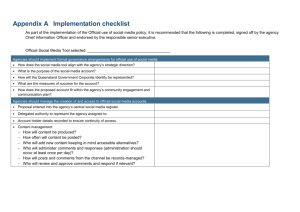

GAO

advertisement