Survivors of Trafficking from North Vietnam: Psychological and Social Consequences

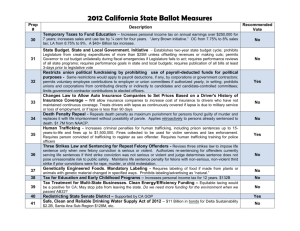

advertisement