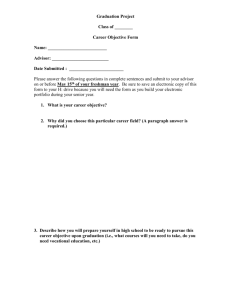

Advisor Manual

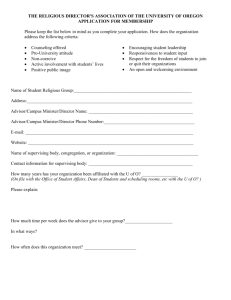

advertisement