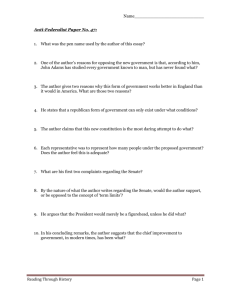

CRS Report for Congress

advertisement