke portraits (acceleration against position) of the movements observed under the linear and logistic mapping conditions. For the linear

mapping condition, the forms in effector and task space are identical. Scale is provided in the upper left panel.

3.4. Normalized peak acceleration

The peak acceleration extracted from the normalized average

cycles obtained for each participant under each experimental condition allowed quantification of the qualitative observations described in the previous section3.

An ANOVA with repeated measures performed on the motion in

effector space revealed significant main effects of Task Difficulty

(F(4, 48) = 66.62,

p < .001,

EI = 70.27%)

and

Mapping

(F(1, 12) = 42.99, p < .001, EI = 3.21%), as well as a significant interaction (F(4, 48) = 7.19, p < .001, EI = 2.06%). As can be seen from

Fig. 7 (upper panel), under the linear mapping conditions normalized peak acceleration was close to 1 for IDs 2 and 3, confirming

the (quasi-)harmonic nature of the movement patterns produced

under those conditions. From ID = 4 onwards, a monotonic increase

in normalized peak acceleration was observed for the linear mapping conditions, reflecting the rising influence of the softeningspring behaviour (Mottet & Bootsma, 1999).

Under the conditions of logistic mapping, motion in effector

space was characterized by the maintenance of a (quasi-)harmonic

pattern until task difficulty reached ID = 5 (Fig. 7, upper panel). For

IDs 5 and 6, normalized peak acceleration deviated significantly

from unity, revealing that the softening-spring characteristics provided by the logistic mapping were complemented by the participants. Note that even under those conditions, peak acceleration at

each level of task difficulty remained significantly smaller for the

logistic mapping conditions as compared to the linear mapping

conditions. Once again the two curves appear to be shifted by

approximately one bit.

A repeated measures ANOVA performed on the motion in

task space revealed significant main effects of Task Difficulty

(F(4, 48) = 30.78, p < .001, EI = 23.82%) and Mapping (F(1, 12) =

183.89, p < .001, EI = 51.95%), as well as a significant interaction

3

While the velocity profiles, phase portraits, and Hooke portraits presented were

obtained by averaging across participants at particular moments in (relative) time

(Fig. 4) or in (relative) space (Figs. 5 and 6), the normalized peak acceleration values

presented in Fig. 7 were obtained by averaging the peak values of individual

participants, extracted irrespective of time and space. Whereas the former can thus be

modulated by differences between participants, the latter cannot.

Fig. 7. Normalized peak acceleration as a function of the Index of Difficulty under

the linear and logistic mapping conditions in effector space (Top panel) and task

space (Bottom panel).

(F(4, 48) = 8.611, p < .001, EI = 3.05%). While, by definition, the

pattern of motion is the same in effector space and in task space

under the linear mapping conditions, the particulars of the logistic

mapping lead to a non-harmonic pattern of motion in task space,

even when participants produce a harmonic pattern of motion in

224

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

effector space (see Fig. 7, lower panel). Thus, for IDs 2, 3, and 4 the

harmonic patterns produced by participants in effector space (with

normalized peak accelerations close to 1) were accompanied by

non-harmonic motion patterns in task space (with normalized

peak acceleration between 4 and 8). From ID = 5 onward, the

additional softening-spring behaviour assembled by participants

further increased normalized peak acceleration.

3.5. Model fitting

The RD model adequately captured the range of behavioural

patterns observed, explaining 94% of the variance on the average.

Not surprisingly, the best fits were obtained for harmonic movements, but the model remained valid as movement became more

discrete in nature (i.e., with increasing ID). For comparison purposes, experimental and simulation data are presented in

Appendix.

Repeated measures ANOVAs on the coefficients of the RD model

revealed significant main effects of the factors Task Difficulty and

Mapping, as well as significant interactions between the two for

all four coefficients (see Table 2 for statistical details).

3.5.1. Linear (c10) and non-linear (c30) stiffness

Harmonic movement is characterized by a linear stiffness coefficient c10 close to 1 and a non-linear (cubic) stiffness coefficient c30

close to 0. In line with the observations concerning the kinematic

patterns, such harmonic movements characterized IDs 2 and 3 under the linear mapping conditions and IDs 2, 3, and 4 under the logistic mapping conditions (Fig. 8, upper panel). Increasing ID

further gave rise to an increase in both c10 and c30. Interpreted in

the framework of Eq. (2) (see Appendix), such increases in the coefficients of position-dependent conservative terms sign the coming

to the fore of softening-spring-like behaviour. With the logistic

mapping providing a qualitatively comparable non-linear position-dependent transformation (Fig. 1, upper panel), under these

conditions participants automatically obtained a degree of softening-spring-like behaviour in task space (Fig. 1, lower panels). This

allowed them to maintain a harmonic movement pattern in effector space up to ID = 4, while adding only a little non-linearity for

ID = 5. As can also be seen in Fig. 6 (middle right panel), under

the highest level of task difficulty (ID = 6) both c10 and c30 increased considerably, an effect that must be attributed to the particular characteristics of the logistic transformation used.

3.5.2. Linear (c01) and non-linear (c03) damping

When the movement in effector space is of a harmonic nature,

coefficients of the dissipative model terms (c01 and c03) are close to

zero (Fig. 8, lower panel). Although this should not be taken to imply that the movement patterns are unstable (see Appendix for

more details), the interpretation in terms of a lower degree of stability is reinforced by the results obtained on the ApEn measure

(Fig. 3). Harmonic movements were associated with a larger

approximate entropy, signing a lower pattern stability. When task

difficulty increases, initially both damping coefficients increase (for

ID = 4 under the linear mapping conditions and for ID = 5 under the

Fig. 8. Coefficients of the RD model (normalized in space and time) as a function of

the Index of Difficulty under the linear and logistic mapping conditions. Coefficients

of position-dependent (conservative) terms are presented in the upper panel and

coefficients of the velocity-dependent (dissipative) terms are presented in the lower

panel.

logistic mapping conditions). This concomitant increase in the

coefficients of dissipative terms leads to an increasing stability,

as is also revealed by a decreasing ApEn. When task difficulty further increases, even higher pattern stability is obtained by increasing c01 relative to c03. In effector space, both c01 and c03 are smaller

under the logistic mapping than under the linear mapping. As can

be seen from Fig. 3 (ApEn, upper panel), this leads to a somewhat

lower pattern stability in effector space for IDs 5 and 6. However,

due to the characteristics of the logistic transformation, the end result is a more stable pattern in task space under the logistic mapping conditions (ApEn, Fig. 3, lower panel).

Overall, the model fits reveal that the contribution of non-linear

terms increases with increasing task difficulty, albeit it to a lesser

degree under the logistic mapping conditions. Because, in the

framework of the RD model, stronger non-linearities are assimilated with slower movements, these parametric changes underlie

the changes in the pattern of movements and, ultimately the

changes in movement time.

Table 2

Summary (F and p values) of the repeated measures ANOVAs on the coefficients of the RD model for the factors ID and mapping

Main effect of ID

c10

c30

c01

c03

Main effect of mapping

F(4, 48)

p

103.95

101.53

93.86

49.17

<

<

<

<

.001

.001

.001

.001

Interaction ID mapping

F(1, 12)

p

21.55

20.23

26.08

24.79

<

<

<

<

.001

.001

.001

.001

F(4, 48)

p

5.70

5.11

8.91

12.22

<

<

<

<

.001

.005

.001

.001

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

4. General discussion

Fitts’ law states that the time required to successfully complete

an aiming action increases with the difficulty of the task, defined

by the relative precision requirements at hand. Under the conditions of a linear mapping between motion of the end-effector (stylus) on the graphics tablet and motion of the cursor on the screen

(where the task was defined), this monotonic relation between

movement time and task difficulty was found to hold once again.

The changes in movement time were accompanied by systematic

changes in the kinematics of the movements produced. At low levels of task difficulty a continuous pattern of harmonic movement

emerged. Under the influence of increasing task difficulty, this pattern progressively changed, evolving towards a discontinuous pattern of concatenated discrete movements for highest levels of task

difficulty. In line with the results of Mottet and Bootsma (1999),

the present study corroborated that these systematic changes can

be understood as resulting from parametric adaptations of an

invariant behavioural dynamics. At the level of the behavioural

dynamics, increasing task difficulty thus leads to a rising influence

of non-linear stiffness and damping components.

In the RD model (see Appendix), the stability of the oscillatory

movement pattern is primarily determined by the c01 and c03

damping coefficients. Reproducing the findings of Mottet and

Bootsma (1999), the present model fits suggested that pattern stability increased with increasing task difficulty (see Fig. 8). Because

this conclusion is to some extent dependent upon the particulars

of the damping function included in the model (see discussion in

Appendix), we also evaluated pattern stability by means of the

model-independent measure of approximate entropy (Pincus,

1991; Pincus & Goldberger, 1994). Under the linear mapping conditions ApEn was roughly constant for task difficulties up to ID = 4

and then decreased significantly with increasing ID (Fig. 3), indicating an increase in pattern stability for the higher levels of task

difficulty. The present results therefore do not confirm the inverted U-shaped relation between pattern stability and task difficulty suggested by Buchanan et al. (2004, 2006) and this issue

will need to await direct testing by means of a perturbation protocol. Nevertheless, a large body of converging evidence suggests

that a continuous, harmonic pattern of motion cannot be maintained beyond a certain, perhaps critical level of task difficulty, situated between ID 4 and 5 under standard conditions of task

execution. From there on, significant non-linearities gradually

come into play.

The increasing asymmetry of the velocity profile has attracted

quite some attention in the literature (Bullock & Grossberg, 1988;

Elliott et al., 2001). In the framework of the RD model, such

changes in the form of the velocity profile originate from a rising

influence of Rayleigh-type damping. Surprisingly, the role of the

nonlinear stiffness characteristics has been considerably less

brought out in the literature, perhaps due to the strong tendency

to concentrate on discrete movements only (Guiard, 1997). It is

important to realize that our measure of stiffness is indirect and

abstract, obtained from the ratio of (normalized) acceleration over

position. Under the assumption that mass does not change during

the movement, the Hooke portraits—where acceleration is presented as a function of position (see Fig. 5)—allow a direct assessment of the stiffness thus defined. For the lower levels of

difficulty the straight line in the Hooke portrait indicates a constant ratio of acceleration over position and, thereby, a constant

stiffness. For the higher levels of difficulty the N-shape of the

Hooke portrait indicates that stiffness is no longer constant, but

decreases from the centre outward. The logistic transfer function

used in the present experiment automatically introduced such

softening-spring behaviour into the motion of the pointer in task

space.

225

We set out to compare behaviour, at different levels of task difficulty, under conditions of linear and logistic mapping between

effector and task space in order to assess the functional role of

the softening-spring behaviour consistently observed at high levels

of task difficulty in earlier studies using a linear mapping (Bootsma

et al., 2002; Fernandez et al., 2006; Guiard, 1993; Guiard, 1997;

Mottet & Bootsma, 1999; Mottet et al., 2001). If, in a reciprocal

precision aiming task, the movement of the end-effector were

determined by the (D and W dependent) parameterization of a

non-linear oscillator assembled within the neuro-motor system,

the particulars of the mapping between effector space and task

space would not be expected to influence the pattern of movement

of the end-effector. On the other hand, if the behavioural dynamics

were to emerge from the interplay between the flow of information and the intrinsic dynamics of the agent (Mottet et al., 2001;

Warren, 2006), it should be the informational characteristics of

the motion in task space that determine the pattern of motion in

effector space. Perhaps not surprisingly, our results are consistent

with the latter interpretation that offers better possibilities for

functional adaptation to the tool used.

The particulars of the behaviour under the linear and logistic

mapping conditions reveal the rich functionality of the softeningspring behaviour. First, except for ID = 2, the logistic mapping

allowed more rapid movements for all levels of task difficulty

examined (see Fig. 2), without loss of endpoint precision. Note that

for ID = 3 the distance between the target centres is only four times

the target width. Yet, already at this (low) level of difficulty—with

an average MT of 350 ms under the linear mapping conditions—the

artificial introduction of softening-spring like behaviour was found

to lead to an increase in the overall speed of movement, yielding an

average MT of 260 ms. Second, as indicated by both the approximate entropy measure (Fig. 3, lower panel) and the coefficients

of the dissipative terms of the RD model (Fig. 8, lower panel), the

softening-spring behaviour introduced by the logistic mapping allowed a more stable pattern to emerge in task space from ID = 4

onward. This more stable pattern in task space observed with the

logistic mapping (as compared to the linear mapping) was obtained with a less stable pattern of movement in effector space.

As pattern stability is related to the flow of energy through the system, these results suggest that the logistic mapping would be more

economical in terms of energy expenditure. Third, under the logistic mapping conditions harmonic motion was maintained in effector space until a higher degree of task difficulty, as revealed by the

values of normalized peak acceleration (Fig. 7, upper panel) and

the coefficients of the conservative terms of the RD model (Fig. 8,

upper panel). Thus, the logistic mapping allowed postponing of

the gradual lengthening of the deceleration phase (see Figs. 4

and 5). Unmistakably, these results emphasize the functionality

of the softening-spring characteristics observed under standard

mapping conditions.

The comparison between linear and logistic mapping conditions

also makes it clear that the softening-spring behaviour observed at

the level of the behavioural dynamics should be understood as

resulting from the flow of information in task space (i.e., in the

space where movement has a meaning because it is there that

the task is defined). Indeed, the artefactual introduction of a degree

of softening-spring-like behaviour under the logistic mapping conditions allowed participants to produce a more efficient (i.e., certainly faster and perhaps also less energy consuming) pattern of

movement in effector space. Thus, movement produced at the level

of the effector is subordinate to the effects of this movement in the

space where the task is defined (i.e., task space). Behavioural

dynamics thus results from the interaction between the flow of

information in task space and the intrinsic dynamics of the agent

(Mottet et al., 2001; Warren, 2006; Zaal, Bootsma, & Van Wieringen, 1998). Clearly, identification of the informational variable(s)

226

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

used and defining the interaction between this information and the

intrinsic dynamics of the agent pose major challenges that need to

be addressed in future work.

Although different in important respects, it should ne noticed

that over the full distance between the two targets the two types

of mapping compared in the present study provided equivalent

mean gains (see Fig. 1). Hence, the differences evoked by the different types of mapping cannot be attributed to the mean gain value,

which is known to affect performance on Fitts-type aiming tasks to

a certain extent (Kantowitz & Elvers, 1988; MacKenzie & Riddersma, 1994).

While we continue to pursue this line of research, the results

obtained thus far already have clear practical implications. Indeed,

the logistic mapping used allowed making the task of aiming at a

target a bit easier. In the field of human–computer interaction

the adoption of desktop-based interface organizations has led to

the omnipresence of pointing actions: In order to select a document the cursor has to be placed above the icon by which it is represented. The present demonstration that the organization of

movement is a function of the flow of information in task space allows the emergence of design principles (see, for example, Blanch,

Guiard, & Beaudouin-Lafon, 2004) based on non-linear mappings

between displacement of the effector (input device) and displacement of the cursor (on the desktop). In so doing, targets can be

enlarged in effector space—thus facilitating aiming behaviour—

without occupying too much space on the already overcrowded

desktop.

The average normalized cycles represent the best possible

approximation of the limit cycle resulting from the underlying

dynamical regime, parameterized to suit the demands of the task

at hand. The particulars of the position-dependent stiffness function can be assessed without problems on the basis of these average normalized cycles. However, because energy dissipating and

energy restoring processes are in equilibrium when riding the limit

cycle, with the present method the identification of the (coefficients of the) velocity-dependent escapement function relies on

the form of the limit cycle and not on its attractive properties. As

argued above, the form of the velocity profiles, phase portraits

and Hooke portraits clearly indicates that Rayleigh damping is

predominant in the most difficult (i.e., high ID) conditions, which

is why we included this function in the model. However, it could

well be that the escapement function in fact consists of a combina_ x_ ¼ ð1 x_ 2 Þx—and

_

_ x_ ¼

tion of Rayleigh—f ðx; xÞ

Van der Pol—f ðx; xÞ

2 _

ð1 x Þx—functions whose relative contributions vary as a function of task conditions. For low IDs the movement patterns indicate

quasi-harmonic behaviour, with only a small contribution of the

stabilizing Rayleigh (or sometimes Van der Pol, see Mottet and

Bootsma, 1999) terms being detectable with the present method.

Appendix

Movement was modelled as an instantiation of a self-sustained

oscillator of the general form:

€x þ f ðx; xÞ

_ x_ þ gðxÞ ¼ 0;

ð1Þ

where the dot represents differentiation with respect to time, x the

(normalized) spatial deviation from the origin, g(x) the stiffness

function (a combination of linear and non-linear elastic processes)

_ x_ the damping function (a combination of linear and

and f ðx; xÞ

non-linear energy dissipating and energy restoring processes).

In line with the results of previous studies in reciprocal aiming

tasks (cf. Mottet and Bootsma, 1999; Mottet et al., 2001) the Hooke

portraits of the movements produced under the most difficult conditions demonstrated an N-shape. With stiffness (abstractly) defined as the ratio of acceleration over position at each point in

the (space and time normalized) portrait, such a N-shaped stiffness

can be captured by a Duffing function of the form

g(x) = (1 x2)x = x x3. The Hooke portraits of the most difficult

conditions also contained loops and intersections indicative of

asymmetries in the acceleration and deceleration phases of each

half cycle. Inspection of the velocity profiles revealed that with

increasing difficulty the velocity profile indeed became asymmetric, with the profile skewing to the right. In the phase planes,

this effect is visible as the occurrence of peak velocity in the first

and third quadrants. These deformations indicate the operation

_ x_ ¼

of a Rayleigh escapement function of the form f ðx; xÞ

ð1 x_ 2 Þx_ ¼ x_ x_ 3 Normalizing for mass, time and amplitude led

to the following equation of motion:

x_ þ c10 x c30 x3 c01 x_ þ c03 x_ 3 ¼ 0;

ð2Þ

where the coefficients are indexed following the W method notation (Beek and Beek, 1988) where cij denotes the coefficient of

xi x_ j . This model was fitted to the average normalized cycle of each

participant under each experimental condition using multiple linear

regression of acceleration onto linear and cubic position and

velocity.

Fig. A1. Observed and simulated patterns of movement under different levels of

task difficulty for the linear (A) and the logistic (B) mapping condition. Simulations

were produced using the model of Eq. (2) (Appendix) and the coefficients derived

using multiple linear regression.

L. Fernandez, R.J. Bootsma / Acta Psychologica 129 (2008) 217–227

Although according to the Approximate Entropy data (see Fig. 3)

the movement patterns are indeed less stable in low IDs than in

higher IDs, it is likely that in low IDs Rayleigh and Van der Pol functions are operating at the same time, providing sufficient stability

to the movement but with their opposing effects on the form of the

kinematic patterns cancelling out. Other methods will need to be

employed to clarify this issue.

In order to assess how well the model coefficients obtained

using the multiple linear regression of the average normalized cycle’s acceleration onto the linear and cubic position and velocity

terms characterized the movement patterns produced, we used

them to simulate the movements under different levels of task difficulty. Fig. A1 presents the observed (left column) and simulated

(right column) patterns for IDs 2, 4 and 6 in the form of Hooke portraits. Comparison between the observed and the simulated patterns indicates that the coefficient variations adequately captured

the changes in the movement patterns observed.

References

Atkeson, C. G., & Hollerbach, J. M. (1985). Kinematic features of unrestrained vertical

arm movements. Journal of Neuroscience, 5, 2318–2330.

Beek, P. J., & Beek, W. J. (1988). Tools for constructing dynamical models of rhythmic

movement. Human Movement Science, 7, 301–342.

Beek, P. J., Schmidt, R. C., Morris, A. W., Sim, M. Y., & Turvey, M. T. (1995). Linear and

nonlinear stiffness and friction in biological rhythmic movements. Biological

Cybernetics, 73, 499–507.

Beggs, W. D. A., & Howarth, C. I. (1972). The accuracy of aiming at a target: Some

further evidence for a theory of intermittent control. Acta Psychologica, 36,

171–177.

Billon, M., Bootsma, R. J., & Mottet, D. (2000). The dynamics of isometric pointing

under varying accuracy requirements. Neuroscience Letters, 286, 49–52.

Blanch, R., Guiard, Y., & Beaudouin-Lafon, M. (2004). Semantic pointing: Improving

target acquisition with control-display ratio adaptation. In Proceedings of

CHI2004, conference on human factors in computing systems, Vienna, Austria

(pp. 519–526). New York: ACM Press.

Bootsma, R. J., Boulard, M., Fernandez, L., & Mottet, D. (2002). Informational

constraints in human precision aiming. Neuroscience Letters, 333, 141–145.

Bootsma, R. J., Marteniuk, R. G., MacKenzie, C. L., & Zaal, F. T. J. M. (1994). The speedaccuracy trade-off in manual prehension: Effects of movement amplitude

object size and object width on kinematic characteristics. Experimental Brain

Research, 98, 535–541.

Buchanan, J. J., Park, J. H., Ryu, Y. U., & Shea, C. H. (2003). Discrete and cyclical units

of action in a mixed target pair aiming task. Experimental Brain Research, 150,

473–489.

Buchanan, J. J., Park, J. H., & Shea, C. H. (2004). Systematic scaling of target width

dynamics, planning, and feedback. Neuroscience Letters, 367, 317–322.

Buchanan, J. J., Park, J. H., & Shea, C. H. (2006). Target width scaling in a repetitive

aiming task switching between cyclical and discrete units of action.

Experimental Brain Research, 175, 710–725.

Bullock, D., & Grossberg, S. (1988). Neural dynamics of planned arm movements:

Emergent invariants and speed–accuracy properties during trajectory

formation. Psychological Review, 95, 49–90.

Carlton, L. G. (1979). Control processes in the production of discrete aiming

responses. Journal of Human Studies, 5, 115–124.

Carlton, L. G. (1981). Processing visual feedback information for movement control.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 7,

1019–1030.

Carson, R. G., Goodman, D., Chua, R., & Elliott, D. (1993). Asymmetries in the

regulation of visually guided aiming. Journal of Motor Behavior, 25, 21–32.

Chardenon, A., Montagne, G., Laurent, G., & Bootsma, R. J. (2004). The perceptual

control of goal-directed locomotion: A common architecture for interception

and navigation? Experimental Brain Research, 158, 100–108.

Elliott, D., Helsen, W. F., & Chua, R. (2001). A century later: Woodworth’s (1899)

two-component model of goal-directed aiming. Psychological Bulletin, 127,

342–357.

Fajen, F. R., & Warren, W. H. (2007). Behavioral dynamics of intercepting a moving

target. Experimental Brain Research, 180, 303–319.

Feldman, A. G. (1966). Functional tuning of the nervous system with control of

movement or maintenance of a steady posture: II Controllable parameters of

the muscles. Biophysics, 11, 565–578.

Feldman, A. G. (1986). Once more the equilibrium point hypothesis (model) for

motor control. Journal of Motor Behaviour, 18, 17–54.

Fernandez, L., Warren, W. H., & Bootsma, R. J. (2006). Kinematic adaptation to

sudden changes in task constraints during reciprocal aiming. Human Movement

Science, 25, 695–717.

Fitts, P. M. (1954). The information capacity of the human motor system in

controlling the amplitude of movement. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 47,

381–391.

227

Fitts, P. M., & Peterson, J. R. (1964). Information capacity of discrete motor

responses. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67, 103–112.

Goodale, M., Pelisson, D., & Prablanc, C. (1986). Large adjustments in visually guided

reaching do not depend on vision of the hand or perception of target

displacement. Nature, 320, 748–750.

Guiard, Y. (1993). On Fitts’ and Hooke’s laws Simple harmonic movement in upperlimb cyclical aiming. Acta Psychologica, 82, 139–159.

Guiard, Y. (1997). Fitts’ Law in the discrete vs cyclical paradigm. Human Movement

Science, 16, 97–131.

Heath, M., Hodges, N. J., Chua, R., & Elliott, D. (1998). On-line control of rapid aiming

movements: Unexpected target perturbations and movement kionomatières.

Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 52, 163–173.

Hogan, N. (1984). An organizing principle for a class of voluntary movements.

Journal of Neuroscience, 11, 2745–2754.

Hogan, N., & Sternad, D. (2007). On rhythmic and discrete movements: Reflections,

definitions and implications for motor control. Experimental Brain Research, 181,

13–30.

Kantowitz, B. H., & Elvers, G. C. (1988). Fitts’ law with an isometric controller:

Effects of order of control and control-display gain. Journal of Motor Behavior, 20,

53–66.

Kay, B. A., Kelso, J. A. S., Saltzman, E. L., & Schöner, G. (1987). Space–time behaviour

of single and bimanual rhythmical movements data and limit cycle model.

Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance, 13,

178–192.

Keele, S. W. (1968). Movement control in skilled motor performance. Psychological

Bulletin, 70, 387–403.

Kelso, J. A. S. (1992). Theoretical concepts and strategies for understanding

perceptual-motor skills from information capacity in closed systems to selforganization in open, nonequilibrium systems. Journal of Experimental

Psychology General, 121, 260–261.

MacKenzie, C. L., Marteniuk, R. G., Dugas, C., Liske, D., & Eickmeier, B. (1987). Threedimensional movement trajectories in Fitts’ task: Implications for control.

Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 39A, 629–647.

MacKenzie, I. S., & Riddersma, S. (1994). Effects of output display and controldisplay gain on human performance in interactive systems. Behaviour &

Information Technology, 13, 328–337.

Meyer, D. E., Abrams, R. A., Kornblum, S., Wright, C. E., & Smith, K. J. E. (1988).

Optimality in human motor performance: Ideal control of rapid aimed

movements. Psychological Review, 95, 340–370.

Mottet, D., & Bootsma, R. J. (1999). The dynamics of goal-directed rhythmical

aiming. Biological Cybernetics, 80, 235–245.

Mottet, D., Guiard, Y., Ferrand, T., & Bootsma, R. J. (2001). Two-handed performance

of a rhythmical Fitts’ task by individuals and dyads. Journal of Experimental

Psychology Human Perception and Performance, 27, 1275–1286.

Pagano, C. C., & Turvey, M. T. (1995). The inertia tensor as a basis for the perception

of limb orientation. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and

Performance, 21, 1070–1087.

Pincus, S. M. (1991). Approximate entropy as a measure of system-complexity.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 88,

2297–2301.

Pincus, S. M., & Goldberger, A. L. (1994). Physiological time-series analysis – What

does regularity quantify. American Journal of Physiology, 266, H1643–H1656.

Plamondon, R., & Alimi, A. M. (1997). Speed/accuracy trade-offs in target-directed

movements. Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 20, 279–349.

Rieser, J. J., Pick, H. L., Ashmead, D. H., & Garing, A. E. (1995). Calibration of human

locomotion and models of perceptual-motor organization. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 21, 480–497.

Rushton, S. K., Harris, J. M., Lloyd, M. R., & Wann, J. P. (1998). Guidance of

locomotion on foot uses perceived target location rather than optic flow.

Current Biology, 8, 1191–1194.

Rushton, S. K., & Wann, J. P. (1999). Weighted combination of size and disparity: A

computational model for timing a ball catch. Nature Neuroscience, 2, 186–190.

Saltzman, E. L., & Kelso, J. A. S. (1987). Skilled actions: A task-dynamic approach.

Psychological Review, 94, 84–106.

Savelsbergh, G. J. P., Whiting, H. T. A., & Bootsma, R. J. (1991). Grasping tau! Journal

of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance, 17, 315–332.

Schmidt, R. A. (1975). A schema theory of discrete motor skill learning. Psychological

Review, 82, 225–260.

Slifkin, A., & Newell, K. M. (1999). Noise, information transmission, and force

variabilité. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and

Performance, 25, 837–851.

Smeets, J. B. J., Brenner, E., de Grave, D. D. J., & Cuijpers, R. H. (2002). Illusions in

action consequences of inconsistent processing of spatial attributes.

Experimental Brain Research, 147, 135–144.

Spijkers, W., & Spellerberg, S. (1995). On-line visual control of aiming movements?

Acta Psychologica, 90, 333–348.

Warren, W. H. (2006). The dynamics of perception and action. Psychological Review,

113, 358–389.

Warren, W. H., Kay, B. A., Zosh, W. D., Duchon, A. P., & Sahuc, S. (2001). Optic flow is

used to control human walking. Nature Neuroscience, 4, 213–216.

Woodworth, R. S. (1899). The accuracy of voluntary movement. Psychological

Review, 3, 1–106.

Zaal, F. T. J. M., Bootsma, R. J., & Van Wieringen, P. C. W. (1998). Coordination in

prehension: Information-based coupling between reaching and grasping.

Experimental Brain Research, 119, 427–435.