ABSTRACT: Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most prevalent neurologic disease

advertisement

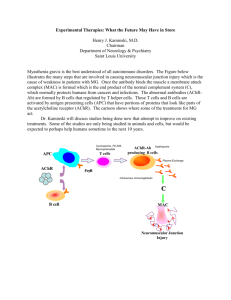

ABSTRACT: Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most prevalent neurologic disease in children and a leading cause of severe physical disability. Research and clinical experience indicate that children with CP have abnormal neuromuscular junctions (NMJs), and we present evidence that nonapposition of neuromuscular junction components is associated with the severity of motor system deficit in CP. Leg muscle biopsies collected from ambulatory (n ⫽ 21) or nonambulatory (n ⫽ 38) CP patients were stained in order to detect acetylcholine receptor (AChR) and acetylcholine esterase (AChE). Image analysis was used to calculate the extra-AChE spread (EAS) of AChR staining to estimate the amount of AChR occurring outside the functional, AChE-delimited NMJ. Nonambulatory children exhibited higher average EAS (P ⫽ 0.025) and had a greater proportion of their NMJs with significantly elevated EAS (P ⫽ 0.023) than ambulatory children. These results indicate that physical disability in children with CP is associated with structurally dysmorphic NMJs, which has important implications for the management of CP patients, especially during surgery and anesthesia. Muscle Nerve 32: 626 – 632, 2005 DYSMORPHIC NEUROMUSCULAR JUNCTIONS ASSOCIATED WITH MOTOR ABILITY IN CEREBRAL PALSY MARY C. THEROUX, MD,1,2 KARYN G. OBERMAN, BA,1,3 JUSTINE LAHAYE, MS,1,4 BOBBIE A. BOYCE,1 DAVID DUHADAWAY, BS,1 FREEMAN MILLER, MD,5 and ROBERT E. AKINS, PhD1 1 Nemours Biomedical Research, A. I. duPont Hospital for Children, 1600 Rockland Road, Wilmington, Delaware 19803, USA 2 Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, A. I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Delaware, USA 3 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware, USA 4 Physiology and Informatics Program, University of Poitiers, Poitiers, France 5 Department of Orthopaedics, A. I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Delaware, USA Accepted 25 May 2005 Previous studies suggest that children with cerebral palsy (CP) have abnormal neuromuscular junctions (NMJs). Distribution of acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) at abnormal NMJs is clinically important as the depolarization–repolarization characteristics of the muscle membrane may be affected by extrajunctional AChR. This is especially significant when neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) are used during anesthesia, as dangerous quantities of potassium may be released into the extracellular fluid.9,10,29,30 It Abbreviations: AChE, acetylcholine esterase; AChR, acetylcholine receptor; BTX, bungarotoxin; CP, cerebral palsy; EAS, extra AChE spread; GMFM, gross motor function measure; MAS, modified Ashworth score; NMBA, neuromuscular blocking agent; NMJ, neuromuscular junction; PBS, phosphatebuffered saline. Key words: acetylcholine esterase; acetylcholine receptor; gross motor function measure; hyperkalemia; neuromuscular blocking agents; spasticity Correspondence to: R. E. Akins; e-mail: rakins@nemours.org © 2005 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Published online 15 July 2005 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley. com). DOI 10.1002/mus.20401 626 Neuromuscular Junctions in CP has been shown that patients with CP have increased sensitivity to the depolarizing NMBA succinylcholine27 and increased resistance to the nondepolarizing NMBA vecuronium,11 but these results provide only indirect support for the existence of abnormal NMJs. More recently, laboratory-based assessments of NMJs in erector spinae collected from children during spinal fusion surgery gave direct evidence that children with CP have dysmorphic NMJs.28 In particular, bungarotoxin (BTX)–labeled AChR staining extended significantly beyond the functional NMJ as delimited by junctional acetylcholine esterase (AChE) immunoreactivity in CP patients, whereas AChE completely overlapped AChR staining in samples from children with idiopathic scoliosis.28 The presence of disorganized NMJs in children with nonprogressive central nervous system lesions like those found in CP is unexpected. The establishment and maintenance of NMJ organization has MUSCLE & NERVE November 2005 been well studied, and the colocalization of junctional components in NMJs is highly controlled.13,15 The nonapposition of AChR and AChE in CP therefore suggests a fundamental dysregulation of nerve– muscle interactions or a lack of NMJ maturation associated with the disease. An improved understanding of AChR localization and the organization of NMJ components in CP is needed to assure safe and adequate anesthesia, to define further the manifestations of CP, and to improve understanding of potential alterations in nerve–muscle interactions associated with disease state. Of interest in this regard is whether the nonapposition of NMJ components is functionally related to the level of motor system impairment. In this study, we examined the relationship between the degree of motor system involvement in CP and the nonapposition of AChR and AChE. We tested the hypothesis that the degree of AChR expansion beyond the limits of the functional NMJ increases with disease severity. Motor system function of CP children was estimated based on the ability to ambulate without assistance and on Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM). A digital imaging algorithm was used to quantify the degree of AChR– AChE nonapposition. MATERIALS AND METHODS Patient Selection and Sample Acquisition. We enrolled 59 CP patients in the study after obtaining institutional review board approval and signed informed consent. Signed assents were obtained where appropriate. Patients were 2–20 years of age, had spastic quadriplegic CP, and were scheduled to undergo muscle and tendon release surgery. During surgery, muscle biopsies were obtained from gracilis, vastus lateralis, or gastrocnemius, depending on the exposure of muscles during the procedure. Samples were immediately snap frozen in N2(l)-chilled isopentane. Preoperative Assessment of Patient. Prior to surgery, patients were assessed for their ability to bear their own weight in a standing position without assistance. Experienced physiotherapists performed this evaluation during a routine appointment before the day of surgery, and the results of the evaluation were collected from patient charts. Those patients that could bear their own weight were classified as ambulatory (n ⫽ 21) and those that could not were classified as nonambulatory (n ⫽ 38). Patients who did not have their ambulatory status evaluated prior to surgery were excluded from the study. In addi- Neuromuscular Junctions in CP tion, GMFM Section D scores were determined for 51 patients (15 ambulatory and 36 nonambulatory) in a separate visit to our institutional Gait Laboratory. The GMFM Section D score is a quantitative measure of motor ability associated with standing. It includes 13 separate assessments graded from 0 (no part of the task was accomplished) to 3 (the task was completed); the total score is used to assess the level of motor function. The GMFM has been validated.21,25 It is predictive of the ambulatory status of children with CP 3,20 and correlates with CP severity.19,21 Patients were also graded using the modified Ashworth scale (MAS) to estimate spasticity.2 MAS was determined for 66 muscle groups (24 ankle plantar flexion, 22 hip adduction, 10 knee extension) in 39 patients (15 ambulatory, 24 nonambulatory). The MAS ranges from 0 to 5 and was assigned by a physiotherapist based on the resistance to passive stretch within a particular muscle group. To evaluate the presence of AChRs outside functional NMJs, a previously developed double-stain method to visualize AChR and AChE was employed.28 This allowed the direct determination of AChR–AChE nonapposition within histologic sections. AChE was chosen because of its well-characterized distribution pattern and its localization to the functional NMJ.13,16,23,24 Slides containing 8-m-thick cryosections were fixed at room temperature for 5 min using 10% neutral-buffered formalin (Fisher, Fairlawn, New Jersey) and blocked at room temperature for 30 min using 3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri). Sections were rinsed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) and stained in a solution containing 0.16 g/ml tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated ␣-BTX (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon). After 1-h incubation at room temperature, the sections were rinsed with PBS and stained using a monoclonal antibody to AChE (AE-2; Biogenesis, Sansdown, New Hampshire) diluted 1:150 in PBS, followed by a fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Labs, Westchester, Pennsylvania). Samples were viewed and digitally photographed on an Olympus BX-60 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Spot RT-Slider digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, Michigan). Corrected lenses were used to minimize chromatic aberration, and the registration of fluorescence images was routinely verified using test images. The distribution of AChR relative to AChE was quantified using Image Pro software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Maryland) and a customized Histological Assessment of Samples. MUSCLE & NERVE November 2005 627 software macro. The value extra-AChE spread (EAS) was calculated as the fraction of pixels in digitized images exhibiting AChR but no AChE staining. The inter-rater reliability of the digital image analysis was determined using parallel determinations carried out by blinded research assistants. To test whether EAS was related to ambulatory status, a median value was determined for each child and ambulatory and nonambulatory groups were compared using a Mann–Whitney test. Effect size was estimated using Cohen’s d calculation: effect size ⫽ (mean difference)/(pooled SD).5 The relationship between GMFM score and EAS was evaluated using Pearson’s correlation. The relationship between MAS and EAS values was evaluated using Spearman’s correlation. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). Statistical Analysis. RESULTS Validation of Methodology and Determination of Normal Image analysis was applied to determine the area of AChR staining outside the limits of AChE immunoreactivity. As illustrated in Figure 1, staining patterns for AChR and AChE were nondiffuse and readily visualized. To validate our approach to NMJ assessment, three different investigators performed independent determinations of EAS for 100 identical NMJs from children with CP. An inter-rater reliability test yielded an alpha value of 0.8 for absolute agreement among the three measurements. Subsequent comparisons were based on values determined by a single investigator. The normal value and range of EAS were determined in control NMJs. Since all children enrolled in the current study had a primary diagnosis of CP, we used muscle samples from a previous study.28 EAS Values. FIGURE 1. Calculation of EAS values. Biopsy samples were stained for AChR and AChE. Images were digitally acquired for each label and analyzed to determine which pixels were illuminated by each fluorophore. (A) Sample images for a single NMJ from the gastrocnemius of a child with CP showing the distribution of AChR (red), AChE (green), and the combined staining. (B) Topographic representations of AChR and AChE intensities from images shown in A; distinct boundaries were easily identifiable relative to background, allowing discrimination of staining pattern edges. (C) The corresponding threshold images for AChR, AChE, and the combined information showing which pixels have AChR alone (red ⫽ 445 pixels) and which have both (yellow ⫽ 1,543 pixels). In this example, the EAS value ⫽ R/(R⫹Y) ⫽ 0.224. 628 Neuromuscular Junctions in CP MUSCLE & NERVE November 2005 was significantly lower in the erector spinae of children with idiopathic scoliosis (0.07 ⫾ 0.04; n ⫽ 26) than in children with CP (0.28 ⫾ 0.04; n ⫽ 7). Assessment of Variability between Groups. Patients in the ambulatory and nonambulatory groups were matched for age (8.1 ⫾ 5.2 and 8.2 ⫾ 4.4 years, respectively) and weight (24.7 ⫾ 14.0 and 19.7 ⫾ 9.1 kg). There were no significant differences in these parameters (P ⬎ 0.1; Student’s t-test). In addition, there was no correlation between EAS and age or weight (P ⬎ 0.8; Spearman’s correlation) for either group. Abnormal NMJs coexisted in the same histological sections as normal NMJs (Fig. 2) in both ambulatory and nonambulatory groups. Comparison of EAS values between the three muscle types collected indicated no significant difference in either patient group (P ⬎ 0.5 by Kruskal–Wallis test), and the data obtained from all muscles collected from an individual child were pooled for analysis. Descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 1. EAS differed between the ambulatory and nonambulatory groups (P ⫽ 0.025 by Mann–WhitAnalysis of NMJ Components. FIGURE 2. Nonapposed NMJs occur in the same region as apposed NMJs. Biopsy samples were stained for AChR and AChE, and images were acquired separately for each label. Images were analyzed to determine which pixels were illuminated for each label. (A) Cross section of gracilis from a child with CP showing normal and abnormal NMJ distributions in the same anatomic location and in the same histologic section. Examples of normal and abnormal NMJs are denoted by a square and a circle. (B) Higher magnification view of normal NMJ from A, showing that AChE signal overlapped the AChR signal. (C) Higher magnification view of abnormal NMJ from A, showing AChR–AChE nonapposition. Neuromuscular Junctions in CP MUSCLE & NERVE November 2005 629 Table 1. Descriptive statistics for ambulatory and nonambulatory patients.* Parameter No. of patients Mean GMFM Section D score† Mean EAS†‡ Percentage of NMJs with EAS ⬎ normal† No. of NMJs assessed No. of pixels per NMJ image† Mean EAS of NMJs in vastus§ Mean EAS of NMJs in gracilis§ Mean EAS of NMJs in gastrocnemius§ Ambulatory Nonambulatory 21 23.0 ⫾ 13.1 (15) 0.16 ⫾ 0.08 (21) 34 853 1,142 ⫾ 657 (853) 0.17 ⫾ 0.22 (45) 0.17 ⫾ 0.21 (319) 0.15 ⫾ 0.18 (489) 38 2.2 ⫾ 7.3 (36) 0.23 ⫾ 0.14 (38) 45 2,060 1,026 ⫾ 626 (2,060) 0.22 ⫾ 0.24 (352) 0.20 ⫾ 0.22 (1,120) 0.22 ⫾ 0.25 (588) EAS, extra acetylcholine esterase spread; GMFM, gross motor function measure; NMJ, neuromuscular junction. *Data presented as mean value ⫾ SD; numbers in parentheses indicate the number of determinations for each measurement. † Statistically significant comparisons (P ⬍ 0.05). Statistical comparisons between groups were carried out using parametric or nonparametric approaches as appropriate for the type of data (see text). ‡ Each child received an EAS score equivalent to the arithmetic average for all junctions assessed within that child. The mean and standard deviation of these scores are reported. § EAS values did not vary by muscle type. ney test), with nonambulatory patients having higher EAS values. The mean EAS values for ambulatory (0.16 ⫾ 0.08) and nonambulatory (0.23 ⫾ 0.14) patients were each more than two standard deviations above the mean EAS of normal NMJs (0.07 ⫾ 0.04) with the difference between groups indicating a medium effect size (d ⫽ 0.54). There was also a significant correlation (R ⫽ ⫺0.056; P ⫽ 0.005) between EAS values and GMFM Section D score. There was no correlation between EAS and MAS (R ⫽ .028; P ⫽ 0.8; n ⫽ 66). The prevalence of abnormal NMJs versus normal NMJs was also determined. On average, nonambulatory CP patients had 45% of their NMJs with EAS exceeding 2 standard deviations above normal (i.e., EAS ⬎ 0.15) compared to ambulatory patients who had 34% of their NMJs with EAS values that high. This was statistically significant (P ⫽ 0.023) by Mann–Whitney test. The post-junctional area of NMJs, as estimated by the number of pixels present in BTX-stained images, was found to be about 10% smaller in nonambulatory than ambulatory children (P ⬍ 0.001). DISCUSSION We found that differences in NMJ structure exist in CP patients such that there is a greater degree of NMJ nonapposition present in more highly affected patients. The analytical approach to estimate NMJ nonapposition was based on the detection of AChR in the absence of corresponding AChE within digitized images. This approach may underestimate true EAS since each digital image element comprised optical information from a full thickness (8 m) of the histological section examined. Thus, AChR– 630 Neuromuscular Junctions in CP AChE mismatches along the z-axis would have been overlooked. Confocal microscopy or image deconvolution may have provided more accurate estimates of EAS, but the reported approach allowed us to evaluate a much larger number of tissue sections than would have been possible otherwise. The underlying differences between ambulatory and nonambulatory patients were substantial, and significant differences were found without the application of more involved techniques. Patients with CP exhibit poor voluntary muscle control and decreased functional motor capability. These were estimated using the GMFM. GMFM Section D scores range from 0 to 39 and were considered continuous variables. Pearson’s correlation was applied to compare EAS with motor function. Although there was a strong correlation between GMFM and EAS, there was little predictive value to the relationship. GMFM scores tended to cluster into two groups (Table 1) with a large number of zero values present in the more highly affected patients. These GMFM clusters matched the independently determined values for ambulatory status. Ambulatory status was used as the principal grouping for analysis. Our results indicate an association between AChR–AChE nonapposition and the degree of voluntary motor function, with nonambulators having higher EAS values and a greater proportion of highly abnormal NMJs than ambulators. Spasticity is another characteristic feature of CP in which hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex results in increased motor neuron activity.12 Since motor neuron activity has been associated with AChR expression and NMJ size,17,31 we suspected that CPassociated differences in NMJs were related to the MUSCLE & NERVE November 2005 degree of spasticity. Surprisingly, no correlation was found between MAS and EAS, indicating that nonapposition of NMJ components may result from mechanisms that are independent of reflex muscle control. The MAS, however, does not distinguish effectively heightened stretch reflex from increased intrinsic stiffness,7 and in some cases it may not accurately indicate spasticity per se, especially in the lower extremities.1,6 Thus, although it would be intriguing to speculate that NMJ distortion in CP is associated with voluntary muscle control but independent of reflex muscle control, such a conclusion cannot be made without improved means to assess spasticity. The two groups of children in our study had different levels of mobility, and certain types of immobilization can lead to NMJ disruption. Generally, immobilization implies decreased NMJ activation due to disuse. Evidence suggests that gravitational unloading increases the average size of motor endplates in adult rats8 and that casting results in increased AChR expression.32 Other disease states associated with decreased NMJ activation, e.g., denervation, spinal cord injury, or burn, can also lead to expansion of AChR staining and upregulation of AChR subunit expression.4,9,14,18,22,29 Increased muscle impulse activity, by contrast, is associated with decreased NMJ size,17 and sustained activity inhibits ␥-AChR subunit expression in denervated muscle.31 Interestingly, because their lack of mobility is largely due to weakness, spasticity, and loss of motor control, immobilization in CP patients occurs in conjunction with continuing NMJ activation as opposed to the reduced NMJ activation commonly associated with other conditions. Consistent with this, nonambulatory (or less mobile) patients had slightly smaller NMJs, perhaps associated with greater spasticity, and in a previous study, the NMJs of CP patients appeared smaller than those of controls with no evidence for ␥-AChR expression.28 Thus, the pathways contributing to NMJ deformation in CP may be unrelated to patient mobility and distinct from those previously described for other diseases associated with disuse. Our study has implications for the management of CP patients, especially during surgery and anesthesia. The increased oral secretions and gastroesophageal reflux in children with CP26 often render the use of a rapidly acting NMBA, such as succinylcholine, attractive in securing the airway during anesthetic management. Given the NMJ abnormalities and known sensitivities of CP patients, however, anesthesiologists should exercise caution in the use of succinylcholine in patients with CP. Conversely, it is Neuromuscular Junctions in CP important to be aware of the decreased potency of nondepolarizing NMBAs in patients with disrupted NMJs because inadequate relaxation could result in procedural difficulties during surgery. Our study also suggests that treatments, therapies, and diagnostics aimed at NMJs may be of benefit to CP patients, but further elucidation of the mechanisms and pathophysiology associated with NMJ disruption and AChR–AChE nonapposition is needed. This research was presented in part to the Pediatric Academic Society, May 2004, San Francisco, California, and to the Society for Neuroscience, October 2004, San Diego, California. This work was supported in part by NAG9-1339 from the Office of Biological and Physical Research at NASA, by 1P20-RR020173-01 from the National Center for Research Resources at NIH, and by AI2003026 from the Nemours Foundation. The authors thank Kelly Quaile, Nancy Lennon, Lauren Kirstetter, Anusha Gopalrathnam, and Funbi Fagbami for their assistance with the preoperative evaluation of patients and the validation of the image analysis method. REFERENCES 1. Avery LM, Russell DJ, Raina PS, Walter SD, Rosenbaum PL. Rasch analysis of the Gross Motor Function Measure: validating the assumptions of the Rasch model to create an intervallevel measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:697–705. 2. Bohannon RW, Smith MB. Interrater reliability of a modified Ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Phys Ther 1987;67:206 – 207. 3. Boyce W, Gowland C, Rosenbaum P, Lane M, Plews N, Goldsmith C, et al. Gross motor performance measure for children with cerebral palsy: study design and preliminary findings. Can J Public Health 1992;83(Suppl 2):S34 –S40. 4. Carter JG, Sokoll MD, Gergis SD. Effect of spinal cord transection on neuromuscular function in the rat. Anesthesiology 1981;55:542–546. 5. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum; 1988. 567 p. 6. Damiano DL, Abel MF. Relation of gait analysis to gross motor function in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1996;38: 389 –396. 7. Damiano DL, Quinlivan JM, Owen BF, Payne P, Nelson KC, Abel MF. What does the Ashworth scale really measure and are instrumented measures more valid and precise? Dev Med Child Neurol 2002;44:112–118. 8. Deschenes MR, Britt AA, Gomes RR, Booth FW, Gordon SE. Recovery of neuromuscular junction morphology following 16 days of spaceflight. Synapse 2001;42:177–184. 9. Gronert GA, Theye RA. Pathophysiology of hyperkalemia induced by succinylcholine. Anesthesiology 1975;43:89 –99. 10. Gronert GA. Cardiac arrest after succinylcholine: mortality greater with rhabdomyolysis than receptor upregulation. Anesthesiology 2001;94:523–529. 11. Hepaguslar H, Ozzeybek D, Elar Z. The effect of cerebral palsy on the action of vecuronium with or without anticonvulsants. Anaesthesia 1999;54:593–596. 12. Hinderer SR, Dixon K. Physiologic and clinical monitoring of spastic hypertonia. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2001;12:733– 746. 13. Kummer TT, Misgeld T, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. Nerve-independent formation of a topologically complex postsynaptic apparatus. J Cell Biol 2004;164:1077–1087. 14. Levitt-Gilmour TA, Salpeter MM. Gradient of extrajunctional acetylcholine receptors early after denervation of mammalian muscle. J Neurosci 1986;6:1606 –1612. MUSCLE & NERVE November 2005 631 15. Lin W, Burgess RW, Dominguez B, Pfaff SL, Sanes JR, Lee KF. Distinct roles of nerve and muscle in postsynaptic differentiation of the neuromuscular synapse. Nature 2001;410:1057– 1064. 16. Lomo T, Slater CR. Control of junctional acetylcholinesterase by neural and muscular influences in the rat. J Physiol (Lond) 1980;303:191–202. 17. Lomo T. What controls the position, number, size, and distribution of neuromuscular junctions on rat muscle fibers? J Neurocytol 2003;32:835– 848. 18. Martyn JA, White DA, Gronert GA, Jaffe RS, Ward JM. Upand-down regulation of skeletal muscle acetylcholine receptors. Effects on neuromuscular blockers. Anesthesiology 1992; 76:822– 843. 19. Oeffinger DJ, Tylkowski CM, Rayens MK, Davis RF, Gorton GE III, D’Astous J, et al. Gross Motor Function Classification System and outcome tools for assessing ambulatory cerebral palsy: a multicenter study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2004;46: 311–319. 20. Ostensjo S, Carlberg EB, Vollestad NK. Motor impairments in young children with cerebral palsy: relationship to gross motor function and everyday activities. Dev Med Child Neurol 2004;46:580 –589. 21. Palisano RJ, Hanna SE, Rosenbaum PL, Russell DJ, Walter SD, Wood EP, et al. Validation of a model of gross motor function for children with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther 2000;80:974 –985. 22. Ringel SP, Bender AN, Engel WK. Extrajunctional acetylcholine receptors. Alterations in human and experimental neuromuscular diseases. Arch Neurol 1976;33:751–758. 23. Rotundo RL. Expression and localization of acetylcholinesterase at the neuromuscular junction. J Neurocytol 2003;32: 743–766. 632 Neuromuscular Junctions in CP 24. Rubin LL, Schuetze SM, Weill CL, Fischbach GD. Regulation of acetylcholinesterase appearance at neuromuscular junctions in vitro. Nature 1980;283:264 –267. 25. Russell DJ, Avery LM, Rosenbaum PL, Raina PS, Walter SD, Palisano RJ. Improved scaling of the gross motor function measure for children with cerebral palsy: evidence of reliability and validity. Phys Ther 2000;80:873– 885. 26. Spiroglou K, Xinias I, Karatzas N, Karatza E, Arsos G, Panteliadis C. Gastric emptying in children with cerebral palsy and gastroesophageal reflux. Pediatr Neurol 2004;31:177–182. 27. Theroux MC, Brandom BW, Zagnoev M, Kettrick RG, Miller F, Ponce C. Dose response of succinylcholine at the adductor pollicis of children with cerebral palsy during propofol and nitrous oxide anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1994;79:761–765. 28. Theroux MC, Akins RE, Barone C, Boyce B, Miller F, Dabney K. Neuromuscular junctions in cerebral palsy. Presence of extrajunctional acetylcholine receptors. Anesthesiology 2002; 96:330 –335. 29. Tobey RE. Paraplegia, succinylcholine and cardiac arrest. Anesthesiology 1970;32:359 –364. 30. Tobey RE, Jacobsen PM, Kahle CT, Clubb RJ, Dean MA. The serum potassium response to muscle relaxants in neural injury. Anesthesiology 1972;37:332–337. 31. Witzemann V, Brenner HR, Sakmann B. Neural factors regulate AChR subunit mRNAs at rat neuromuscular synapses. J Cell Biol 1991;114:125–141. 32. Yanez P, Martyn JA. Prolonged d-tubocurarine infusion and/or immobilization cause upregulation of acetylcholine receptors and hyperkalemia to succinylcholine in rats. Anesthesiology 1996;84:384 –391. MUSCLE & NERVE November 2005